Miami 21 leads the way on zoning reform

Posted January 7, 2010 at 1:21PM

I’ve been meaning for some time to write about the progressive new zoning framework, Miami 21, adopted by the city of Miami last fall. But it’s a bit of a complicated and somewhat abstract subject.

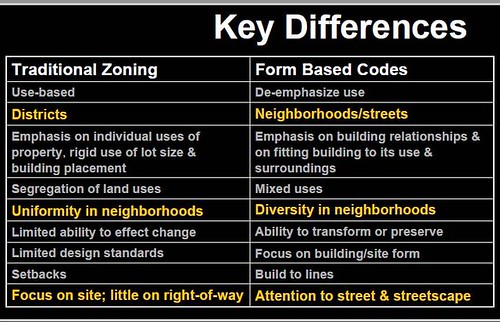

The nutshell is that Miami 21 is a form-based code that regulates building types and sizes (“forms”), and their relationship to the street, rather than traditional “Euclidean” zoning that segregates land uses from each other.  Under a Euclidean code, for instance, it will often be illegal to open a coffee shop or dry cleaner’s in or next to most residential neighborhoods. Euclidean zoning districts also tend to be large, so that large tracts of land become isolated monocultures of commercial, industrial, single-family residential, or whatever; this virtually guarantees an automobile-oriented culture since distances between common trip origins and destinations are, in effect, mandated to be beyond walking range. Form-based codes are much more compatible with the goals of smart growth.

Under a Euclidean code, for instance, it will often be illegal to open a coffee shop or dry cleaner’s in or next to most residential neighborhoods. Euclidean zoning districts also tend to be large, so that large tracts of land become isolated monocultures of commercial, industrial, single-family residential, or whatever; this virtually guarantees an automobile-oriented culture since distances between common trip origins and destinations are, in effect, mandated to be beyond walking range. Form-based codes are much more compatible with the goals of smart growth.

Anthony Flint, director of public affairs at the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, wrote in The Boston Globe in 2006:

"You know, a lot of this problem could be solved if we just changed zoning.

“That's right. Those rules for what gets built and where - spelled out on color-coded maps hanging in most every town hall. Soaring gas prices have made a lot of us yearn to drive less, walk more, and work near home. OK, you say. Let's start arranging ourselves differently - let's build neighborhoods where we don't have to jump in the car for every errand. But zoning rules in Massachusetts and across the country forbid proximity. Most municipalities strictly prohibit what planners call ‘mixed-use’ development: homes jumbled together with shops and restaurants and offices. In other words, the traditional New England town center, or Roslindale Square, or Back Bay.

“What we need is to abolish zoning as we know it. Start over. Short of that, we should change the most outdated provisions that stand in the way of compact, concentrated development.”

That’s what Miami 21 does. A form-based code works to make everything compatible through developmental design and orientation, promoting walkability and a sense of place. It is more about how the interaction among buildings and streets create a neighborhood. This is how the Form-Based Code Institute (now there’s an attention-grabbing name for an organization) puts it:

“Form-based codes address the relationship between building facades and the public realm, the form and mass of buildings in relation to one another, and the scale and types of streets and blocks . . . This is in contrast to conventional zoning's focus on the micromanagement and segregation of land uses, and the control of development intensity through abstract and uncoordinated parameters to the neglect of an integrated built form.”

While some good neighborhood development has taken place in Miami and elsewhere under current law, the problem is that in almost every case it has required regulatory exceptions to do so.  Rather than being the norm, smart growth has borne the extra burden of justifying zoning variances case by case. The biggest accomplishment of the new framework will be a lightening of that burden.

Rather than being the norm, smart growth has borne the extra burden of justifying zoning variances case by case. The biggest accomplishment of the new framework will be a lightening of that burden.

Sadly, the local AIA chapter, progressive as ever, opposed Miami 21, finding it overly prescriptive. Some of their criticisms, such as an insufficient emphasis on expanding transit, may not be misplaced. But it isn’t like the code can’t be supplemented by other additional policy measures and tweaked where experience indicates a need for improvement. And it certainly isn’t like AIA offered a better idea for a policy to promote sustainability and walkable neighborhoods.

Daniel Nairn, one of my writing cohorts in the Sustainable Cities Collective, has done a superb job of introducing the politics surrounding Miami 21. Apparently it is still not an entirely done deal, since the enabling law hasn’t taken effect yet. But implementation seems likely, and there will be lots of opportunities for public input along the way as the city fills out the particulars. I think the effect will be positive and quite likely precedent-setting.