Indianapolis can still be a winner in smart growth (part 3 of the Indy revitalization series)

Posted February 8, 2010 at 1:37PM

Football digression to, um, kick off today's post: Congratulations to the very impressive New Orleans Saints for a big win over the Colts in last night's Super Bowl. I was rooting for Indy, but it's hard not to feel good for the Saints' fans, especially the residents of the Crescent City, who have long deserved something new to celebrate. As for the Colts, at least we can make a connection to urbanism: I love the stadium on the edge of downtown Indianapolis where the team plays home games, in part because it looks like an actual, if enormous, building (the Saints, who have to play in this monstrosity, may be winners on the field but are not so fortunate in architecture). Now to your regularly scheduled blog post.

About three miles or so from the Colts’ stadium is Indy’s designated smart growth revitalization district, a distressed area with many vacant properties, including a largely abandoned industrial corridor along a rail line, but also good bones for renewal including a resilient population, a good street grid, some stable residential blocks, and prospects for a new, state-of-the-art transit line in the old rail corridor. After a bit of a break from two earlier posts in which I gave an overview (part 1) and discussed what an advisory team including yours truly saw and heard while there last fall (part 2), this installment concludes the series with some thoughts on what strategies might give redevelopment there the best chance of success as a smart, green model project.

Achieving a path of sustainability in the district will be a challenge, and not just because of issues within the neighborhood. For example, Indianapolis as a whole is extraordinarily automobile-dependent: of the nation’s 60 largest cities, it ranks 6th in the portion of its commuters who drive alone to work.  In addition, disinvestment is a well-established pattern in Indiana: the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy found that an astonishing 94 percent of development in the state has been taking place on greenfields, outside of existing areas. (By comparison, in Oregon the portion is 52 percent; in Colorado, 62 percent.)

In addition, disinvestment is a well-established pattern in Indiana: the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy found that an astonishing 94 percent of development in the state has been taking place on greenfields, outside of existing areas. (By comparison, in Oregon the portion is 52 percent; in Colorado, 62 percent.)

The larger context aside, the smart growth district’s potential for sustainable restoration is great. An interesting frame for discussing its potential is LEED for Neighborhood Development, with its consensus-based criteria for sustainable neighborhoods. Let’s look at each of the system’s three major categories:

Location and linkage

In the first, LEED-ND looks generally to where a neighborhood is located within its metropolitan region. This is because a good central or close-in location tends to re-use infrastructure and be more convenient to other neighborhoods, jobs, and assets within the region; research shows that people in such well-placed locations spend far less time in their cars than do those who live on the fringe, substantially reducing emissions of greenhouse gas emissions and other pollutants as a result.

In this case, the district’s location may be its greatest community and environmental asset. It is well within the city’s and the region’s central area, only two miles from downtown.  Not only does this add convenience; it also allows the municipality and new development to save money on infrastructure, which already exists (even though it may require upgrading). The abundance of previously developed building sites also provides the opportunity to improve environmental conditions on what are now brownfields, as well as for the region to accommodate residents and economic growth without further suburban sprawl, with all its attendant problems. (Prior to the current recession, Indiana was losing an average of nearly 40,000 acres of rural land each year to sprawl.)

Not only does this add convenience; it also allows the municipality and new development to save money on infrastructure, which already exists (even though it may require upgrading). The abundance of previously developed building sites also provides the opportunity to improve environmental conditions on what are now brownfields, as well as for the region to accommodate residents and economic growth without further suburban sprawl, with all its attendant problems. (Prior to the current recession, Indiana was losing an average of nearly 40,000 acres of rural land each year to sprawl.)

The district is also served by a number of bus lines, but while there we heard complaints that service was not sufficiently frequent. Restoring the community’s former density should help tremendously in making transit more viable. Of course, a particularly helpful boost to the district’s linkage with downtown and other neighborhoods will come if the proposed light rail line through the community is built, as it should be. I believe the line will be essential to the district’s realizing its full potential for recovery.

Neighborhood pattern and design

The second of LEED-ND’s categories is another in which the district has a very good foundation to build upon, but it is also where it needs the most improvement. To begin, a major asset to the community is its traditional street grid: the district is very well connected, supplying a multiplicity of walking, bicycling and driving routes. This will not only greatly enhance walkability, but also shorten emergency response times for neighborhood residents.

