Will the real green colleges please stand up? (by Lee Epstein)

Posted March 21, 2012 at 1:29PM

Today’s post is guest-authored by my friend and frequent collaborator, Lee Epstein. Lee is an attorney and land use planner working for sustainability in the mid-Atlantic region.

In the middle part of the past decade, “sustainability” became somewhat of a “college craze” – that is, for ever-competitive college administrators. Lots of schools jumped on the “green” bandwagon, though some had already been leading the parade for some time. Others, sadly, have yet to see the light.

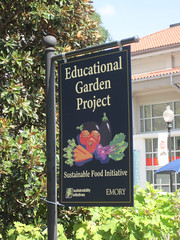

Oberlin College committed early on to sophisticated sustainable buildings, and local and organic food. My own alma mater, Dickinson College, embraced sustainability as one of the defining measures of both campus systems (LEED Gold buildings, waste oil for biodiesel transportation and for its boilers, its own organic farm supplying its foodservices, free bikes) and its academic and curricular focus. The University of Colorado at Boulder has committed that all of its new buildings will meet commendable LEED Gold standards, and it runs an alternative transportation system.  UCLA recycles, recycles, and then recycles again. The University of New Hampshire fires up landfill gas to supply energy on campus. Arizona State University has a School of Sustainability. American University buys tens of millions of kwH of wind energy and has thoroughly greened its campus. And Middlebury College runs a biomass gasification plant to help it attain carbon neutrality by 2016.

UCLA recycles, recycles, and then recycles again. The University of New Hampshire fires up landfill gas to supply energy on campus. Arizona State University has a School of Sustainability. American University buys tens of millions of kwH of wind energy and has thoroughly greened its campus. And Middlebury College runs a biomass gasification plant to help it attain carbon neutrality by 2016.

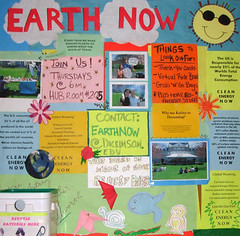

(Previous articles on this blog have described Emory University’s impressive commitment to sustainability and William and Mary’s new eco-village.)

Measuring a green college or university

There are many ways to measure how green a college is, and there are now very public pronouncements on who’s made it to the “top x number” of such schools: the Sierra Club has an annual list and Grist magazine keeps one. There’s a “College Sustainability Report Card,” and a slew of college presidents have signed on to a climate change pledge. Most recently, the Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education (AASHE) has created a master Sustainability Tracking, Assessment, and Ranking System (STARS) that will feed its information to the Princeton Review and other publications. Of course, the easiest measure is still the most visible one: is the college constructing its new buildings or rehabilitating its old ones to high sustainability standards, such as LEED-NC (New Construction) Silver, Gold or Platinum levels? Is it re-designing its landscapes with native plants, and substantially reducing its rainwater runoff with techniques that allow infiltration, plant uptake, and the re-use of stormwater?

Another measure is the extent to which the college or university integrates with its surrounding community, to the extent there is one. This is the college equivalent of LEED-ND (LEED for Neighborhood Development): to the extent possible, is there continuity and sufficient connectivity with the streets and services beyond the campus; is the campus and are those connections with the municipality walkable; does the campus provide good access, without having to drive, to multiple destinations, such as food and necessities, entertainment, recreation, or health care?

Another measure is the extent to which the college or university integrates with its surrounding community, to the extent there is one. This is the college equivalent of LEED-ND (LEED for Neighborhood Development): to the extent possible, is there continuity and sufficient connectivity with the streets and services beyond the campus; is the campus and are those connections with the municipality walkable; does the campus provide good access, without having to drive, to multiple destinations, such as food and necessities, entertainment, recreation, or health care?

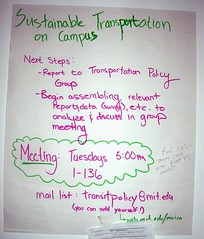

A third measure is whether the internal workings of the physical plant have been “greened”: have water systems been made efficient and is gray water re-used; what kind of energy is used to heat and cool buildings; are transportation systems green, efficient, and readily available; how do food services operate, are foods locally sourced, are various wastes recycled or composted, and has waste been minimized overall; and finally, what about campus wastes as a whole – is there an effective recycling system, is paper re-used, are record systems electronic? These physical plant practices have real, calculable efficiency cost returns.

