How the complete streets movement is improving our communities

Posted November 4, 2013 at 1:22PM

To say that my friend Barbara McCann is a bicycling enthusiast is to engage in more than a little understatement. She and her husband Bob have bicycled in more countries than most of us will ever visit in any fashion, and it’s a 100 percent safe bet that their next vacation will continue their travel tradition of riding far, steep, and enthusiastically. It came as no surprise, then, that the opening passage of Barbara’s new book, Completing Our Streets, begins with a description of a bike ride.

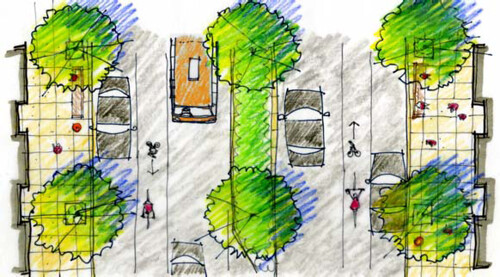

That bike ride in Atlanta in the 1990s - on a street perilous for cyclists - it turns out, was one of the moments in her history that led Barbara to join with others in founding what we now know as the “complete streets” movement, and to dedicate the last dozen or so years of her career to its leadership and success. As the book details, that movement – based on the simple but powerful notion that streets should safely accommodate not just automobiles but also pedestrians, bicyclists and public transit users – has caught on with fervor. If you live in one of the hundreds of communities that have recently adopted policies favoring such measures as new types of crosswalks, slower vehicular traffic in areas where there are pedestrians, and more prominent bicycle lanes, chances are you have noticed that many streets look and feel different - more thoughtfully designed, with more than just cars in mind - than they did, say, twenty years ago.

I am lucky to live in such a community (Washington, DC) where, depending on circumstances, I am at times a driver, a pedestrian, a cyclist, and a transit user. And, where these kinds of changes have been made, I feel safer and better accommodated as a pedestrian and cyclist – and, remarkably, not at all inconvenienced as a driver.  Traffic pretty much moves as well (or as poorly) as it always has, and in some cases, it moves better because everyone’s spaces are better delineated. These changes are largely the result of complete streets thinking and advocacy.

Traffic pretty much moves as well (or as poorly) as it always has, and in some cases, it moves better because everyone’s spaces are better delineated. These changes are largely the result of complete streets thinking and advocacy.

This is not to say that I have no quibbles with complete streets. I wish green street features – such as strategically designed landscaping and paving to capture stormwater – were a more explicit and routine part of complete streets advocacy. The times when we make changes to the road surface to incorporate safety features are great times to incorporate environmental features as well. (To be fair, Barbara says as much in her brief chapter 9, which cites Boston’s “complete-and-green” example and suggests how the complete streets concept might be expanded.)

I also wish some forms of traffic calming designed to slow cars - techniques associated with complete streets - didn’t also inconvenience bicyclists. And I wish that complete streets proponents paid more attention to additional important issues such as street connectivity and the design and function of the buildings alongside our streets, and how both influence walking.

But it must be said that the complete streets movement has been as successful as it has been precisely because of its laser-like focus on the accommodation of different types of street users. The book stresses that the movement aims for pragmatic, incremental improvement, not utopia:

“This book . . . does not paint a vision of an ideal future or provide a template for the ‘perfect complete street.’ This book is not the cutting-edge design manifesto that some people may expect. Plenty of others have created beautiful, innovative templates for multimodal streets and compact, walkable towns and neighborhoods. But I’ve found that those finely crafted visions are not of much immediate use in the communities I see as my baseline: Atlanta and the small towns across Georgia and the suburban United States. These places, and so many more across the United States, have been shaped by sprawling development. It will be quite a while before they reach any sort of smart growth ideal— if ever. But the people who live there still need to be able to reach their neighborhood schools safely and walk to and from the bus stop.”

As Barbara writes, some of the most effective implementation strategies for improving streets on the ground lie not in big capital improvement projects but in the most mundane repair projects and in the details of development codes. The book explains the advantages of bringing about change “not through big signature projects but through small, gradual improvements.” There is even a section of chapter 5 called “The Value of Incremental Change.” I think she is right about that.

Especially given these goals, it is hard to quarrel with the movement’s accomplishment:

“We formed the National Complete Streets Coalition in the early 2000s to push for passage of complete streets policies. The policies— in the form of laws, resolutions, or internal agency directives— commit states, cities, and towns to building all future road projects to safely accommodate everyone using them. The movement took off: since 2005, more than half the states and close to five hundred local jurisdictions have adopted complete streets policies.

“Many of the communities that have made this commitment are going on to study the long-standing gaps in their transportation network, rework their decision-making processes, write new guidance, and educate transportation professionals and citizens alike in the new approach to making transportation investments. From the state of North Carolina to the city of Chicago and from Edmonds, Washington, to Lee County, Florida, they are beginning to routinely build their roads differently: they integrate carefully engineered sidewalks, safer crossings, bicycle lanes, new types of intersections, traffic calming, and features that speed buses to their destinations.” (Emphasis added.)

Indeed, the book is as much a guide to how to build a successful advocacy movement as it is to better street design. As noted in a press release issued simultaneously with Completing Our Streets, the book “discusses how practitioners and activists have changed auto-oriented systems by focusing on three strategies: reframing the way we think about streets, building a broad base of support, and creating a clear path to a multi-modal process.”

It’s hard to overstate how fundamental a change the movement has wrought in the way we think about such an important part of our communities. This is an important success story, containing many individual success stories within. Written by the movement’s founder and leader (who also happens to be a very good writer), Completing Our Streets is now the definitive book on how communities can work together to make streets safe for all users.

For a possible companion volume, check out the Urban Street Design Guide, recently compiled by the National Association of City Transportation Officials. I was sent a review copy and, if Completing Our Streets will be especially useful to advocates, the Guide may be especially useful to municipal officials, designers and engineers. Extending its coverage beyond the roadway, the book's central point seems to be that urban streets are public places and have a larger role to play in communities than solely being conduits for traffic. I agree wholeheartedly. I confess that, so far, I have only thumbed through the book, but I intend to spend more time with it.

Related posts:

- What good, grassroots advocacy for complete streets looks like (May 3, 2013)

- Are Main Streets a thing of the past? Is that OK? (February 4, 2013)

- What makes a great city street? Consider these examples (September 6, 2012)

- Streamlining the process for people-oriented streets (June 26, 2012)

- Cartoon gives new meaning to 'complete streets'! (April 10, 2012)

- What's wrong with this picture? Horribly unsafe street design, for starters (March 23, 2012)

- Fixing suburbs with green streets that accommodate everyone (December 20, 2011)

- Complete streets policies are gaining popularity across the country (April 27, 2011)

- St. Louis leads with model project for smart, green streets (October 19, 2009)

Move your cursor over the images for credit information.

.