The environmental paradox of smart growth

Posted April 9, 2010 at 1:36PM

There is no question that sustainable land use requires, among other things, neighborhood density. Indeed, I have basically staked my career on the proposition that we must increase the average density of our new (and, in some cases, existing) built environment in the US if we are to achieve anything near sustainability as we absorb more growth. Nothing has been worse for our environment than sprawl. Smart growth based on walkable neighborhoods, transportation choices, nearby amenities and the accommodation of an increasingly diverse society – more urbanism, if you will – is the only way we can limit per-capita impacts, and thus total impacts, to a manageable level.

But we also must be honest with ourselves about something, if we are to get this right: Environmental impacts will occur with development; to limit them, we must concentrate them, and this can mean increasing them in some places. This is what I call the environmental paradox of smart growth. Only if we understand the paradox can we address it. Only if we address it can we really create better places in which to live, work, and play – and surely that, not just lowering pollution numbers, must be our real goal.

This is the first of two posts I am writing on the subject, in conjunction with a presentation I am giving at the annual meeting of the American Planning Association. Part two will appear on Monday.

The density imperative

This blog and the sources I cite within it are replete with data showing that increased neighborhood density - as measured by residences per acre, or square feet of nonresidential space per acre - reduces environmental impacts from driving rates and associated emissions, from stormwater runoff, from intrusions on farmland, wildlife habitat, and scenic and cultural resources. There is perhaps no better or more thorough illustration of this than the massive Housing + Transportation Affordability Index recently expanded and published by the Center for Neighborhood Technology (CNT). It shows in 337 metro regions across the country how driving rates, related carbon emissions, and transportation costs are uniformly lower in denser neighborhoods.

Other studies show that denser neighborhoods help protect watersheds. EPA research, for example, proves that developing a thousand homes on a 10,000-acre watershed at an average density of eight homes per acre will reduce runoff by more than two-thirds compared to a density of one home per acre, because the more compact development requires less runoff-inducing street and surface parking infrastructure per household.  Building more densely also saves resource lands: the deservedly acclaimed Sacramento Blueprint, by directing growth in that region to a more orderly and compact pattern over a 45-year period, would conserve 357 square miles of land, including 64 square miles of farmland – while keeping 64 percent of the region’s households in single-family, detached homes. Still other studies show that density improves public health by facilitating walking.

Building more densely also saves resource lands: the deservedly acclaimed Sacramento Blueprint, by directing growth in that region to a more orderly and compact pattern over a 45-year period, would conserve 357 square miles of land, including 64 square miles of farmland – while keeping 64 percent of the region’s households in single-family, detached homes. Still other studies show that density improves public health by facilitating walking.

There is simply no valid solution to global warming, to food security, to ecological conservation – to say nothing about redressing urban disinvestment – without using smart, compact growth to replace sprawl. I happen to think it also creates better environments for people to live in, but I suppose that is to an extent a matter of taste.

But density can increase local impacts

Unfortunately, all these benefits do not necessarily mean that that the NIMBY (not in my back yard) crowd is being irrational when they oppose dense development. Quite the contrary: they intuitively understand that density – especially in the forms in which they have seen it in recent years – can, if not very carefully designed and managed, bring harm to the neighborhood environment.

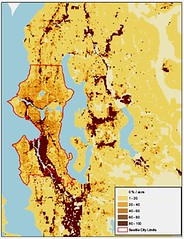

Consider the GIS maps above of metro Boston and metro Seattle. The Boston map on the left shows that, under a smart-growth planning scenario that would direct more growth and building to already-developed areas (and that I likely would support), it is precisely those areas that are increasing in density that will experience increased (if not necessarily by very much) traffic congestion; what it doesn’t show is that some of those areas already have significant traffic congestion. The Seattle map on the right shows that the areas that are the most dense have the most per-acre impervious surface, and thus will generate the most on-site stormwater runoff during rainfall events, which are not infrequent in Seattle. (A per-capita map of impervious surface would show that dense areas have the lowest rates by that measure, but that doesn’t necessarily help the urban watershed.)