The environment in the curriculum

Finally, and I would argue, most crucially but least well incorporated, does the university embrace sustainability throughout its curriculum? The purpose of a college or university is to t each. All of the above actions can help serve that function to one degree or other as daily examples to students, faculty, and the surrounding community. But most centrally, if the college fails to integrate sustainability into its course offerings – and not just in the physical sciences or in an “environmental studies” department but in philosophy, history, political science, business, and the like – it cannot attain its green potential as an institution of the highest learning. I should note that this is not a matter of teaching to a liberal or conservative agenda; sustainability should transcend political labels.

each. All of the above actions can help serve that function to one degree or other as daily examples to students, faculty, and the surrounding community. But most centrally, if the college fails to integrate sustainability into its course offerings – and not just in the physical sciences or in an “environmental studies” department but in philosophy, history, political science, business, and the like – it cannot attain its green potential as an institution of the highest learning. I should note that this is not a matter of teaching to a liberal or conservative agenda; sustainability should transcend political labels.

There are some schools that are coming late to the party, some that are making the barest of green gestures (mostly for green-washing purposes), and way too many that frankly haven’t a clue or couldn’t care less. They may say that’s because of tight, tough budgets, but as noted above, that’s not a valid excuse. Or they may say that’s just because it’s not who we are: we are an (fill in the blank): agricultural school, and pretty much only about agronomy, agricultural economics, and crop sciences; big public university, so we’ve got to provide the broadest of academic programs and the state legislature wouldn’t stand for this “green” stuff, anyway; small private college, so we haven’t the resources to devote to this; school with an international reputation in the sciences (or social sciences, or…), and sustainability is a niche subject in which we can only offer a course or two; a religiously-based institution, and everything we do must reflect that singular focus.

The funny thing is, every one of these arguments is merely an excuse, the effect of short-sightedness or dismissive thinking. The agricultural school could surely find a way to integrate the idea of green food systems into its curriculum, and maybe even into its own cafeterias. The small, private college could, with some very modest investigation, come to understand that gradually investing in a green campus could save it money over a fairly short time horizon. The big, public university could also realize significant capital returns on investment, which might buy it favor with the legislature while it begins to broaden its sustainability-related curricular offerings. And my goodness, the religious-based institution could find no better ethical model than that which is the ecological equivalent to the “golden rule.”

The funny thing is, every one of these arguments is merely an excuse, the effect of short-sightedness or dismissive thinking. The agricultural school could surely find a way to integrate the idea of green food systems into its curriculum, and maybe even into its own cafeterias. The small, private college could, with some very modest investigation, come to understand that gradually investing in a green campus could save it money over a fairly short time horizon. The big, public university could also realize significant capital returns on investment, which might buy it favor with the legislature while it begins to broaden its sustainability-related curricular offerings. And my goodness, the religious-based institution could find no better ethical model than that which is the ecological equivalent to the “golden rule.”

An environmental moral compass

The bottom line is this. While it’s better than nothing, a building or two does not a college or university make. These are public and private institutions where our future as a nation, and to some extent even as a world, is being shaped with every student who matriculates (there are currently some 20 million students in U.S. post-secondary education). If that future world is to fully embrace the idea of sustainability – by that I mean the  broadest principle of making sure our actions today do not lessen our health and the earth’s survivability tomorrow – and by all accounts it must, then our systems of higher education must fully and adequately embrace this idea. They must build their buildings to it, design and operate their campuses by it, shape their curricula with it in mind, and provide the equivalent of an environmental moral compass for the millions of students in their short-timed pedagogical care.

broadest principle of making sure our actions today do not lessen our health and the earth’s survivability tomorrow – and by all accounts it must, then our systems of higher education must fully and adequately embrace this idea. They must build their buildings to it, design and operate their campuses by it, shape their curricula with it in mind, and provide the equivalent of an environmental moral compass for the millions of students in their short-timed pedagogical care.

Education is about the only way we are going to get out of the ecological mess we’re in. It’s up to our much-vaunted institutions of higher learning to lead the way, and we should insist – with our tuition checks and our citizen oversight of the public institutions – that they finally begin a green century of building and learning and teaching.

Other recent posts by Lee Epstein:

- Let's link the working rural landscape to the sustainability agenda (with Lee Epstein) (March 1, 2012)

- How a rain garden cleans industrial pollution (January 25, 2012)

Move your cursor over the images for credit information.

Please also visit NRDC’s Sustainable Communities Video Channel.