A strong case for a rail- and transit-oriented California

Posted January 9, 2012 at 1:29PM

Imagine a scenario by which our country’s most populous state, notorious for freeways, traffic nightmares and smog, could reduce driving by 3.7 trillion miles by 2050 (compared to trends forecast under business as usual), the equivalent of taking all cars off the state’s roads for 12 years. Imagine saving 140 billion gallons of gasoline through 2050, reducing oil consumption by an amount roughly equivalent to seven years’ worth of all US offshore oil production. Imagine saving some 3,700 square miles of California farmland, forests, recreation areas, and other currently open space that would otherwise be lost to sprawl. Imagine eliminating 140 premature deaths and 105,000 asthma attacks and respiratory symptoms each year.

Those were among the findings reported in 2010 by Vision California, a scenario planning exercise that compared alternate strategies for accommodating an additional 60 million people and 24 million jobs expected to be absorbed into the Golden State by 2050. Funded by the California High Speed Rail Authority in partnership with the state’s Strategic Growth Council (a cabinet-level, statutorily mandated committee), the exercise was led by the highly respected urban design and planning firm, Calthorpe Associates.

The envisioned benefits would come from a “growing smart” scenario that would leverage the construction of a planned high-speed rail network with smart land use around and near the network's stations and additional intra-city transit systems. The scenario would include a more balanced housing mix, more infill development, and greater transportation options than under a business-as-usual scenario, which assumes a continuation of dispersed, auto-oriented development patterns (albeit with continued modest improvements in automobile, building, and energy generation efficiency). Even greater comparative benefits would be realized under a more ambitious “green future” alternative.

Peter Calthorpe, the charismatic California-based architect who founded Calthorpe Associates and has supervised large-scale planning exercises all over the US and a number of other countries, has come to believe that high-speed rail is a major key to achieving a more benign future for his home state. Writing last week in The San Francisco Chronicle, Calthorpe makes the case:

“Today, our country desperately needs new infrastructure development that will create jobs and economic growth while updating the American Dream and ensuring its environmental future. The answer is high-speed rail.

“More than a train ride is at stake; high-speed rail could catalyze the next generation of growth - one more oriented to who we are, what we can afford and what we really need. High-speed rail, along with innovative land use, will breed the kind of economic development and communities California is missing most - urban revitalization along with more walkable, affordable communities.

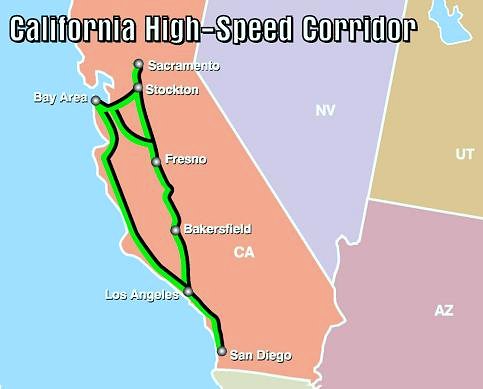

“California's 520-mile-long high-speed rail would connect north and south for half the dollars that otherwise would be needed for highway expansion and new airport facilities. More significantly, it would become a catalyst for urban renewal, enhance local transit systems and generate market-wise development opportunities.”

International travelers marvel at the advanced, comfortable, fast, highly convenient rail systems enjoyed routinely by citizens of such countries as Japan, France, Spain, Italy, Taiwan and now the rest of China. Heck, even the Tour de France has used that nation’s famous TGV - the world's fastest passenger train - to speed its riders from Avignon to Paris. Why not the United States?

While rail can’t reasonably be expected to compete with air travel for thousand-mile-plus trips, we have plenty of regions where 100- to 500-mile trips are frequent, and where station-to-station service would be far more convenient (not to mention less stressful) than airport-to-airport. Since the inauguration of the Acela Express service between DC and New York - a modern, comfortable hourly train that is fast by US standards if still slow by international standards - I never fly the 225 miles to New York anymore. It is much easier to do work or relax on the Acela than in the cramped seats and highly regulated environment of economy air service, and you just can’t beat being able to walk to your hotel and/or meeting at the destination.