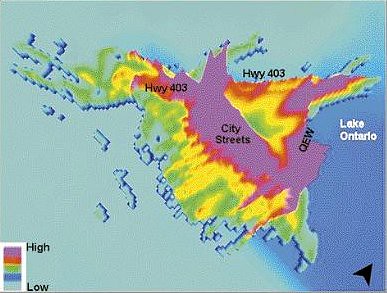

The maps just above show the pattern of transportation-related emissions: carbon dioxide in metro Washington, DC on the left, and volatile organic compounds in metro Hamilton, Ontario on the right. Both show the greatest local concentrations in areas of density. (One might argue that the spatial pattern of CO2 doesn't matter, because the main threat of CO2 is to the planet, not individuals. But the emissions pattern shown for CO2 is not a bad proxy for other driving-related emissions that are more troublesome to individuals, such as nitrogen oxides.)

Impacts on parks and green space

But perhaps no impact of poorly planned neighborhood density is more visible than the loss of green space. Look below at the satellite image of the area around the Ballston Metro station in Arlington, Virginia. By all accounts, Ballston is part of a tremendous smart-growth success story when it comes to transportation performance. The corridor in which it sits has absorbed a huge amount of growth with only minimal increases in auto traffic, because so much of the new development is convenient to the Metro. That growth has also been a big asset to Arlington’s tax base. From 1980 to 2005, the 260-acre Ballston station planning area added 6584 new homes, 6.37 billion square feet of office space, and 958,000 square feet of retail. As of 2000, it was home to nearly 11,000 residents (not counting jobs), and I would wager that the population is up to at least 15,000 now.

But almost no new park space came with the influx of new development. Working with my friend Peter Harnik, who heads the Center for City Park Excellence at the Trust for Public Land, we found about two and a half acres, some of which is privately owned and under some access restrictions, of pre-existing and new parkland within the planning area, with another half-acre or so on the way. You can see the markings of their locations on the image.

These pocket parks within the station area add up to about 0.27 acres per thousand people, based on the 2000 population (which is almost certainly lower than the current population).  Peter’s brand-new book, Urban Green, reports that most American cities provide between 5 and 35 acres per thousand, or upwards from 20 times what Ballston provides. (There are some athletic fields outside the planning area boundary to the northeast, but to experience a genuine park of size for urban respite, a Ballston resident would have to walk over a mile, traversing a freeway overpass.)

Peter’s brand-new book, Urban Green, reports that most American cities provide between 5 and 35 acres per thousand, or upwards from 20 times what Ballston provides. (There are some athletic fields outside the planning area boundary to the northeast, but to experience a genuine park of size for urban respite, a Ballston resident would have to walk over a mile, traversing a freeway overpass.)

Ballston is basically a high-rise canyon. I can advocate it to planners, because of its outstanding transportation performance. But I’m in the business of selling smart growth to the public at large, and I have a very hard time selling the likes of this type of development to the public, other than the most committed urbanites.

We can do better than this, and must

I believe we will never succeed in accomplishing the many environmental and community goals of smart growth without earning the broad support of the public, both on a national level and within individual communities. And I submit that we can do much, much better. I’ve argued before (see also here) that smart growth and environmental advocates have been insufficiently ambitious in advocating the better, more compact communities that we all know we must have.

I should add that I have come to this view only over time. For years, I felt that density, location, and transit access were the keys to smart growth, and the more of them, the better, without thinking too much about nuances of community and design. I was wrong about that and, sadly, I fear much of the smart growth movement remains stuck where I used to be. If the legacy of our advocacy is to be a better environment in which to live, we muct become more sophisticated and demanding in what we advocate, whether the debate of the day is about transportation policy, sprawl, reinvestment, or something else.

I should add that I have come to this view only over time. For years, I felt that density, location, and transit access were the keys to smart growth, and the more of them, the better, without thinking too much about nuances of community and design. I was wrong about that and, sadly, I fear much of the smart growth movement remains stuck where I used to be. If the legacy of our advocacy is to be a better environment in which to live, we muct become more sophisticated and demanding in what we advocate, whether the debate of the day is about transportation policy, sprawl, reinvestment, or something else.

