Are you ready for the country? Rural communities & smart growth (part 1 of 2)

Posted August 3, 2010 at 1:29PM

In this blog, I’ve probably written more about disinvested city neighborhoods, and their recovery and restoration, than about any other subject. But our small towns, and particularly their traditional town centers, have been every bit as disinvested as their urban counterparts - as economies have soured, younger generations seeking a better life have fled, and Main Street businesses have been sapped of life by big-box chains out on the highways. While many city neighborhoods are now finally on the rebound; I’m not so sure about small towns in rural America.

Perhaps the ones hit hardest have been those that were bypassed by the Interstate Highway System. In the past few decades, whatever new businesses were established tended to choose locations by freeways where they could draw automobile traffic, not in older centers that were less visible and accessible to drivers. With intercity travel shifted to the Interstates, people didn’t even pass through the old towns much anymore. (Small towns near growing metro areas suffered a different kind of displacement: a near-total loss of character in many cases as they were gobbled up by sprawl and transformed into bland suburbs.)

Consider, for example, Fulton, Indiana (above), my mother-in-law’s home town. As of the 2000 census, its population was only 326, “99.69%” white, according to its Wikipedia entry. In the satellite photo, though, the street layout looks classic, the kind of thing my new urbanist planner friends might design today. It is compact, connected, and walkable. And it’s smack in the middle of the Corn Belt, as the cropland surrounding the little community on the image attests. Eight and one-half miles up the highway is Rochester, the Fulton County seat, population 6,416; in the other direction is the nearest “big city,” Logansport (population 19,350), 15 miles away. Fort Wayne is 74 miles away.

The appealing satellite photo of Fulton, unfortunately, belies the conditions within. See the two photos of Main Street, above. The town’s Walk Score, measured from the center, is only 29, classified as “car-dependent,” due to a lack of services and amenities within walking distance of the center. Google shows a church, a school, and a tavern placed inside the community, but that's about it for what's in their database.

Fulton County does have a comprehensive plan, published in 2008, for which the residents of the town of Fulton were surveyed. They like a lot about their community, including the “down home atmosphere,” the low crime, the school system, the proximity to larger cities, and the “freedom of expression and living.” But they also identified weaknesses, including abandoned and condemned buildings, too many junk vehicles, “not enough pride in properties,” and not enough for teens to do. That said, the median household income is not bad for a rural town, at around $44,000 per year.

Another town I am familiar with, Chesnee, South Carolina, is shown above. Chesnee, population 1003 in 2000, and more ethnically diverse than Fulton with a 28 percent African American population, is right on the North-South Carolina border. I pass through it often when driving from the Charlotte airport to visit family in Asheville. Nearby is the Cowpens National Battlefield, where the American colonists won a decisive victory over the British in 1781. The nearest city, Spartanburg (population 39,673), is only 19 miles away. Chesnee is surrounded by small farms, some forest land, and scattered home sites.

There’s not a lot to Chesnee, but it is pleasant in its way. One gets the impression that its low-rise town center once had a certain vibrancy, even though today it appears to have lost its zing. And unlike Fulton, the rest of the community is not particularly compact or logically arranged. Chesnee is also a substantially poorer community than Fulton with a median household income of $25,089. But from the point of view of planning, its center - which is at a crossroads (literally) - provides some decent architectural bones if conditions improve to support a recovery. Measured from the center, the town’s Walk Score is 55, “somewhat walkable.” There are still a pharmacy (above right), a clinic, some food markets, bank branches, eateries, and places of worship inside the town limits, a few right in the center.

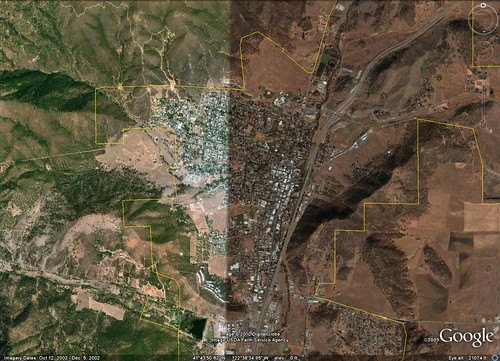

Above is another satellite image, and not a very good one, of the last community that I want to introduce today, Yreka (wye-REE-ka), California, where my cousin Mary Ellen lives. It’s the biggest of the three at population 7,290 (2000), and to my impression the most self-contained. Perhaps significantly, it is on the route of Interstate 5 as it makes its way between.the substantial cities of Redding, California (population about 100,000, 98.5 miles south) and Medford, Oregon (76,850, 51 miles north over the Siskiyou Pass).

Yreka has a colorful history, having been a part of the mid-19th-century California gold rush, and still being the closest town to the majestic Mount Shasta. It is surrounded by the Klamath and Shasta National Forests. Yreka sees a lot of tourists, and part of its downtown is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Demographically, it is 87 percent white, with other ethnicities including Native Americans (6 percent) and Hispanics/Latinos (5 percent). Its population is only slightly more prosperous than that of Chesnee, with a median household income of $27,398.

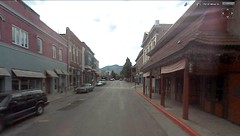

The town’s architectural and planning assets for sustainable placemaking are very good, in my opinion. It has a walkable grid, is not terribly hampered by sprawl (though there is some, especially by the freeway), and has a substantial number of community amenities and services in town for a place of its size. Its Walk Score in the center is a commendable 82, rated “highly walkable.”

Still, Yreka has suffered some downtown disinvestment, with a significant amount of local shopping having shifted to the Walmart Supercenter and adjacent strip center two and a half miles to the south. Yreka also has the eldest population of the three, with 19 percent aged 65 or older.

I think these three communities are as good as any to represent at least the part of rural, small-town America that is likely to remain rural. (I’ll save the discussion of rural communities changing into suburbs for another time). They each are facing an uncertain future. Do the teachings of smart growth, born of concerns about sprawling metro areas, not rural towns, have any applications here? Some people think they do, and that will be the subject of my next post.

Move your cursor over the images for credit information.