The advantages for intercity travel aside, Calthorpe likes high-speed rail as a catalyst for a broader adaptation of transit-oriented development and smarter land use. Among the additional benefits to the state:

- New highway construction could be reduced by 4,700 miles, saving the state about $400 billion.

- The availability of alternatives to driving would reduce demand for new roads and parking lots, thus also reducing the amount of stormwater runoff to be cleaned and stored.

- Less driving would mean less air pollution and associated respiratory diseases. More walking in walkable neighborhoods built around transit would mean healthier bodies and less obesity, reducing health costs.

- Smaller parking lots and less demand for large-lot homes would reduce the need for irrigated landscaping, saving enough water per year to irrigate 5 million acres of California farmland.

- The cost of maintaining and fueling autos would go down, saving California households close to $11,000 in current dollars per year.

Read his entire article here.

Calthorpe, who has been an influence and become a professional friend in my own career, has had a major role in developing the design principles underlying what we now understand, partly due to his work, as “transit-oriented development” – walkable, mixed use neighborhoods built around transit stations. (See Oakland's Fruitvale Village, above.) The concept is now widely espoused in planning departments across the country, for all of the reasons highlighted in the data above. While the empirical evidence suggests that TOD does not eliminate car use – and why would we expect it to? – there is now little question that it reduces both the number and length of car trips.

The older DC suburb of Arlington, Virginia, for example, was one of the first jurisdictions in the country to undertake planned transit-oriented development at a large scale, along the Orange Line corridor of the DC region’s Metro rail transit system. By concentrating growth through redevelopment of mostly outdated commercial property along the corridor, Arlington added 17 million square feet of office space and 24,000 homes with almost no increase in automobile traffic. Meanwhile, Arlington’s substantial inventory of lovely single-family homes remains undisturbed by the redevelopment.

The DC region was also one of four metros (the others were Philadelphia, Portland, and the San Francisco Bay Area) included in a study of 17 TODs by the well-known planning and engineering firm PB Placemaking; that research found that, on average, the TODs reduced car trips by 49 percent in the morning peak period and 48 percent in the evening peak, compared to what would be expected from standard engineering estimates typically used by municipalities.

The benefits of TOD come not just from the proximity to transit but also from the mixed-use, walkable neighborhood design used in conjunction with transit. For example, the award-winning suburban TOD Orenco Station, at the terminus of one of the Portland region’s light rail lines, has been the subject of additional research. While residents of Orenco Station continue to use cars for many of their trips, 50 percent report walking to a store or shop five or more times a week; that is ten times the rate reported in an otherwise comparable suburban neighborhood with poor street connectivity and limited walkable access to shops and amenities.

In addition, 67 percent of Orenco residents say they use mass transit at least once a week; the other neighborhood is also within a quarter-mile of a light rail station, but only 42 percent of its residents report using transit. In other words, walkability matters, too: “transit-oriented development” requires not just transit but proper orientation to the transit. Orenco’s 15 percent share of transit use for commuting has been criticized by some as being disappointingly low, but it is nonetheless three times the national median. I haven’t seen reports of driving rates for Orenco (best measured as annual vehicle miles traveled per capita), but my guess is that the amount of walking trips and shorter driving distances enabled by its neighborhood-based shops and services, plus its more frequent transit usage, would produce notably lower rates of driving compared to non-TOD suburban neighborhoods, if perhaps still higher than an inner-city TOD would.

All this in addition to saving land, water, and public expenditures while reducing pollution and illness. Given that, according to Calthorpe, expanding highways and airports to accommodate California’s growing population would likely cost some $171 billion, the case for using some of that money instead to invest in high-speed rail appears strong. Calthorpe’s article says that the California Legislature needs to authorize $2.7 billion in bonds (plus $3.5 billion in matching federal funds) to begin the project.

Move your cursor over the images for credit information.