Here are at least four ways we can make the neighborhood density that is so essential to smart growth more appealing and green:

- Build appropriate scale and recognize the benefits of incremental density. We don’t need to convert Middle America to the density of Hong Kong, China, or even Ballston in most cases, to improve environmental performance. Sometimes downtown-type density will be appropriate, but the many graphs I have seen plotting the relationship between neighborhood density and per capita driving rates (and emissions) all show that the greatest increments in performance improvement come at the lower end of the scale.

One of CNT’s graphs, for example, indicates that driving is cut by more than half as one moves from large-lot sprawl (one-acre and half-acre lots) to smaller-lot single family homes (around 10 units per acre). Beyond that, we can get further improvement, but only at a much more incremental rate. The graph begins to level out around 20 homes per acre. We accept incremental change much more easily than drastic change.

One of CNT’s graphs, for example, indicates that driving is cut by more than half as one moves from large-lot sprawl (one-acre and half-acre lots) to smaller-lot single family homes (around 10 units per acre). Beyond that, we can get further improvement, but only at a much more incremental rate. The graph begins to level out around 20 homes per acre. We accept incremental change much more easily than drastic change. - Incorporate green infrastructure for stormwater mitigation and livability benefits. Rachel Sohmer of our smart growth staff and many colleagues on NRDC’s water quality staff, along with yours truly, have written extensively about green approaches to stormwater management. Seattle, in particular, has a terrific set of guidelines for incorporating vegetation, green roofs, drainage, pervious surfaces and other low-impact development techniques that allow the urban watershed to thrive (and, in many cases, recover) with density.

Most of these also have the benefit of bringing more nature into the urban landscape, with a range of additional benefits. But green benefits seldom happen by accident. We have to design and build them into our development and infrastructure.

Most of these also have the benefit of bringing more nature into the urban landscape, with a range of additional benefits. But green benefits seldom happen by accident. We have to design and build them into our development and infrastructure.

The density advocates par excellence at CNT have a calculator on the organization’s web site showing how much stormwater one can capture (and thus how much runoff one can prevent) under various scenarios. For example, their pre-loaded scenario “would decrease the site's impermeable area by 42.9% and capture 300% of the runoff volume required. Compared to conventional approaches, the green practices in this scenario will decrease the total life-cycle construction and maintenance costs by 8% (in net present value).”

- Make sure that development offers a rich array of transportation choices. Transportation efficiency is critical to the goals of smart growth, but it is also a key to minimizing the congestion impacts of density.

Some important elements include making sure that the site has a variety of destinations within walking distance, such as shops, services, and amenities; an inviting pedestrian environment that includes sidewalks, street trees, and attractive street frontages (LEED-ND’s walkable streets standards provide great guidance); well-connected streets without dead ends; and, of course, frequent and convenient public transportation.

Some important elements include making sure that the site has a variety of destinations within walking distance, such as shops, services, and amenities; an inviting pedestrian environment that includes sidewalks, street trees, and attractive street frontages (LEED-ND’s walkable streets standards provide great guidance); well-connected streets without dead ends; and, of course, frequent and convenient public transportation. - Build parks and civic amenities into the density. Ballston is hardly the only neighborhood experiencing substantial development without adequate provision for parks and green space. While this may be somewhat easier to do when there is a master developer controlling a larger development, good planning can build amenities into the requirements for parcel-by-parcel development, too.

My friend David Dixon, a relentless density advocate, often speaks of the “density dividend” that can bring civic amenities into a community. These can and in many cases should include libraries, schools, and community centers, too.

My friend David Dixon, a relentless density advocate, often speaks of the “density dividend” that can bring civic amenities into a community. These can and in many cases should include libraries, schools, and community centers, too.

I believe the environmental paradox of smart growth (that compact development can increase as well as reduce impacts) requires that we be thoughtful about our approaches to increased urbanism and make sure that it brings genuine benefits to communities. The fears that surround new development, especially dense development, are understandable and, in some cases, well founded. Heaven knows we have given folks enough crappy projects over the last fifty years to stoke those fears for a long, long time. I would rather address those fears than wish them away.

Simply put, we need more, better, greener ambassadors if we want to make smart growth and urbanism the norm rather than the exception.

Next, on Monday: a gallery of beautiful and innovative density.