Sustainable places: where the healing can begin

Posted November 3, 2010 at 1:20PM

Can an urban place be located and designed so that it nourishes and heals? Mark Holland, one of the key principals involved in the planning and certification of the highest-rated development in the LEED-ND pilot program, thinks so.

(The project, by the way, is Vancouver’s Southeast False Creek, which served as the athletes’ village for the most recent Winter Olympic Games, and now has become known as Millennium Water. But that isn't today's subject.)

Holland is one of the founders of the Healing Cities Institute, whose foundation statement explicitly connects human health and well-being with physical place:

“The healing process in the human body is the ability to rebuild, repair and regenerate cells, tissues and organs. Regeneration draws upon the body’s innate intelligence to heal itself.

“What would it then mean for a city to be ‘healed,’ and eventually to reciprocate and be healing and heal itself, its inhabitants and visitors? Furthermore, what methods and processes would support cities to facilitate healing in the context of sustainability planning? How might the built form and natural spaces of the city nurture and develop its residents' holistic health – to include addressing physical, emotional, mental, social and spiritual needs?”

I suspect that, if any of my colleagues are reading this, some are beginning to roll their eyes and thinking about getting back to the next increment of transit funding, subcommittee hearing or whatever. I’ll admit that this sort of language requires at least a generosity of spirit toward those who have an interest in elusive concepts. But, the more I think about the true components of sustainability, the more I believe the subjective is every bit as important as the tangible.

As the Healing Cities group's foundation statement puts it:

“Key findings in the literature review reveal that healing involves much more than curing physical ailments. Healing is a multidimensional process facilitated by integrating physical, mental, spiritual, emotional, and social components of a person’s being. Each component affects the others. This awareness changes the relationship between people and their environments because it recognizes that people do not live as isolated islands, but rather are intimately connected to their surroundings and influenced profoundly by a range of factors.” [Citations omitted.]

Besides, these concepts do get quickly to the tangible. I am particularly impressed by Holland’s Eight Pillars of a Sustainable Community:

- A complete community – land use, density & site layout; mixed uses and incomes, respect for natural areas

- An environmentally friendly and community-oriented transportation system – walkability, transit, complete streets

- Green buildings

Multi-tasked open space – accommodation for both community and environmental needs, community gardens (“Food should be celebrated in the landscape”), active and passive recreation opportunities

Multi-tasked open space – accommodation for both community and environmental needs, community gardens (“Food should be celebrated in the landscape”), active and passive recreation opportunities- Green infrastructure – stormwater management, water/waste/solid waste management, energy and emissions, “eco-industrial networking”

- A healthy food system – food store, restaurants, farmers’ markets, gardens, festivals

- Community facilities and programs

- Economic development (“encouraging the development of real job opportunities appropriate to the income level of the neighbourhood, including live/work opportunities . . .”)

To me, that reads something like the ten principles for smart growth (that some of us crafted with the Smart Growth Network back in the 1990s) might read if we were crafting them now rather than then. Those older principles contain some important elements for smart growth that are not embodied in Holland’s Pillars (particularly with respect to where development should go and the location of communities), but it strikes me that updating and combining the two sets would make a heck of a manifesto. Holland nicely expands on the Eight Pillars of a Sustainable Community in his essay of the same name, which I recommend. Start on page 6.

The wording of the Pillars is slightly altered (for example, “healthy abundance” replaces “economic development”) as they are applied to the frame of the newer Working Group, but the details are the same. Writing in the Vancouver Sun, Kim Davis reports that participants in a recent Healing Cities conference “acknowledged the ‘woo woo’ stigma that arises at the mention of emotional and spiritual needs,” but also that Vancouver planning director Brent Toderian has already moved in that direction by explicitly advocating “beauty” in the city’s planning policy.

Davis spoke with my friend Hank Dittmar, chief executive of The Prince’s Foundation for the Built Environment, who makes the case:

"We thought [talking about zero-carbon housing in a UK project] was a good start, but we thought it maybe ought to be healthy, natural and beautiful as well, so that people would actually want to live in these buildings.

"As Brent has done with beauty, it is time to come out of the closet about our spirits, as well."

Holland’s Eight Pillars evoke not just the Seven Pillars of Wisdom of T.E Lawrence and the biblical book of Proverbs, but also Steve Mouzon’s eight foundations for sustainable places and buildings, four each for places (nourishable, accessible, serviceable, securable) and buildings (lovable, durable, flexible, frugal). Steve’s fearless use of the word “lovable” is what first attracted me to his writing.

As it turns out, Steve has also been writing about healing, in his case with respect to repair of unsustainable suburban development:

“I believe that while the previous era was defined in large part by what we built, this new era desperately needs to be defined by what we heal. Simply put, the suburban sprawl we’ve built since World War II is simply too large to discard. And it’s not ours to discard in any case; it belongs to the people that live there . . . I believe that the healing of sprawl is going to be the great challenge of this new era.”

Some of the places most severely in need of healing are those on the fringe that have been hit hard by the recession:

“The wreckage of the housing bubble is all around us, but not always where we can see it easily, as most of it is located out on the suburban fringe in places nobody visits. Some of it is too far gone, possibly including the houses pictured [above], which have been sitting half-finished for months unprotected in the weather. But there are countless inhabited subdivisions where the houses are finished and inhabited, and where those inhabitants have seen the value of the biggest investments of their lifetimes shredded by the Great Recession. They can’t afford to walk away; what can be done to help them?”

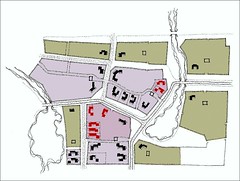

Steve cites his own “Sky Method,” which takes a collective and incremental approach to placemaking, as one useful approach to fixing broken places. While I agree with the incremental approach, the presentation to which he links seems to have been first conceived for greenfield development (it illustrates the conversion of farmland to increasingly intense suburban uses); I like some greenfield projects, but I’m not entirely comfortable with accepting farmland conversion as a given, especially now. In any event, Steve writes in his blog post that because of market forces future greenfield development is going to be the exception, no longer the rule.

Steve cites his own “Sky Method,” which takes a collective and incremental approach to placemaking, as one useful approach to fixing broken places. While I agree with the incremental approach, the presentation to which he links seems to have been first conceived for greenfield development (it illustrates the conversion of farmland to increasingly intense suburban uses); I like some greenfield projects, but I’m not entirely comfortable with accepting farmland conversion as a given, especially now. In any event, Steve writes in his blog post that because of market forces future greenfield development is going to be the exception, no longer the rule.

Steve also writes, correctly, that the same methodology can be applied to already-built subdivisions, a step at a time. And I certainly join him in recommending Galina Tachieva’s new book Sprawl Repair Manual and Ellen Dunham-Jones and June Williamson’s 2009 book Retrofitting Suburbia as great guides for how to go about the process of healing the suburban built environment. Time with their work is well spent, as is time with Steve's.

For the curious, the inspiration for today's title (unrelated to the topic of the post or the blog) may be found here.

Move your cursor over the images for credit information.