Parks for people, and people for parks

Posted April 28, 2011 at 1:33PM

I am leaving today for the annual spring meeting of the Virginia Chapter of the American Society of Landscape Architects, to which I was honored with an invitation to speak. I’m a big fan of ASLA, in no small part because, among nature-loving groups, they get that sustainability requires urbanism just as much as urbanism requires sustainability.

I also think of landscape architects as among “the first responders to climate change,” because they see the effects in their work, day in and day out; they also make cities more beautiful and environmentally functional, which enhances their attractiveness as places to live, work and play. So I’m really looking forward to this opportunity both to share and to learn.

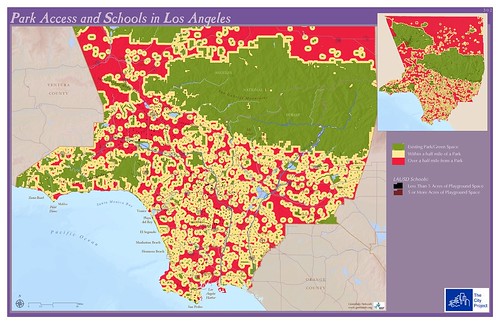

Take city parks, for example. NRDC has long been involved in advocacy for parks, particularly in Los Angeles, where so many of that city’s distressed neighborhoods lack park access. The Trust for Public land has estimated that only a third of the city’s children live within walking distance of a park; all of the areas shown in red on the map above are located more than a half-mile from a park. The obvious answer for park-deprived cities and neighborhoods is to bring more parks into the neighborhoods, as opportunities arise. Bring the parks to the people.

But there’s another, perhaps less obvious, approach that can be deployed in many places: where parks exist, invest in them as catalysts for revitalization and development. Bring more people to the parks.

I highlighted an ASLA video on just that subject last month, and Ben Welle, formerly of TPL, has written about the “symbiotic nature” of parks and population density, recommending strategic upzoning for more development around urban park assets:

“For those living in compact housing around a park’s borders, there is respite, a place to recreate, a back yard where little private outdoor space exists and an amenity that increases property values. For the park, there’s the “eyes” that make it safer, more property taxes to keep it maintained, nearby users to keep it vibrant and able to maximize its value as a public amenity.

“While many parks are historically located in dense urban surroundings, the relationship of compactness and greenspace has not been an area of much attention in urban planning circles.”

Ben cites an initiative in Minneapolis to increase density around a linear park called the Midtown Trail.

The city of Atlanta is similarly hoping that the “emerald necklace” of parks on the Atlanta Beltline loop (example left) around downtown can spur revitalization, and Cincinnati is investing in a major refurbishing of a great city asset, Washington Park, in the hope that it will assist the ongoing recovery of the once-downtrodden Over-the-Rhine neighborhood. In Dallas, when a large corporation rejected the city’s bid for its headquarters because the downtown lacked vitality, the city responded with an initiative to build a downtown park in order to attract more revitalization and residential development, in order to be better positioned for the next opportunity.

The city of Atlanta is similarly hoping that the “emerald necklace” of parks on the Atlanta Beltline loop (example left) around downtown can spur revitalization, and Cincinnati is investing in a major refurbishing of a great city asset, Washington Park, in the hope that it will assist the ongoing recovery of the once-downtrodden Over-the-Rhine neighborhood. In Dallas, when a large corporation rejected the city’s bid for its headquarters because the downtown lacked vitality, the city responded with an initiative to build a downtown park in order to attract more revitalization and residential development, in order to be better positioned for the next opportunity.

Parks need people as much as people need parks.

The Project for Public Spaces cites two successful examples of park-centered revitalization in Houston: downtown, the new Discovery Green Park, which opened in 2008, has attracted “a massive reinvestment in the area, creating an entirely new district where people want to live in downtown Houston.” In an African-American residential neighborhood, stakeholders are re-envisioning Emancipation Park as a “destination that would become the heart and soul of their neighborhood, where local people could find daily inspiration in the culture and history of their community.”

PPS takes a placemaking approach in its work with communities on parks:

“Placemaking differs from traditional park master planning because its principal goal is to create a place that attracts a wide variety of people and an experience that makes them return again and again throughout the year. When design solutions are developed too early and parks are treated as aesthetic objects, the result is often a space that is pleasant to look at but that few people use. People might visit once, but find there are few activities to engage them, which makes them less likely to return.

“In contrast, PPS’s Placemaking approach starts from the premise that successful public spaces are lively places where the many functions of community life take place, and where people feel ownership and connectedness — true common ground. In short, we strive to create places where people want to be.”

Of course, I would be remiss if I did not also cite the immense environmental benefits that people-oriented parks can bring to a city or a neighborhood, from filtering rainwater to releasing oxygen, from helping to cool hot summer temperatures to improving physical fitness and mental health, and more.

No group has a more important role to play in bringing together the economic, environmental and social benefits of parks than landscape architects, and I am looking forward to trading ideas and examples with them today and tomorrow.

Move your cursor over the images for credit information.