Stabilizing & greening the favelas: Rio's formidable challenge

Posted October 21, 2013 at 1:33PM

Rio de Janeiro is one of the best-known cities in the world. Its spectacular topography and beaches, its music, the world’s most famous pre-Lenten carnival. And, yes, they know a thing or two about how to play soccer there. The world’s eyes will be on Brazil’s cultural capital next year, when the country hosts one of the world’s two largest sporting events, the World Cup, and again in 2016 when Rio will host the Olympic Games.

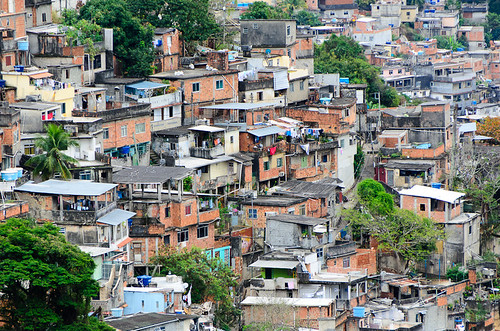

For the city’s boosters, however, there’s a major fly in the ointment, in the form of Rio’s world-famous favelas, or shanty towns on the city’s outskirts. These informal settlements are in effect handmade cities in themselves – housing some 1.4 million of Rio’s total population of 6.3 million – in homes quite literally piled on top of each other, and out of reach of city services, many without sanitation, water, electricity, or even streets. Most are also beyond the reach of the law, ruled by drug cartels called traficantes.

Writing two months ago in the New York Review of Books, Suketa Mehta offers a startling description of the contradictions of life in the favelas:

“One night in Rio, Walter Mesquita, a street photographer, took me to a baile funk, a street party organized by the drug dealers, in the unpacified favela of Arará. It was an extraordinary scene: at midnight, the traficantes had cordoned off many blocks, turning the favela into a giant open-air nightclub. One end of the street was a giant wall of dozens of loudspeakers, booming songs and stories about cop-killing and underage sex. Teenagers walked around carrying AK-47s; prepubescent girls inhaled drugs and danced. On some corners, cocaine was being sold out of large plastic bags. Everybody danced: grandmothers danced, children danced, I danced. It went on until eight in the morning.

“Although such parties are officially prohibited in the pacified favelas [where the state has gained control] because of their multiple breaches of the law, ranging from noise violations to exhortations to murder—even the music played there is called baile funk proibidão—the state and its forces were nowhere to be seen.”

Mehta goes on to describe a daytime ride in a police helicopter in which the pilot refused to fly over Arará for fear of being shot down by the traficantes’ anti-aircraft guns.

Many favelas not controlled by traficantes are instead controlled by militias of corrupt police. Mehta continues:

“The militias don’t allow drug dealing by the traficantes, but they make money in protection, cable TV, transportation, loan sharking . . . The militias create unwritten, though widely obeyed, rules for neighborhoods: you can’t leave your home after a certain time; if you rape women, you’ll be killed publicly in a ceremony. Your radio can’t be too loud. The punishment is often torture or the death penalty. The militias sell arms to traffickers; they deal drugs when necessary; they employ guards who are former traffickers expelled from gangs.”

Mehta paints a chilling scene of lawlessness. Gradually, though, conditions are improving. According to an article written by Andrew Downie and published two years ago in Time, in the past few years the authorities have taken control of several high-profile favelas, sending in special-operations police to remove the traffickers and then installing a community-based presence called Pacifying Police Units, or UPPs by their Portuguese initials:

“The results have been overwhelmingly positive. In the metropolitan area, crimes such as murder and assault are down significantly, as is the number of people killed in confrontations with police. Favelas like Cidade de Deus, or City of God, which is home to the biggest UPP (and the setting of the famous 2002 Brazilian movie by the same name), have seen a massive increase in drug seizures and arrests, while homicides and robberies have been almost halved. ‘I've been here 43 years, and I've never seen it as good as it is now,’ says Cidade de Deus resident Eunice Malta. ‘Before it was not life: I would stand here and a gang would come by shooting at everything that moved. Now my kids come and go as they please.’"

This is important progress, but only a first step.

Can the government also extend infrastructure and basic city services to its poorest residents? Downie continues:

“Rio has plans to integrate all its favelas by 2020, but residents can't wait that long for health, education, water, transport and, most crucially, employment opportunities. The success of the UPPs, if not the city's future, depends on whether pacified favelas can be transformed even further into regular neighborhoods with the same security, commerce, services and leisure as the rest of the city."

