Why I support the DC building height restrictions

Posted November 19, 2012 at 1:24PM

I’ve been procrastinating this one for a long time. I generally avoid taking stands on controversial local issues in Washington, where I have lived for over four decades, and I am especially uncomfortable being at odds with people I respect and consider friends.

That said, I can’t sit on this any longer: the law that restricts the height of buildings in DC is under attack from all sorts of sources (many of them out-of-towners or relative newcomers to the city, probably not a coincidence). Some of the critics are indeed friends, but I disagree with them on this particular issue.

I’m here to say that, although there are pros and cons to the height restrictions, the city and its residents are better off with them than without them. In my opinion, the restrictions should stay, pretty much as they are. (Be warned that, having procrastinated writing this for so long, I now have a lot to say. I hope this will be persuasive, but it will not be brief.)

Before I get into the specifics, I want to state some caveats. First, I am not expressing an official position of the organization I work for, NRDC. As an organization we seldom get involved in local DC issues at all, and we haven’t discussed this one. I’m speaking for myself only. Second, while I come out decidedly on one side of the issue, I think it is one on which reasonable people can differ according to their values and which values they weigh more heavily than others.

Putting the issue in context

The law governing building heights in Washington is somewhat more complex than many people realize. It restricts buildings to 20 feet taller than the adjacent street, up to a maximum of 90 feet on residential streets, 130 feet on commercial streets, and 160 feet on Pennsylvania Avenue downtown. (In many neighborhoods, zoning is more restrictive.) The effect is that, in downtown and other highly-valued commercial areas, new buildings in the city generally rise to 10 or 11 stories; developers max out their allowance, with the result that most new buildings in the hottest commercial parts of the city have the same height.

By comparison, New York City’s One World Trade Center, now under construction, will rise to a symbolic height of 1776 feet, when its pinnacle tower is included. 104 stories will be habitable. Vancouver, increasingly a city of skyscrapers, reportedly has 50 buildings of at least 100 meters (328 feet) in height; building heights are restricted in some places, however, to protect designated view corridors, particularly of mountains and the ocean.

Paris is more like Washington. One of the world’s most beautiful and beloved cities, the French capital has generally restricted building heights in the city center in relation to the streets the structures border, with a maximum height of 121 feet for new structures. As a result, when one stands on top of the hill in Montmartre, the vista reveals a mid-rise central city, with buildings of six or seven stories. The views of such prominent landmarks as the Notre-Dame cathedral, the golden dome of Les Invalides, the church of St-Eustache, the Louvre and, of course, the Eiffel Tower, are generally unblocked; conversely, when one stands in the Musée d’Orsay on the Left Bank of the Seine, one has a clear view up to Montmartre, with the flamboyant basilica of Sacré-Coeur on top.

There is also the 1970s skyscraper Tour Montparnasse, of course, sticking out like a sore thumb; that’s what prompted Parisians to demand a more specific restriction on building heights. And the modern inner suburb of La Défense is filled with skyscrapers, but for the most part Paris is a city of lovely, moderately scaled buildings and beautiful vistas. In central Barcelona, another much-loved city, buildings other than the major cathedrals tend to be between five and ten stories. The same is true in Prague.

All of these cities famous for their mid-rise beauty are now facing their own skyscraper debates, however. In Paris, for example, the city council has recently raised the height limit to 590 feet in certain districts, including the 13th, 15th, and 17th arrondissements to the south and west of the city center. Taller buildings have also been approved in parts of Prague. Is the concept of a mid-rise central city endangered? Should it be?

Opposition to the building height restrictions

A lot of people seem to think so. Strong critics of the DC building height restrictions include, among others, my friend Chris Leinberger, libertarian economist (and suburban Boston dweller) Ed Glaeser, The Economist’s Ryan Avent, my fellow Atlantic Cities writer Emily Badger, prolific blogger Matt Yglesias, and one of my favorite urban thinkers, DC architect and Washington Post columnist Roger Lewis. The popular local urban affairs blog Greater Greater Washington has run several features about the restrictions, including editor David Alpert’s “Should the Height Limit Change?” earlier this month. The (mostly) fair, presenting-all-sides (against the restrictions, for them, various in-between schemes) article had drawn 119 comments as of this writing, very few of them in support of current law.

The arguments against the height limit boil down to these, more or less:

- Under current law, DC cannot grow because it is running out of room.