Our team did not have calibrated density data for the district, but it is apparent from the data we had that it is currently nowhere near even LEED-ND’s minimum (7 homes per residential acre, commercial floor area ratio at least 0.5), especially if abandoned buildings are discounted. The community probably was compliant with the minimum before its decline, and restoring and augmenting the district’s density will be essential to bringing a range of benefits, including more shopping and job alternatives, better transportation, greater walkability, and more “eyes on the street” to help reduce crime.

Our team did not have calibrated density data for the district, but it is apparent from the data we had that it is currently nowhere near even LEED-ND’s minimum (7 homes per residential acre, commercial floor area ratio at least 0.5), especially if abandoned buildings are discounted. The community probably was compliant with the minimum before its decline, and restoring and augmenting the district’s density will be essential to bringing a range of benefits, including more shopping and job alternatives, better transportation, greater walkability, and more “eyes on the street” to help reduce crime.

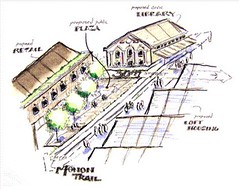

At the same time, it will be important to current residents that the things they like about their community not be lost. As a matter of architecture and design, this can be accomplished by preserving current blocks of single-family detached homes essentially as they are, but with restored completeness by rehabilitating abandoned houses and building appropriately sized new ones on vacant lots. Accessory units such as in-law suites should also be permitted. At the same time, the district can add needed density by building homes and commercial properties in the old rail corridor, where abandoned buildings now stand. Ideally, these would have a variety of scales, from single-family to duplexes and townhouses to multifamily apartments and condos, along with moderately scaled commercial and civic properties. In many cases existing historic buildings can be adapted for these new uses.

It will make the most planning sense to place multifamily buildings and commercial properties in clusters where the light rail stop(s) might be. Neighbors should be thoroughly involved in planning the best location for transit stops, where new development should be placed, and what form it should take. In our planning sessions, it was generally thought that even the largest new buildings would be unlikely to exceed five or six stories, and many could be smaller, retaining the historic scale and feel of the community while still bringing its density up to more viable levels. The idea is to complete the neighborhood, not change it to something unrecognizable.

LEED-ND also encourages mixed-income communities. This will mean adding units for marketing to somewhat more affluent residents, who may be drawn to amenities such as the light rail stop and the nascent design center recently built at one of the main intersections. But, at the same time, it must be stressed that no current residents need be displaced to accommodate the new, given the substantial availability of vacant and abandoned land for building.

If these things are accomplished, the community will attain the critical mass necessary to again support neighborhood-serving retail. Residents should not have to leave their own community to shop for food, health supplies or hardware, visit the bank, or grab a bite to eat. This is partly a matter of convenience, and partly a matter of giving a community a center, a stronger identity and sense of place.

If these things are accomplished, the community will attain the critical mass necessary to again support neighborhood-serving retail. Residents should not have to leave their own community to shop for food, health supplies or hardware, visit the bank, or grab a bite to eat. This is partly a matter of convenience, and partly a matter of giving a community a center, a stronger identity and sense of place.

A rough measure of the district’s current completeness, convenience and walkability can be provided by Walk Score, which most readers know measures a location’s walkability based on how many typical shops, services and amenities are found within walking distance. Normally, inner city neighborhoods score better on this scale than their suburban counterparts. But this is not the case with the redevelopment district, which has a Walk Score of only 38 out of 100 when measured from the relatively central intersection of 22nd Street and the Monon corridor. Despite the district’s central location and favorable street grid the score is lower than the Indianapolis metro average (46) and far lower than the city’s most amenity-rich neighborhoods (the top ten percent score 77 on average). Over two-thirds of the city’s residents have better access to neighborhood amenities than does the redevelopment district.

A reasonable goal might be to raise the community’s score to the city’s average or above within five years, and to the “very walkable” category (70+) within five years of a rail stop’s opening.

Green infrastructure and buildings

Beyond capitalizing on its location and improving the neighborhood’s components and texture, the city will need to do more to achieve its stated goal “of creating a green development demonstration area recognizable as such within 3 years.”

