Think globally, act regionally: large-scale sustainability planning

Posted March 12, 2008 at 10:18PM

One of the biggest challenges to managing the way we grow and develop land, or the way we conserve land, is that our settlement patterns and our ecosystems do not match up with the way that we are organized to make decisions, the way we are organized politically.

The Washington, DC metropolitan area, for example, comprises not just seven counties and the District of Columbia but also ten independent cities in the states of Maryland and Virginia. That’s not counting the scores of towns and cities that are also parts of counties.

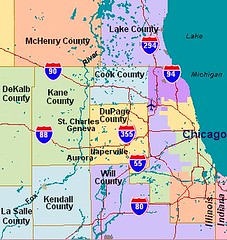

In greater Chicago, a researcher working a decade ago identified a staggering 267 municipalities and counties, along with an incredible total of some 1250 “governments” of one sort or another, including various school and service districts and regional authorities.

In greater Chicago, a researcher working a decade ago identified a staggering 267 municipalities and counties, along with an incredible total of some 1250 “governments” of one sort or another, including various school and service districts and regional authorities.

Much of NRDC’s policy work is oriented toward the federal government, or the governments of the states, plus work with city governments in our big-city offices, especially New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago. All of these authorities have influence over land use, but all are also unsatisfactory venues for finding remedies: the federal government’s influence over private land use can be profound, but it is often indirect; the states have more direct authority, but some regions span multiple states, and many municipalities have stronger authority than their host states; the big-city governments usually have no jurisdiction over the places where sprawl is occurring and natural landscapes are threatened.

My own work tends to be either at the neighborhood scale or the metropolitan scale. Those are very productive and creative places to think about regional growth and smarter development. But another, potentially important, scale is emerging that can help our thinking: the megaregion.

These are places that are tied together geographically and economically, and are composed of multiple metropolitan areas. Last year I was involved in a book that identified nine such regions, and some of the thinkers involved with the project have now added another, for a total of ten: Cascadia (the Pacific Northwest), Northern California, Southern California, the Arizona Sun Corridor, the Texas Triangle, the Gulf Coast, Florida, The Piedmont Atlantic, the Northeast, and the Midwest/Great Lakes.

The framers of the national planning initiative America 2050 put it this way:

By mid-century, more than 70 percent of the nation’s population growth and economic growth is expected to take place in extended networks of metropolitan regions linked by environmental systems, transportation networks, economies, and culture. These emerging “megaregions” are becoming the new competitive units in the global economy, characterized by the increasing movement of goods, people, and capital among their metropolitan regions. Just as metropolitan regions grew from cities to become the geographical units of the 20th century global economy, megaregions – agglomerations of metropolitan regions with integrated labor markets, infrastructure, and land use systems – are rapidly taking their place.

While some very important and rapidly developing places (e.g., Denver, Kansas City, Nashville) are left out of this frame, I think these folks are onto something. Some of the issues that may be especially suited to megaregional planning and even (gasp) governance include intercity rail transportation networks, watersheds, and ecosystem conservation, just to start. Most of the states in the Northeastern megaregion have long worked together on air pollution issues, and have more recently joined together in the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative to develop regional strategies for addressing global warming.

Indeed, the granddaddy of all megaregions is the Richmond-to-Boston northeastern corridor, first identified by geographer Jean Gottman as “Megalopolis” in the late 1950s. The Regional Plan Association, based in New York, has published some telling maps of the megaregion, including the two above.

The map on the left shows the region’s natural areas, with areas currently enjoying protection in dark green; rural or other natural areas are in light green; and the yellow areas are already urbanized. It essentially shows current conditions. The map on the right, however, shows what could happen if current trends are not altered: the existing developed area (as of 2000) is again shown in yellow; the additional area that under current trends will be developed by 2025 is in bronze, and the additional area that under current trends will be developed by 2050 in red-orange. That’s a sobering vision, to say the least.

RPA has published a very thoughtful and enlightening paper on the various characteristics of the Northeastern megaregion, and how we might avoid the worst-case scenario through such measures as a regional smart growth compact and cooperative landscape and estuary conservation. It’s a good blueprint for thinking about growth, development, and sustainability on a large scale.