- By restricting the supply of housing, the height limit is making DC unaffordable.

- Urban density creates better places and a better environment and should not be restricted.

- The height limit leads to mediocre architecture and city design.

Or, as a highly animated commenter put it in a recent meeting, “Washington is a low-density, provincial, backwater town because Congress will not allow it to grow.” (Never mind that he recently moved here from mid-rise Barcelona, which he loved. And, in case he’s reading, I should add that he’s a nice guy with whom I expect to have commonality on other issues.)

My reasons in favor of a mid-rise city

Here’s why I disagree:

- Actually, DC can grow under current law. In 1950, with the height restrictions fully in effect, the city’s population was 802,178. In 2011, its estimated population was 617,996. The truth is that we were a “shrinking city” until about a decade ago, and we are nowhere near full capacity today. Maybe the reason developers say we “can’t grow” is because we may be running out of large, undeveloped sites suitable for mega-projects. Personally, I don’t see why that’s a bad thing: I think it would be better for the city (if not for large developers) to add new buildings in a more incremental, fine-grained way on smaller parcels as their current uses go out of service. (A more analytical presentation of the facts supporting DC’s room to grow under current law may be found in testimony earlier this year to a Congressional subcommittee, presented by the Committee of 100 on the Federal City.)

- A lot of other things are going well under current law, too. As Derek Thompson wrote in The Atlantic, Washington is the richest and best-educated metro area in America, leading the nation in economic confidence. Far from being “provincial,” Washington has become one of the most cosmopolitan cities in the country, attracting visitors from all over the world. It is also a long way from being “low-density”: It may not be as dense as New York, San Francisco or Boston, but Washington is significantly denser than many large US cities with skyscrapers, including Baltimore, Oakland, Seattle, Portland, Denver and San Diego. If you’re looking for an example of a low-density city, try Kansas City (1,630.4 persons per square mile of land area, as compared to Washington’s 10,065), Phoenix (2,797 persons per square mile), Dallas (3,518 persons per square mile), or Atlanta (4,020 persons per square mile), all of which have skyscrapers.

- Building height has little to do with affordability. The argument that a limit on building height restricts housing supply and thus leads to higher prices is essentially the same argument made against Portland’s urban growth boundary. In both cases, it’s hogwash: if affordability were closely related to building height and density, New York City and San Francisco would be the two most affordable big cities in America.

- Just because urban density is good doesn’t mean that more is always better. I couldn’t agree more with the proposition that sprawl has been horrible for America and that generally increasing the density of our built environment – especially above what we built in the second half of the 20th century – is essential to a more sustainable future. I’ve staked my career on it. But the key is to increase average density all across a metro area so that the region’s footprint doesn’t expand; parts of the region that are already relatively dense, such as downtown Washington, are fine as they are.

This is supported by research: the environmental benefits of increasing density – including lower rates of driving and stormwater runoff (when measured in the watershed as a whole) – are dramatic indeed as density increases from large-lot sprawl to village-style densities of 20 units per acre or so. But, above a certain point, the environmental benefits of incremental increases in density taper off. There is little additional benefit to these environmental indicators, for example, as density increases beyond about 60 homes per acre, as one might find in a three- or four-story apartment building. Indeed, there is even some evidence that taller buildings create negative environmental impact per increment of additional space compared to building heights typically found in central Washington or Paris. Taller buildings need stronger support materials that require greater amounts of energy to produce.

- In any event, denser doesn’t necessarily mean taller. These numbers may surprise you: Barcelona is denser than New York City, housing 41,000 people per square mile compared to New York’s 27,000. Barcelona’s beautiful and thriving, mid-rise central district L’Eixample is denser than Manhattan, at 92,000 people per square mile compared to Manhattan’s 71,000. It does not have buildings taller than Washington’s. In DC, we could increase density substantially by incrementally converting many aging one- and two-story buildings in commercial and mixed-use districts to a still-human three to five stories.

- Architectural mediocrity has nothing to do with building height restrictions. I’ll grant that Washington, like just about every other American city, has some lousy commercial architecture. (It also has some very good newer commercial architecture, in my opinion.) And, when buildings are mediocre, their shortcomings may be magnified by a uniform height. But, my goodness, how can one say that lifting the building height restrictions would help? Maybe it’s a matter of taste, but to my eyes the unrestricted high-rise architecture of the denser suburban centers near our area’s Metro stations – probably a decent approximation of what we might get downtown without the height limit – is worse, ranging from boring to awful. My favorite of the area’s newer, transit-accessible suburban projects is the more moderately scaled Bethesda Row, a lively, mixed-use development built well within the parameters of the DC limitations.

