How to keep smart growth affordable: build more of it

Posted October 15, 2009 at 1:00PM

One of the more frustrating challenges for people in our field to overcome is a certain past-is-destiny argument from sprawl defenders who contend that past trends in favor of large-lot, dispersed, automobile-dependent development constitute proof that Americans want more of it in the future.

In fact, signals in the market have never been clearer that consumer preferences are changing and that demand for smart growth will outpace both demand for sprawl and current smart growth supply trends in the coming decades. This is due to many factors, among them changing demographics, higher energy prices, the rebirth of central cities, the failure of the suburban model to meet many consumers' demands for convenient access to jobs and services, and a resurgence in appealing models for living in a more urban context.  Smart growth is currently constrained not so much by the market as by policy distortions and conservative lending and building practices.

Smart growth is currently constrained not so much by the market as by policy distortions and conservative lending and building practices.

This is essentially the ground that I have covered in this space for some time, perhaps summarizing it best in a post in April. But Todd Litman of the Victoria Transport Policy Institute has just done a much better and more thorough job of it, in a very well-researched, -documented, and -written paper ("Where We Want To Be: Home Location Preferences And Their Implications For Smart Growth," September 18).

Litman, who is making a career of this sort of excellent analysis, begins by examining the oft-argued myth that smart growth imposes significant costs by reducing the supply of large-lot, single-family homes that most families seek, driving up prices in the process. There might have been some truth to that hypothesis if the debate were being held three to five decades ago.  But today, the supply of large-lot housing may already be overbuilt in relation to future demand, and in any event we will need much less of it than we will need of compact, walkable neighborhoods, which are currently in significant undersupply:

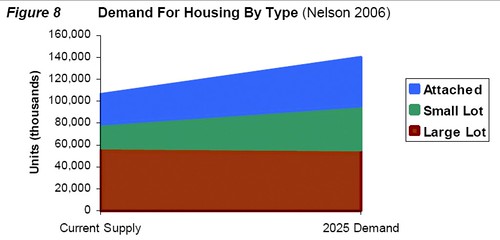

But today, the supply of large-lot housing may already be overbuilt in relation to future demand, and in any event we will need much less of it than we will need of compact, walkable neighborhoods, which are currently in significant undersupply:

"Although the exact impacts are difficult to predict and depend on how sprawl and smart growth are defined, this roughly indicates that until two decades ago (1990) more than two-thirds of households preferred sprawl housing locations and less than a third preferred smart growth, it is now about fifty-fifty, and within two more decades (2030) less than one third will prefer sprawl and more than two thirds will prefer smart growth.

"This explains why smart growth locations, such as older urban neighborhoods and new transit-oriented communities, are often unaffordable. Inadequate supply drives up prices. The rational response is to significantly increase the supply of smart growth housing to bring smart growth benefits within the budget of more consumers, particularly economically and physically disadvantaged households."

Litman argues from the evidence that during the peak of suburban optimism and urban pessimism, housing on the fringe represented a bundle of desired goods, including affordable home ownership and investment equity (particularly before condominiums became available beginning in the 1970s), larger homes and yards, separation from poverty (and minorities), perceived increased safety, superior schools, and more status. In return, consumers were willing to accept some disadvantages, including social isolation and high transportation costs (suburban traffic congestion was not yet a major factor, and the environmental and public costs of sprawl were not well known).  As a result, both the housing industry and municipal planners created a self-perpetuating cycle of automobile dependence (see illustration) that has yet to be broken, even though conditions and perceptions have changed.

As a result, both the housing industry and municipal planners created a self-perpetuating cycle of automobile dependence (see illustration) that has yet to be broken, even though conditions and perceptions have changed.

(I'll be the first to admit, by the way, that for many big cities the difference in public school quality between city and suburb remains very real. As David Owen suggested, that's now an environmental problem. But, even so, the percentage of households with school-age children is nowhere near what it was during the peak sprawl years and is likely to further decline as a portion of overall housing demand.)

Litman walks the reader through the evidence, from market surveys to trend data to quite a bit of academic research, all suggesting that, while demand for large-lot suburban homes will remain (an important point), it is not where the growth in demand will occur. Note the graph from Chris Nelson's research projecting where the growth in future demand will occur:

In this dynamic, it is no wonder that one of the frequent criticisms raised in connection with close-in, convenient, walkable neighborhoods is that they can be so expensive. Litman cites the 2001-2002 SMARTRAQ study for the proposition that, while at that time 20-40 percent of the Atlanta housing market "strongly preferred" walkable neighborhoods, only five percent of the area's housing stock was located in such areas. Heck, even in Houston, when survey respondents were asked whether they would prefer to live "in a suburban setting with larger lots and houses and a longer drive to work and most other places" or "in a more central urban setting with smaller homes on smaller lots, and be able to take transit or walk to work and other places," fifty-five percent chose the more urban option. Smart growth is only going to become less and less affordable unless we build more of it.

Litman closes the paper with a point-by-point analysis of smart growth criticisms and policy arguments. Overall the analysis is a fabulous summary of the issues and evidence and includes a lengthy, detailed bibliography. Highly recommended.