Arts-driven revitalization in Kentucky - yes, Kentucky

Posted December 17, 2010 at 1:28PM

To creative-class types who inhabit trendy east and west coast cities and a few mid-country oases like Austin and Boulder, sleepy Paducah, Kentucky (population estimated 25,720 in 2009) might seem an unlikely location for a major revitalization effort being driven by artists. But even irony-laden urbanites would be soon impressed by what is becoming a national model for “creative placemaking,” to borrow a phrase from the National Endowment for the Arts and The Mayors’ Institute on Community Design.

Paducah was founded at the confluence of the Tennessee and Ohio Rivers in the early nineteenth century. It prospered in the 1950s, partially as a result of being selected as a site for a uranium enrichment plant by the US Atomic Energy Commission. But harder times followed, and the small city’s population has declined by about a quarter since its peak in 1960. According to its Wikipedia entry, 22 percent of Paducah’s population was living below the poverty line as of 2000, including 34 percent of those under age 18. Those numbers have surely worsened since the recession hit.

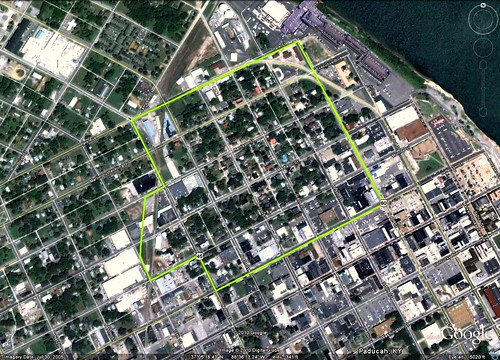

The city’s LowerTown district, with tremendous historic building stock (20 blocks in central Paducah are listed in the National Register of Historic Places), had become victim to severe disinvestment. The story is recounted in a recent report (Creative Placemaking, a white paper available here) commissioned by The Mayors’ Institute:

“Ten years ago most residents wouldn’t even drive through LowerTown, a neighborhood four blocks from downtown and the Ohio river. Over 60% owned by absentee landlords, LowerTown’s historic building stock had fallen into severe disrepair. Few townspeople wanted to invest in properties that could cost $200,000 to fix up, because the renovated homes would sell for only $80,000.”

(This post draws heavily from the report.)

Photos eloquently convey the assets the district has had to build upon, though:

The turnaround was the brainchild of artist Mark Barone. Having rehabilitated two homes in LowerTown, Barone saw how its large spaces could accommodate artist live/work set-ups. In 1999, according to the Mayor’s Institute report, he envisioned the neighborhood’s potential as an artist district. The idea caught the attention of Paducah mayor Albert Jones, who drafted Barone to coordinate a pioneering “artist relocation program.”

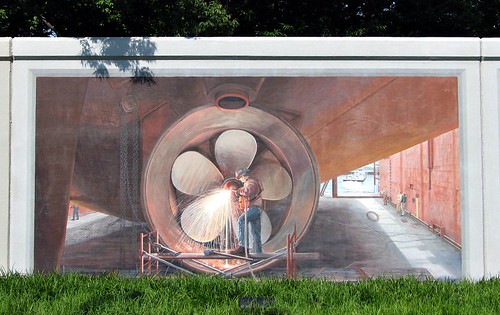

The idea built upon some art-related assets already in Paducah, including the National Quilt Museum and a remarkable and extensive set of murals installed on the city’s flood wall (Paducah experienced severe flooding in 1937). Begun in 1996 by Louisiana mural artist Robert Dafford, the over 50 WPA-inspired murals cover a number of subjects, “including Native American history, industries such as river barges and hospitals, local African-American heritage, the old Carnegie Library on Broadway St., steamboats, and local labor unions” (see photos). Both the Museum and the flood wall are just outside the LowerTown boundary.

Recognizing the long-term value of an improved central Paducah, a local bank offered attractive financing arrangements for artists interested in coming to LowerTown. The city extended $2,500 per artist to subsidize the cost of professional fees and architectural services and turned over property titles for as little as a dollar. The bank then matched program-qualifying artists with low-interest loans, starting with a modest $370,000 loan for a demonstration project that renovated three storefront buildings. The bank expanded its lending to $2 million within the program’s first year.

Under the program, now ten years old, artists apply to acquire and rehab city-owned properties, preparing cost and time estimates for rehabilitation and business plans. Those who qualify rehabilitate their properties, many setting up studios or galleries on the ground floor and living space above.  As owners, artists then earn equity on the properties.

As owners, artists then earn equity on the properties.

To support the revitalization, Paducah’s planning department changed the city’s zoning ordinances to permit both residential and commercial uses. The city also designated LowerTown as a historic district and required that renovations follow design guidelines. By collecting on liens, and through auction and foreclosure, the city increased its efforts to acquire neglected properties that could then be made available to program applicants. To discourage predatory landlord practices, the city enforced health and safety codes. With transportation enhancement grants (available under a great federal transportation program) totaling $3 million, the city also invested in comprehensive lighting and sidewalk improvements for LowerTown.

The Mayors’ Institute report recounts the success:

“With only modest public sector outlays, the city leveraged a 10-to-1 return on public investment, thanks to Paducah bank’s unusual risk tolerance for artists. Within 25 square blocks, 70 artists rehabilitated 80 LowerTown properties and constructed 20 new buildings. Long-time residents who once avoided LowerTown now buy homes there, start small businesses, and patronize artists. Even in a sour real estate climate, renovated LowerTown homes now sell for a competitive $250,000 or more.

Eleven different awards programs [KB note: including the American Planning Association] have recognized Paducah as a national standout.”

The report candidly describes some of the program’s challenges, including some community opposition and the displacement of some low-income renters (which the city mitigated by increasing its inventory of available affordable units), as well as the need to sustain the gains catalyzed by the program in the long run. But what a great beginning.

The primary caretaker of the revitalization is the Paducah Renaissance Alliance, which is supported through charitable contributions from private citizens, businesses, and other civic organizations who desire to see LowerTown continue to thrive as an historic district, and premier arts and entertainment attraction. The city also provides support to the organization through funding and various city support services. PRA undertakes activities in economic development and assistance, community promotion, organization, and design. For example:

“Design means getting the Renaissance Area into top physical shape. Capitalizing on its best assets such as historic buildings and pedestrian-oriented streets is just part of the story. An inviting atmosphere, created through attractive window displays, parking areas, building improvements, street furniture, signs, sidewalks, street lights, and landscaping, conveys a positive visual message about the Renaissance Area and what it has to offer.

Design activities also include instilling good maintenance practices in the Renaissance Area, enhancing the physical appearance of the commercial district by rehabilitating historic buildings, encouraging appropriate new construction, developing sensitive design management systems, and long term planning.”

In addition, PRA coordinates fundraising events including an annual membership drive, Old Market Days, commemorative brick sales, vending space at the Downtown Farmer's Market, Wall to Wall Mural merchandise sales and various other events held throughout the year.

I've had the opportunity in the past to write about arts-driven community development (in Houston and Los Angeles), and I remain impressed by the possibilities and by the vision of the artists behind them. In Paducah, as elsewhere, none of this was undertaken for environmental reasons, or because of anything having to do with smart growth. But we need healthy towns and cities for sustainability, and in-town revitalization displaces sprawl, attracting more investment inward, saving land and resources.

It also, not incidentally, improves lives. In fact, I would say that the generation of environmental benefits through indirect pathways is even better in some ways than a more direct approach, because those pathways are supported by additional constituencies. I’m often asked about how our principles can be applied in smaller communities, and now I have another great example.

Move your cursor over the images for credit information.