- Taller buildings can have a negative effect on the quality of light and tree cover. Paris is called la ville lumiére (city of light) for a reason. Its wide boulevards and mid-rise buildings allow much more light into the city center than do the frequently shaded skyscraper streets of, say, Manhattan. The same is true in Washington. The benefits are partially medical: sun and bright daylight stimulate the brain’s production of serotonin, which enhances mood and staves off depression. Research shows that the brighter the daylight, the brighter the spirit; conversely, limited exposure to sun and bright daylight is associated with symptoms of depression.

On a related topic, the amount and quality of light have an effect on the natural environment, too. My NRDC colleague Geoff, who advocates increased density in his own neighborhood, says he nonetheless supports DC’s height limits “because of the trees.” He may be on to something: New York City’s tree cover is at 20.9 percent, below the national average of 29.9 percent (based on a 20-city study by researchers from the US Forest Service) and far below the 40 percent recommended by the conservation organization American Forests. Washington’s tree cover is 35 percent. While surely there are many contributing factors, the two cities have very similar climates and one would not expect such a large disparity. Light is likely one of the reasons.

- The importance of Washington’s vistas and distinctiveness should not be underestimated. This observation may be somewhat subjective, but I believe one can see farther and better in DC than in other large American cities, and this distinguishes Washington from other places. It’s partially the views of the iconic national monuments, of course: one can see the Washington Monument from all over the city, and the view from the Virginia side of the Potomac River into the city is truly breathtaking. One of the places sometimes cited as a candidate for taller buildings is the Southwest Washington waterfront; if they were allowed there, some of those views as we now know them (from, say, the Mount Vernon bike trail) could be significantly compromised.

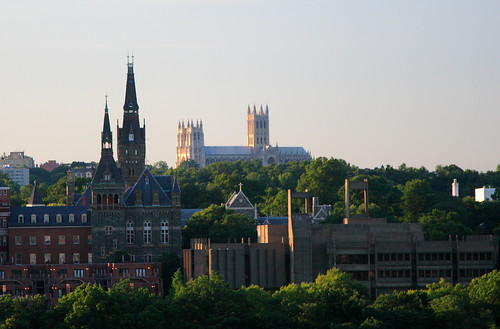

But this is critical: it isn’t just the views of the monuments: in Washington there are many places where one can see other notable landmarks such as Washington National Cathedral, the Shrine of the Immaculate Conception, the spires of Georgetown University’s Healy Building, or the Potomac River itself, just to name a few. It's also the feel of the neighborhoods: even without long-range vistas, neighborhoods like the wonderful Dupont Circle would feel totally different surrounded by taller buildings. This is a big part of what makes DC special, and I wouldn’t mess with it.

Put another way, it’s bad enough that our suburbs look like everywhere, USA. Let’s not let that happen to our central city.

What others have said

Larry Beasley, former planning director for skyscraper-rich Vancouver, argues that DC’s lack of taller buildings is a significant civic asset. Greater Greater Washington’s David Alpert reported on a talk by Beasley:

“[Beasley believes that the] height limit brings many benefits of its own. For one thing, it makes DC particularly notable and memorable, which Beasley pointed out is increasingly valuable in a world economy where most mid-sized cities are increasingly undifferentiated and unremarkable.

“It draws tourism, gives greater prominence to key national symbols, and creates a ‘coherent frame of walls around ceremonial spaces.’ It also reduces the economic incentive to tear down historic buildings.”

Alpert’s article counters that few tourists would be bothered by tall buildings outside of the city’s core but, to me, this is not just or even primarily about the tourists.

As I have written repeatedly, I think smart growth and urban advocates have made too much of a fetish of density while neglecting many of the other things – including moderation – that can soften the potential harshness of city life and create more human, more environmentally sound neighborhoods. We were and are right to reject suburban sprawl, but in our advocacy we have overreacted, forgetting that density is not the goal but only one of many useful tools for achieving the real goals of livability and sustainability.

