'Agricultural urbanism' that actually is urban

Posted July 6, 2010 at 1:35PM

Whether it's called 'agricultural urbanism,' 'urban farming,' or by the seriously awkward word 'rurbalization,' it's all the rage. And, on his excellent blog Discovering Urbanism, Daniel Nairn proposes a model for a ‘garden city block’ that integrates agriculture into city fabric in a really nice way. I’m especially happy to see this, because some (definitely not all) of the contexts in which this sort of thing is presented can be troublesome if you believe, as I do, that keeping our developed regions compact, and our rural landscape rural, are important to sustainability and conservation of our heritage.

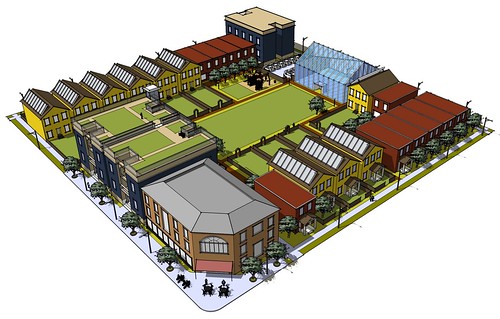

As I wrote in a post last year about urban ‘victory gardens,’ I endorse food production inside cities when it supports density and urbanity, and that is exactly what Daniel’s model does. Based on the urban fabric of Richmond, Virginia’s historic Fan District (photos below), Daniel’s model retains the streetscape of dense, diverse housing and commercial structures, while reforming the interior of the block and adding a green roof and a greenhouse, all for vegetable gardening, and a corner store where some of the harvest might be marketed.

Daniel explains:

‘The exterior of the block functions as in any other urban area. The public streets are activated by the fronts of the buildings and streetscape features, and the full range of transportation access to the rest of the city is available. The interior, on the other hand, is devoted to the more constrained social scale of the block community, and the structures serve as a wall protecting this garden area. Enclosure is necessary to provide a degree of privacy, to protect produce from theft and vandalism, and to keep animals from wandering.

‘By the numbers, this block allows a density of 15 [dwelling units per acre while keeping 28% of all land for growing produce.’

Those are good city numbers. Viewing the block from the street, you have no doubt that you are still in a city:

Daniel continues:

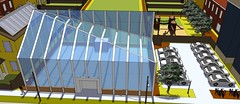

‘Gardening requires many resources that can be shared by the whole block. A tool shed is accessed from the side by the glass elevator. A water cistern collects and stores runoff from the buildings above. Chicken coops are lined up against the building. Although chickens need sunlight, some shade could benefit them as well. Maybe they could be on wheels. The composting bins are directly in front of the block's dumpster, so households can deposit their organic waste while taking out the trash.’

Good stuff. Visit the post for more illustrations and context.

Now, me, I’m the kind of guy who grew up in a poor family just a generation removed from dirt farming for sufficiency and couldn’t become a big-city boy soon enough. There’s nothing romantic or therapeutic to me about compost and chickens, both of which conjure disturbing images from my childhood. But I know a growing phenomenon, in both senses of the word, when I see one.

Urban agriculture is catching on, and we need to do it in a way that does not undermine the considerable benefits of compact cities and regions. Unfortunately, the contexts in which I usually see this discussed are so-called ‘agricultural urbanism’ that looks way too much like a new attempt to justify expanding suburbs onto rural land; and proposals to demolish buildings in central urban cores to convert property to farming, essentially on the premise that those 'shrinking' cities will never rebuild (even though almost all of them continue to expand their suburbs). Those approaches are not wholly without rationale, but I believe both could end up doing more harm than good (see here and here). Daniel’s suggestion is a refreshing concept that brings some of the benefits of urban farming without as many of the risks.

Move your cursor over the images for credit information.