The definitive study of how land use affects travel behavior

Posted June 4, 2010 at 1:26PM

Enraged at the spill in the Gulf and the American appetite for oil that ultimately caused it? Stop land development on farmland, forests and other fringe locations and direct future development to close-in opportunities. A massive new study, years in the making, makes it crystal-clear that it can make a big difference.

In particular, transportation uber-researchers Reid Ewing (University of Utah) and Robert Cervero (UC-Berkeley) have published a painstaking ‘meta-analysis’ of nearly 50 published studies on the subject of land use and travel behavior. Writing in the Journal of the American Planning Association, the two return to a subject to which they have dedicated most of their careers, in this case updating their previous meta-analysis from 2001.

What they found: location matters most when it comes to land use, driving and the environment.

The study's key conclusion is that destination accessibility is by far the most important land use factor in determining a household or person’s amount of driving. To explain,  'destination accessibility' is a technical term that describes a given location’s distance from common trip destinations (and origins). It almost always favors central locations within a region; the closer a house, neighborhood or office is to downtown, the better its accessibility and the lower its rate of driving. The authors found that such locations can be almost as significant in reducing driving rates as other significant factors (e.g., neighborhood density, mixed land use, street design) combined.

'destination accessibility' is a technical term that describes a given location’s distance from common trip destinations (and origins). It almost always favors central locations within a region; the closer a house, neighborhood or office is to downtown, the better its accessibility and the lower its rate of driving. The authors found that such locations can be almost as significant in reducing driving rates as other significant factors (e.g., neighborhood density, mixed land use, street design) combined.

The clear implication is that, to enable lifestyles with reduced driving, oil consumption and associated emissions, environmentalists should continue to stress opportunities for revitalization and redevelopment in centrally located neighborhoods. As Ewing and Cervero put it: 'Almost any development in a central location is likely to generate less automobile travel than the best-designed, compact, mixed-use development in a remote location.'

The authors carefully examined each study, applying statistical analysis to tease out which land use factors had the biggest impacts on travel behavior when extraneous factors such as income were controlled. After discussing destination accessibility, the authors continue:

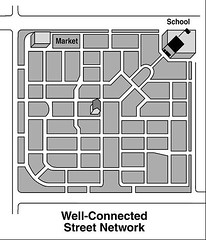

‘Equally strongly related to [vehicle miles traveled] is the inverse of the distance to downtown. This variable is a proxy for many [other factors], as living in the city core typically means higher densities in mixed-use settings with good regional accessibility. Next most strongly associated with VMT are the design metrics intersection density and street connectivity. This is surprising, given the emphasis in the qualitative literature on density and diversity, and the relatively limited attention paid to design. The weighted average elasticities of these two street network variables are identical. Both short blocks and many interconnections apparently shorten travel distances to about the same extent.’

My designer friends have educated me considerably over the past few years on the potential effects of a good street network, and they are thrilled that the study has confirmed their expectations. A whole bunch of Facebook and Twitter updates popped up on the subject earlier this week (mostly referring to this good summary of the study’s discussion of intersection density). None of the updates mentioned the even more critical location findings, but maybe that’s because designers can’t design a location and thus have less professional interest in that aspect. Those who work at the neighborhood scale can affect local street networks, and we are fortunate that some of them are very good at it.

My designer friends have educated me considerably over the past few years on the potential effects of a good street network, and they are thrilled that the study has confirmed their expectations. A whole bunch of Facebook and Twitter updates popped up on the subject earlier this week (mostly referring to this good summary of the study’s discussion of intersection density). None of the updates mentioned the even more critical location findings, but maybe that’s because designers can’t design a location and thus have less professional interest in that aspect. Those who work at the neighborhood scale can affect local street networks, and we are fortunate that some of them are very good at it.

Speaking of street networks, Ewing and Cervero found that they have a huge influence on how much walking is generated from a given location:

‘Among design variables, intersection density more strongly sways the decision to walk than does street connectivity. And, among diversity variables, jobs-housing balance is a stronger predictor of walk mode choice than land use mix measures. Linking where people live and work allows more to commute by foot, and this appears to shape mode choice more than sprinkling multiple land uses around a neighborhood.’

Distance to a store was the second most influential factor in influencing walking, with location and the accessibility of transit next. To an extent, this departs from the findings of the huge SMARTRAQ study of neighborhoods in Atlanta, which found land use mix to be more significant. SMARTRAQ was included among the studies in the meta-analysis, though; perhaps it did not do enough to analyze other variables, or maybe it was just an outlier for some reason.

Interestingly, neighborhood density, when separated from the other factors, was found to be significantly less significant than other factors in influencing both miles traveled and vehicle trips, although still influential. On its face, this would seem to contradict the substantial body of literature that associates increasing density with reduced driving, including the source of one of the graphs in my post earlier this week on stormwater runoff. Ewing and Cervero suggest that perhaps measures of density are inadvertently acting as proxies for other significant factors (‘i.e., dense settings commonly have mixed uses, short blocks, and central locations, all of which shorten trips and encourage walking’).

Interestingly, neighborhood density, when separated from the other factors, was found to be significantly less significant than other factors in influencing both miles traveled and vehicle trips, although still influential. On its face, this would seem to contradict the substantial body of literature that associates increasing density with reduced driving, including the source of one of the graphs in my post earlier this week on stormwater runoff. Ewing and Cervero suggest that perhaps measures of density are inadvertently acting as proxies for other significant factors (‘i.e., dense settings commonly have mixed uses, short blocks, and central locations, all of which shorten trips and encourage walking’).

Transit accessibility is correlated with both reduced miles traveled and more walking, though not to the extent that location and street networks are. Transit use was most closely associated with, in addition to distance from a transit stop, the street network – especially the presence of four-way intersections (for a good explanation of why this may be so, go here).

Ewing and Cervero spend a good deal of space attempting to address the issue of ‘self-selection’ or whether, to give an example, people walk more in places with a good walking environment because they are predisposed to walk and choose to live there, rather than because the environment entices them to. Reid Ewing explained this to me at some length over the phone a few years back, and I understand it, but I’m not entirely sure it matters.  All indications in the market suggest that we have a large, growing, unmet demand for close-in, walkable neighborhoods and an emerging surplus of automobile-dependent environments; research consistently shows that, where walkable neighborhoods in smart locations exist, walking goes up and driving goes down. Unless that unmet demand for close-in, walkable environments somehow turns into a surplus, which isn't happening anytime soon, building more of them will reduce driving and increase walking. The environment doesn't care what the psychological motive is. In any event, the authors found in this case that applying research controls for self-selection might, if anything, show an even more significant influence of land use on behavior.

All indications in the market suggest that we have a large, growing, unmet demand for close-in, walkable neighborhoods and an emerging surplus of automobile-dependent environments; research consistently shows that, where walkable neighborhoods in smart locations exist, walking goes up and driving goes down. Unless that unmet demand for close-in, walkable environments somehow turns into a surplus, which isn't happening anytime soon, building more of them will reduce driving and increase walking. The environment doesn't care what the psychological motive is. In any event, the authors found in this case that applying research controls for self-selection might, if anything, show an even more significant influence of land use on behavior.

Since we tried hard to reward good, accessible locations (while keeping the most remote ones out) as well as intersection density in LEED-ND, I think this research validates our approach. It does make me wonder, though, if we are giving enough emphasis to revitalization and street networks when we advocate in the arena of transportation policy. It also makes me wonder why more environmental groups, clearly incensed at BP and the Gulf oil spill, aren't paying more attention to land use.

Move your cursor over the images for credit information.