The prolific champion of cities Richard Florida, who coined the phrase “creative class” to describe an emerging US economy of innovation and collaboration, agrees that density can lose its appeal beyond a certain point:

“Stop and think for a moment: What kind of environments spur new innovation, start-ups and high-tech industries? Can you name one instance, one, of this sort of creative destruction occurring in high-rise office or residential towers, in skyscraper districts? The answer is no . . . Similarly, you don’t find great arts districts and music scenes in high-rise districts but in older, historic residential, industrial or warehousing districts such as New York’s Greenwich Village or Soho, or San Francisco’s Mission District, which were built before elevators enabled multi-story construction.”

Rob Steuteville persuasively argues in Better Cities & Towns that the real problem isn’t insufficiently dense central-city downtowns but, rather, sprawling suburbs. Relating this point to the Washington region, in 2004 my NRDC colleague Deron Lovaas contributed an extraordinarily well-researched chapter to the Encyclopedia of Energy. In it he cites a 2001 study finding that, if the region were to adopt the suburb of Reston’s density of nine to ten homes per acre, it would be able to accommodate 25 years’ worth of growth on vacant and underutilized land within 20 miles of Washington’s center.

The architecture of creativity and lovability

Perhaps the most eloquent defense of Washington’s building height limits was written earlier this year by my friend, long-time Washingtonian, and long-time smart growth advocate Ed McMahon, now a senior fellow at the Urban Land Institute, a developer think tank. His article “Density Without High-Rises?” appeared initially on Citiwire and was republished elsewhere. It is rich with good information and well-articulated opinion, including this passage:

“In truth, many of America’s finest and most valuable neighborhoods achieve density without high rises. Georgetown in Washington, Park Slope in Brooklyn, the Fan in Richmond, and the French Quarter in New Orleans are all compact, walkable, charming — and low rise. Yet, they are also dense: the French Quarter has a net density of 38 units per acre, Georgetown 22 units per acre.

“Julie Campoli and Alex MacLean’s book Visualizing Density vividly illustrates that we can achieve tremendous density without high-rises. They point out that before elevators were invented, two- to four- story ‘walk-ups’ were common in cities and towns throughout America. Constructing a block of these types of buildings could achieve a density of anywhere from 20 to 80 units an acre.”

Ed agrees with Richard Florida that the liveliest and best neighborhoods, those that “foster local entrepreneurship and the creative economy,” are seldom if ever high-rise havens. In DC, he points to Capitol Hill, the U Street Corridor, and NOMA as examples. I’m not sure I agree with him about NOMA, which is currently being developed as somewhat bland, monolithic and overscaled (evidence that we should think twice about trusting DC developers), but he’s right about the general point, and he could just as easily have cited, say, the upcoming neighborhoods of H Street, NE or LeDroit Park.

Another point that I have made repeatedly, citing another friend, the built-environment sage Steve Mouzon, is that buildings and places need to be lovable in order to be sustained. That may be a mushy concept to many, and it certainly can be elusive to pin down. But I believe we ignore it at the expense of both sustainability and our quality of life. This is pertinent because, while DC has its share of mediocre buildings (as I noted above), its overall impression is immensely lovable in my opinion. Ed agrees, and argues that our building heights are part of the reason:

“Washington is one of the world’s most singularly beautiful cities for several big reasons: first, the abundance of parks and open spaces; second, the relative lack of outdoor advertising (which has over commercialized so many other cities); and third, a limit on the height of new buildings . . .

“I love the skylines of New York, Chicago and many other high-rise cities. But I also love the skylines of Washington, Charleston, Savannah, Prague, Edinburgh, Rome and other historic mid- and low-rise cities. It would be a tragedy to turn all of these remarkable places into tower cities. Density does not always demand high-rises. Skyscrapers are a dime a dozen in today’s world. Once a low rise city or town succumbs to high-rise mania, many more towers will follow, until the city becomes a carbon-copy of every other city in a ‘geography of nowhere.’”

Larry Beasley, speaking on the occasion of the DC Height Act’s centennial in 2010, agrees and emphasizes that the law is not just about tourism and the national monuments:

“[The Act’s effect is] not just about expressing national power. It’s about the joyful pleasure of walking down a gently scaled street, of unexpectedly coming upon a magnificent public edifice that stands proudly superior to the mundane buildings around it . . . It’s about the frantic life of our modern world being made more bearable . . .

“Be very careful as you gamble with the 100-year legacy of Washington’s Height Act. Take care not to open things up too casually. I dare say, those height limits may be the single most powerful thing that has made this city so amazingly fulfilling.”