Perhaps the district’s greatest opportunity for additional sustainability achievement lies in the use of advanced techniques for managing stormwater runoff with green infrastructure.  As most readers know, these include such measures as rain gardens, green roofs, vegetated swales, buffers and strips, tree planting and preservation, and use of permeable pavers for sidewalks, street and parking infrastructure. These allow stormwater to be absorbed rather than running off and picking up pollutants on its way to receiving waterways.

As most readers know, these include such measures as rain gardens, green roofs, vegetated swales, buffers and strips, tree planting and preservation, and use of permeable pavers for sidewalks, street and parking infrastructure. These allow stormwater to be absorbed rather than running off and picking up pollutants on its way to receiving waterways.

In the redevelopment district, the potential for these techniques is immense, because so many of the community’s roads and sidewalks need repair or replacement anyway, and there is likely to be so much new building on previously developed sites now covered with impervious surface. Sidewalks represent particularly good opportunities for incorporation of pavers and native vegetation at appropriate intervals, for example, and as streets are upgraded, they can be designed as green, “complete” streets with native landscaping to separate lanes and slow traffic to appropriate speeds.

In our workshops, we were impressed by the green infrastructure concepts proposed by the design teams from Ball State University (see students' conceptual drawings from the workshop), and we recommended that the area’s neighborhood associations and community development corporations, along with the city’s Office of Sustainability,  take advantage of the university’s expertise in crafting a plan and implementation schedule to address these issues. Our meeting with Indianapolis Mayor Greg Ballard suggested that his office also would be fully supportive.

take advantage of the university’s expertise in crafting a plan and implementation schedule to address these issues. Our meeting with Indianapolis Mayor Greg Ballard suggested that his office also would be fully supportive.

Beyond stormwater, the district should also take every opportunity to preserve and re-use existing structures, especially buildings of historic significance, to help preserve community character while conserving energy embedded in the buildings’ construction. Where new buildings are constructed in the district, they should conform to generally recognized green building standards such as those in LEED for new commercial and multifamily construction, LEED-Residential, or the Green Communities standards developed by Enterprise Community Partners. Basic green building techniques are now mainstream and add little if any additional cost.

How to begin

Our team had an extensive set of recommendations, but here are just a few that I think could help substantially. Some could be undertaken right away:

- Undertake infrastructure repair now, especially of broken or deteriorated sidewalks, street pavement, lighting, and street trees. This will provide quick, visible evidence that the city is serious about neighborhood restoration, while also making the community more attractive to private investment.

- Initiate a green infrastructure pilot project in a portion of the district, perhaps an area four to six blocks in size. This, too, would have the benefit of visibility, adding credibility to the city’s efforts without requiring major capital expenditure.

- Institute a program of small grants to homeowners and residents to support property repair and improvement.

- Select, plan and construct a model green, complete street that reduces water runoff, enhances neighborhood beauty, and accommodates all users – pedestrians, bicyclists, and drivers – equitably and safely along one of the district’s main corridors.

The street can become a showcase leading to similar efforts throughout the neighborhood and in other parts of the city.

The street can become a showcase leading to similar efforts throughout the neighborhood and in other parts of the city. - Work with community residents to designate an area of the neighborhood to serve as a walkable center, with moderate-density multifamily residences and an appropriate mix of neighborhood-serving shops and services. Ideally this would be located at a light rail stop. Design and construct the center to qualify for LEED-ND gold or above certification.

- Initiate land banking to control, consolidate and hold vacant properties until they are ripe for redevelopment.

- Build the light rail line, with one or more stops within the redevelopment district. This would be a major boost to the neighborhood’s prospects while helping reduce the city’s unusually high degree of automobile dependence.

- Attain compliance with LEED-ND required minimums (the prerequisites for walkability, density, connectivity, energy and water efficiency, and construction activity pollution prevention) throughout the neighborhood.

Of course, for my architecture and planning teammates and me to make recommendations is pretty easy; for the city and neighborhood to implement them will be much more difficult, especially starting now with the recession. At best, it will take a long period of sustained investment. But I was impressed by the amount of energy and commitment we witnessed while there and, given the successes I have seen elsewhere in similar situations, I’m very hopeful. Indy, make it a winner.

Note: a version of this post also appears on Rooflines, the blog of the National Housing Institute.