Why doesn't the public health community get it about walkability?

Posted September 1, 2010 at 4:52PM

With the exception of some real heroes in the field such as Dick Jackson and Howie Frumkin, I simply Can Not Get public health advocates interested in how the shape of the built environment affects health. I’ve been trying for at least a decade. The field, at least in the environmental community, is built on toxicity of substances and emissions, not environmental factors affecting fitness. So it simply is not a matter of professional expertise or interest to my health-advocate friends. And that’s a real shame, because their presence in the debate could make such a difference.

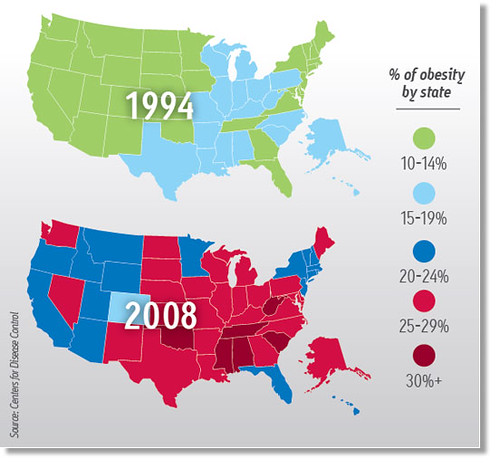

Research proves that sprawl is significantly associated with inactivity and obesity, now perhaps the nation's foremost public health menace. The results of overweight and obesity include increased coronary heart disease, type 2 diabetes, cancers (endometrial, breast, and colon), hypertension, dyslipidemia, stroke, liver and Gallbladder disease, sleep apnea and respiratory problems, osteoarthritis, and gynecological problems (abnormal menses, infertility). Research also shows that walkable neighborhoods and transit improve fitness and the health of communities. Sure sounds important to me.

Finding the synergies between, say, smart growth and health to forge a more holistic approach to our environmental well-being is what sustainable communities should be about, in my humble opinion. I’m not going to stop trying.

I focus on this today because of a provocative article by Steve Miller posted on Eric Britton’s World Streets. I know they won’t mind if I quote the writing extensively, but please visit the site and read it in its entirety. Here’s part:

“To the extent that transportation impacts global warming (it produces about a third of global greenhouse gases), or the livability of our neighborhoods (the transformation of urban villages into isolating suburban sprawl, and perhaps even the pulling apart of today’s multi-generational families, can be partially blamed on the automobile), or the growing diabetes epidemic (significantly caused by obesity which is significantly caused by lack of physical activity)…then how we move around matters.

“In the public health world, the environmental equivalents to road structure are the systemic patterns that make some things easy to do – the ‘default choices’ – and others more difficult. Nearly two-thirds of US adults are overweight, and nearly half of that group is obese. But our ‘obesogenic environment’ surrounds us with opportunities to remain physically passive while we eat too much of faux-foods deliberately manufactured to trigger our evolution-based biological craving for fat, salt, and sugar. ‘Everyone knows that you shouldn’t eat junk food and you should exercise,’ says Kelly D. Brownell, the director of the Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity at Yale. “But the environment makes it so difficult that few people can do these things.

“And, as we all know, like New Year resolutions, dieting doesn’t work. ‘If you take a changed person and put them [back into] the same environment, they are going to go back to the old behaviors,’ says Dr. Dee W. Edington, the director of the Health Management Research Center at the University of Michigan. ‘[But] if you change the culture and the environment first, when you get [personal] change it sticks.’

“As another health researcher has pointed out, ‘Personal life-style is socially conditioned. . . . Individuals are unlikely to eat very differently from the rest of their families and social circle. . . . It makes little sense to expect individuals to behave differently than their peers; it is more appropriate to seek a general change in behavioral norms and in the circumstances which facilitate their adoption.’

“Unfortunately, neither in transportation nor public health have the full implications of this reality been fully absorbed. During the recent debates over national healthcare some of the fiercest attacks were against the ‘nanny state’ proposal to encourage bicycling or the ‘anti-free market’ idea of influencing the food system. On the other hand, the fact that primary prevention and systemic health promotion were even part of the national debate was (minimally) encouraging.

“And a new paper by the new Director of the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), Dr. Thomas R. Frieden, might provide the basis for renewed strategic thinking in both fields, although transportation advocates will have to start by translating some of its ideas and language into their own framework and jargon – a task that the following hopefully begins . . .”

Well worth reading and considering, here.

Move your cursor over the images for credit information.