Sprawl's share of new US housing starts has declined dramatically, says EPA

Posted March 3, 2009 at 1:32PM

A new report from the US Environmental Protection Agency documents a dramatic shift in the pattern of new development in the nation over the past two decades: Central cities and counties are now claiming a much larger share of overall regional development, and sprawl locations are claiming a much smaller share, than in the early 1990s.

This enlarges and confirms the terrific work by Dr. John V. Thomas of the agency's Development, Community & Environment Division ("the smart growth office") that I began to report here last year. It is also consistent with demographic trends and the geography of changes in home values in the current real estate slump.

This enlarges and confirms the terrific work by Dr. John V. Thomas of the agency's Development, Community & Environment Division ("the smart growth office") that I began to report here last year. It is also consistent with demographic trends and the geography of changes in home values in the current real estate slump.

In particular, Thomas examined US Census data on residential building permits for the 50 largest metropolitan regions in the country over an 18 year period from 1990 to 2007. He compared the number of permits issued by central cities and core suburban communities in those regions to the number issued by suburban and exurban communities.

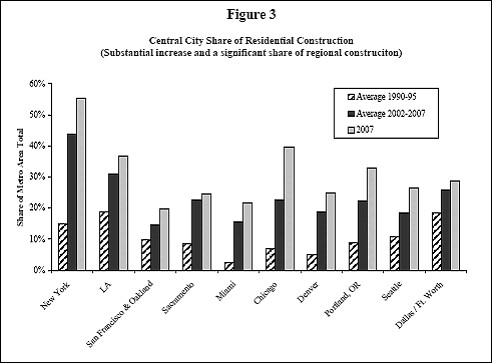

Although the shift in the geography of development has not been uniform, it has been common throughout the country. In roughly half of the metropolitan areas examined, urban core communities dramatically increased their share of new residential building permits. See, for example, the bar graph from the report depicting the changes in ten regions, below:

In 15 of the 50 regions studied, the central city more than doubled its share of permits. New York is one of them. In the early 1990s, New York City issued only 15 percent of the residential building permits in its region. Over the past six years, by contrast, it has averaged 44 percent. Chicago saw its share of regional permits rise from 7 to 23 percent over the same period.

The report found that the increase in central city share has been particularly dramatic over the past five years. In 2007, building permits everywhere declined the real estate market downturn, but the shift inward continued. Thomas believes that this acceleration of residential construction in urban neighborhoods reflects a fundamental shift in the real estate market.

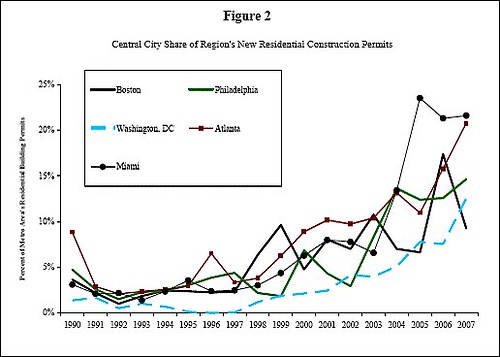

Here is what the trend looks like in five regions on a line graph:

When inner suburban counties are included in the analysis, the shift is even more dramatic. For example, the report finds that the city of Chicago's share of new residential construction permits in its greater metro region climbed to 40% in 2007 (from just 7% in the early 1990s); but Cook County's share climbed to 50% (from 25%). Add in what Thomas calls the "1st tier suburban counties" and the combined share of permits issued in inner locations in 2007 reached 73%. The share claimed by fringe counties decreased from 38% to 26% in the same period.

In some places, smart growth policies may be playing a role, says the report:

"The clear trend toward more redevelopment has a couple key implications for smart growth. First, regions often cited as leaders in promoting growth management and redevelopment (Portland, Denver, Sacramento and Atlanta) are among the medium sized cities where the shift inward has been most dramatic. Second, in metropolitan regions with large and diverse central cities with strong ties to the global economy (New York, Chicago, Boston, Miami, Los Angeles),

the market fundamentals are shifting toward redevelopment even in the absence of formal policies and programs at the regional level."

I believe the report directly challenges the assumption that sprawl is inevitable or that "most development will occur on the fringe," no matter what policies and incentives we pursue.

The report is careful to concede that, in many locations, the trends are difficult to discern for varying reasons, and that the central city share of growth remains small in many locations. (Interestingly, many of these are in the Rust Belt.) But Thomas also believes that, because of limitations in the way jurisdictional data are reported in the census, the amount of infill and redevelopment (as opposed to greenfield development) in suburban jurisdictions is not captured by the analysis; nor is some suburban transit-oriented development. A superficial reading of the data may actually understate the degree to which the market has shifted in the direction of smart locations.

Download the report here.

The development market that we are witnessing today may not be the same one we witnessed ten or even five years ago. This is the new trend we must nurture.