How creative entrepreneurs are enlivening Miami's Little Havana

Posted September 14, 2012 at 1:35PM

I think something special may be happening in Little Havana, the neighborhood that serves as the social and cultural heart of Miami’s Cuban-American community. I am far from a local when it comes to things Floridian, but I have a cluster of good friends in Miami, most of them involved in the worlds of community thinking and design. Not long ago, Little Havana started coming up repeatedly in their conversations. I decided to do some research, and now I see what the buzz is about.

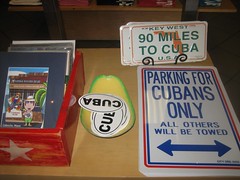

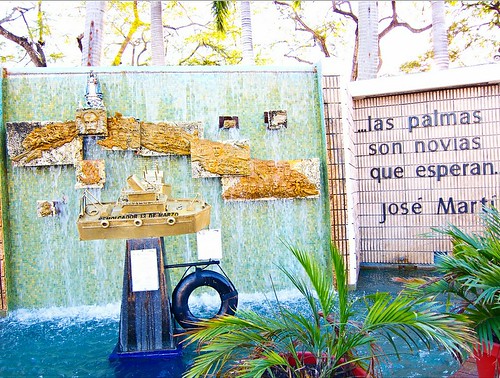

A loosely defined district covering around three square miles just west of downtown Miami and housing some 50,000 residents, the neighborhood has a strong and proud Hispanic identity, reinforced by its visible components. There’s a monthly arts and culture festival; one of the largest annual celebrations of Carnival in the world, along Calle Ocho (8th Street, the area’s main drag); many small ethnic businesses; a wealth of historic properties and markers; and the Miami Marlins’ baseball stadium, where the famous Orange Bowl used to be.

Indeed, LittleHavanaGuide.com lists a dozen important neighborhood assets, including architecture, art, baseball, botanicas (shops carrying traditional spiritual and religious products), cigar factories and stores, cuisine, legendary games of dominoes, festivals, a central location, music and dance, affordability, and theater and film. The community is overwhelmingly Hispanic, now including residents whose families derive from Central America as well as those linked to Cuba. It contains some of the oldest and most historic buildings in Miami, including many fine examples of classic bungalow architecture. It is, in short, a place brimming with what, for lack of a better word, we call “character.”

But there are good reasons to remain attentive to the rich cultural ingredients that make Little Havana special. In the 1980s, like so many inner-city neighborhoods in America, Little Havana was plagued by neglect, crime, drugs, and decay. While its physical character is historic and its culture has been strong for at least the last fifty years, in some ways the neighborhood's re-emergence is new and complicated by uncertainties.

In particular, about a decade ago, the National Trust for Historic Preservation charged that Miami has “a weak preservation ethic” that has allowed historic resources to be demolished across the city. The Trust noted that Little Havana had so far retained many of its historic residences, including bungalows and small apartment buildings, but also that much of the neighborhood's housing stock is owned by absentee landlords with little interest in rehabilitating aging properties. The zoning in effect at the time, according to the report, encouraged high-density and large-scale development rather than a more sensitive approach.

The Trust expressed hope that the form-based zoning code that was then being discussed for the city (and was adopted about three years ago) would give developers a stable set of rules that could encourage the right kind of investment in the city’s historic neighborhoods. But another issue identified by the report was that, among many immigrants, Little Havana was seen as a point of entry into American life but also a place to escape as one makes progress. Neighborhood pride was seen as fragile.

Today, though, some very interesting developments, supported by energetic neighborhood champions and entrepreneurs, suggest that things are looking up for the district’s future. One can hardly do any kind of research on the neighborhood, for example, without running into multiple references to Corinna Moebius, co-founder of the Little Havana Merchants Alliance, board member of the Urban Environment League, and founder and editor of a growing online guide and magazine serving the neighborhood, LittleHavanaGuide.com. The site, like its neighborhood, is colorful and lively, full of articles about Little Havana’s arts, culture, businesses, and goings-on. Drum-making, graffiti art, ice cream and midwifery were among the subjects highlighted when I looked at the site yesterday.

But it’s also serious. Earlier this year the site published a letter from Bill Fuller, businessman and co-founder of the Merchants Alliance, warning of the intrusion of big-box stores that do not respect the neighborhood’s character:

“Without any historical designations or design review processes within the neighborhood, we are left at the mercy of traditional, 'off-the-shelf' store designs that push our urban oasis closer to surburbia than ever before. Drive-thrus, large signage and demolition of historical buildings [are] all part of their plan to convert Calle Ocho from its current status as a historical and cultural mecca to just another big-box non-descript version of Miami street.”