City officials hope the answer is a program called Morar Carioca, a comprehensive program to bring the settlements fully into the city by extending public services, improving individual homes, and constructing new housing and infrastructure, such as pedestrian passageways and, where feasible, streets that will allow sanitation trucks to pass through the rehabbed neighborhoods. In a minority of cases, where current homes are on unstable ground, structures will be razed and residents relocated. This has drawn fierce resistance, but it seems hard to argue with, given the precarious topography of Rio’s outlying areas.

Last month, Morar Carioca was recognized by the C40 City Climate Leadership Group as one of ten major city innovations working to fight the sources and impacts of climate change.

In its citation for the “sustainable communities” category, C40 noted that Rio’s program also contains two green pilot projects:

“At Babilônia and Chapéu Mangueira, two favelas located at Leme (next to Copacabana), the focus of the project was to reduce carbon emissions whilst spurring sustainable practices and approaches such as LED outdoor lighting and selective waste collection. At Babilônia, the City of Rio built 16 “green houses” and paved the Ary Barroso Hill, which provides access to the communities, with a mix of asphalt and recycled car tires.

“So far, 68 favelas are being re-urbanized, providing direct benefits to more than 65,000 households, with a total investment of 2.1 billion reals. The aim is to keep people within their own communities, only relocating those currently occupying areas under high risk of landslides. Since 2009, nearly 20,000 families have been relocated, and the goal is to resettle all those living under risky conditions [by] 2016.”

Paula Alvarado, writing in Treehugger, stresses the intersection of sustainability and basic human services in the program:

“Interventions - which are executed by workers from within the community when possible - are varied and holistic, and they include installing sewage collection (grey waters run down on open gutters in most of favelas), running water, rainwater collection (to prevent slides), access and transportation facilities (stairs, elevators, cable cars, whatever fits, both for elder people and for workers to be able to provide services such as trash collection), and the relocation of families whose households are installed in risk areas.

“’Our office is not focused on works, but on people: works are done to deliver citizenship to those families,’ said Jorge Bittar, Secretary of Housing, to Treehugger in an interview in Rio. ‘As incredible as it seems, even the proper use of sewage is something that needs to be the subject of special care and education: people are not used to it and they may throw objects that block the pipes.’”

Visible new projects include a cable car system, new housing, a child development center, a job center, and a cultural center.

Forty architecture firms were selected to work in 40 different areas of the city. The emphasis isn’t on changing the look and feel of the favelas (or on gentrification) so much as it is on enabling them to function better for their current residents. While the program emphasizes upgrades to public space, it also incorporates work on houses’ interiors, both to strengthen their structure and to improve quality-of-life-issues. Alvarado reports that it is not a formula of pre-set improvements but a case-by-case plan for each house made by an architect and a social worker after a series of interviews with the dwellers.

I encourage a reading of Alvarado’s article especially for a summary of the green features of the two pilot projects.

The question, of course, is will the effort be enough? Gaining and maintaining security, installing infrastructure, extending city and social services, upgrading homes, and providing new public assets, all with an overlay of sustainability, for well over a million people in less than a decade is a heavy lift, especially given other, concurrent major projects such as the upgrading and greening of Rio’s port facilities. The task seems so large, and resources inevitably limited, even with the World Cup and the Olympics on the horizon. One can’t help but worry that money will dry up after the Olympics are over in 2016.

I am certainly far too removed from the process to venture an informed guess as to what the future will hold. But I am encouraged that some success is being realized already, and I can only hope that each increment of improvement will breed another, until the momentum becomes strong enough to attract private investment and spur additional, lasting change. The aspiration is certainly commendable, as C40’s honor recognizes.

Watch this one-minute video for a quick visual introduction to some of the work that is being done:

Related posts:

- An amazing, entertaining vision for greening Rio's working port (April 26, 2013)

- The beautiful game brings dignity to the streets (August 6, 2010)

- Cincinnati students plan redevelopment area of Brazilian city for the next World Cup (July 29, 2010)

- Vancouver’s medal-worthy Olympic Village, one of the greenest neighborhoods anywhere (February 12, 2010)

Move your cursor over the images for credit information.

.