Beasley’s passage was cited in the Congressional testimony of the Committee of 100 on the Federal City, which I mentioned earlier.

Is there a middle ground?

Almost no one, of course, is arguing that the building height restrictions should be repealed completely. Here are some of the partial-repeal suggestions that I have seen:

- Keep the restrictions in the city’s “monumental core” – basically the area around the National Mall – only.

- Keep the restrictions only in the area covered by the city’s original plan created by Pierre L’Enfant (bordered roughly by Rock Creek, the Potomac River, and the Anacostia River to the west, south and east, and by what is now Florida Avenue to the north).

- Allow taller buildings only in designated newly redeveloping areas, such as the Southeast waterfront bordering the Anacostia River, the Southwest waterfront bordering the Potomac, and/or Poplar Point, east of the Anacostia in Ward 8, the city’s poorest district. (This prompts the question, will white people who don’t live nearby ever stop offering opinions about Anacostia?)

- Raise the height limit everywhere to 160 feet, as it now exists for Pennsylvania Avenue.

- Allow building rooftops, where small utility penthouses now frequently stand as exceptions to the height limitations, to be developed as habitable indoor space.

- Grant height “bonuses” above the current statutory limits in exchange for public benefits. (In David Alpert’s article, this is articulated as when the increased height "allows a really interesting, attractive design, and if the building provides some amenities, like parks or daycares or libraries or something that won’t otherwise be economically viable.”)

- Auction off a limited number of height waivers each year in designated areas outside of special places such as important viewsheds.

- Allow taller buildings around Metro stations.

There are actually endless variations, many of them thoughtful. As I said at the outset, this is an issue on which reasonable people can and do hold differing opinions.

Let’s just don’t

But my own preference is to leave the height limits as they are and enforce them. Once you’ve made a change, in any place or regard, it is essentially irrevocable. And, once you’ve made a change in any place or regard, you’ve stepped onto a slippery slope that makes other changes more likely.

Let’s just don’t. While almost any of us, given the opportunity to create a new scheme, might come up with something that differs from current law in one respect or another (such as 120 or 140 feet instead of 130, or treating Pennsylvania Avenue the same as the rest of the city), the truth is that Washington has been doing better economically than at any other point in its lifetime, and we’re doing great as a wonderful place to live, too. To the extent we have problems (diminishing affordability, substandard architecture here and there), raising the height limit won’t help at all. It also won’t help environmentally, compared to other ways of raising density in our region.

Why the heck change, especially when, as McMahon and Beasley articulate so well, DC’s mid-rise cityscape is one of its distinguishing, much-loved assets? Tinkering with a successful status quo is a solution in search of a problem.

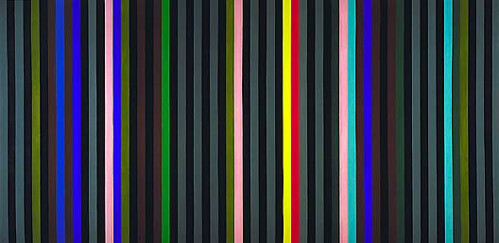

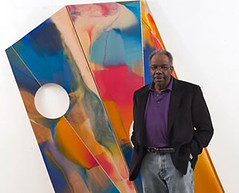

Some years – um, decades – ago, I attended a lecture and tour at the Corcoran Gallery of Art on the Washington Color School of painting. It was led by the late Gene Davis, a DC native and central figure in that bright, vivid style practiced by such additional luminaries of the 1960s-1970s art world as Morris Louis and Kenneth Noland; its influence continues to the present day with, for example, the highly regarded DC artist Sam Gilliam. It is said to be “one of the greatest post-World War II art movements in the US,” characterized by an abstract merger of order and flamboyance.

The one thing I remember most from that very interesting event was Davis’s assertion that the Color School was associated with Washington for a reason: it could not have happened in New York, he said, because the quality of light there wasn’t the same.

That’s all I have.

Related posts:

- Managing the increasing urbanization of Washington: sensitivity required (May 29, 2012)

- Smart growth is a start. But it's not enough. (April 24, 2012)

- Why lovable places matter to sustainability (February 14, 2012)

- A spiffy green waterfront begins to take shape in DC (January 19, 2012)

- The messy issue of design in smart growth (January 6, 2011)

- The environmental paradox of smart growth (April 9, 2010)

- Unofficial Washington: how architecture shapes the real city (November 24, 2008)

Move your cursor over the images for credit information.