With Moebius, Fuller has set up a watchdog website called LittleHavanaInc.com, “monitoring the recklessness of corporate America in Little Havana.” While the site slams chains such as AutoZone and McDonald’s for being particularly insensitive, it also shows balance by praising Walgreen’s for preserving a 1920s building and setting “an excellent example of how you can build new business and preserve the past.”

Moebius’s LittleHavanaGuide has a number of articles devoted to placemaking, including a very encouraging story about the pending renovation of the historic Tower Hotel, which in its roughly century-long history has served as a hospital, veterans’ retirement facility, and pied-a-terre for African-American jazz musicians who had to be sneaked in during the days of segregation. (The Tower, still operating as a hotel, is now owned and being updated by Fuller’s development firm. Fuller is also rehabbing a nearby property “into a multipurpose facility for art shows, meetings and events.”)

I also need to mention Pablo Canton, administrator of the Little Havana Neighborhood Enhancement Team, who was praised in the National Trust’s report for supporting new businesses and the monthly festival. While Canton has done much behind the scenes, one of his most visible accomplishments was the placement of highly decorated rooster sculptures around the district,  adding color and celebrating local identity. This led to a local news story last year when one of the 70-pound fiberglass statues, owned by Canton himself and painted with a hybrid Cuban/American flag motif, was stolen as part of a college prank before being remorsefully returned, and then repainted.

adding color and celebrating local identity. This led to a local news story last year when one of the 70-pound fiberglass statues, owned by Canton himself and painted with a hybrid Cuban/American flag motif, was stolen as part of a college prank before being remorsefully returned, and then repainted.

But I’ve saved the best for last. Karja Hansen and I have never met in person, but we have several friends in common and follow each other on Facebook. She is generations younger than I am but, like me, has an intense interest in city design. I first noticed her when she was a junior associate at the well-known new urbanist architecture firm Duany Plater-Zyberk; while at DPZ, she wrote a moving essay about her participation in planning for the revitalization of several blocks of long-outdated public housing in Montgomery, Alabama that lie on the route of the historic Selma-to-Montgomery civil rights march.

Today, Karja has moved on from DPZ and taken up the cause of preserving and improving Little Havana, where she founded and leads a new entrepreneurial space called the Barrio Workshop. Here’s a description, from an article written by Moebius (I‘m sensing that everyone knows everyone in LH):

“Karja has been working on plans for a 14,000 square foot space that will serve in large part as a co-working space, hosting everything from a conference room [that] a home-based business owner might want to use on occasion to dedicated desks and lockers for entrepreneurs to incubator spaces for small offices or an entire small business. On the site she also plans a:

- certified kitchen (where food products could be prepared);

- cold storage space for local produce;

- woodworking studio;

- sewing and silkscreening studio;

- pottery studio;

- small cafe.

“Part of the space will be flexible so it can host events.”

Sounds fun, no? Karja also wants to create a “penny university” in Little Havana. The article continues:

“Poliphili Penny University will emphasize knowledge-sharing in the neighborhood, offering peer-to-peer classes and workshops on practical skills like how to restore a bungalow or how to create wood mouldings and do plasterwork, as well as topics like getting historic designation for a property. Participants will also gain hands-on knowledge in Barrio Workshop's spaces such as the pottery and woodworking studios.

“‘In August I'm planning to launch the first of a three-part series called Anatomy of a Bungalow,’ says Karja. ‘The first part will cover the history of the bungalow, construction and renovation.’”

On the Barrio Workshop’s Facebook page, Karja writes about “Producing Intellects, Citizens, Craftspeople, Community, and well made goods.” Idealistic? Oh, yeah. Keep at it, I say.

I can’t say that everything is right in Little Havana. The National Trust’s concerns have not been dispelled, and I know from Karja and others that there is serious concern about demolition of some of the neighborhood’s bungalows, particularly in East Little Havana. Some beauties have already been lost to make way for mediocre new development.

But my impression is that the district is teeming with both old and new energy, has both fighters and creative spirits, and continues a proud tradition of ethnic music, art, food and community. If you care about a place, wouldn’t you want people like Moebius, Fuller, Canton, and Hansen on your side? I’m sure each of them could name other impressive neighborhood animators with their own stories and, heck, judging from her website, Moebius could probably name a hundred. As with every other city neighborhood, Little Havana will continue to evolve, but I love its chances to evolve well.

Related posts:

- Preserving a sense of place in LA's Little Tokyo (April 9, 2012)

- The green dividend from reusing older buildings (January 24, 2012)

- 'Weed bombing' turns blight to bright in Miami (December 8, 2011)

- The greenest (historic) building is the one that's in the right context (June 16, 2011)

- Revitalization with palm trees: the green revival of Northwood (September 29, 2010)

- Miami 21 leads the way on zoning reform (January 7, 2010)

Move your cursor over the images for credit information.