The legacy of 9/11 for community & the built environment

Posted September 12, 2011 at 2:33PM

I almost always agree with Roger Lewis, The Washington Post’s longtime columnist and urban savant. His Shaping the City columns, which have run twice monthly since the 1980s, served as an early model for this blog.

But, this time, I’m not so sure. On Saturday, Lewis wrote that the beauty of the nation’s capital has been largely restored since the days of high paranoia and ugly security measures following the 2011 attacks, the bunker mentality that pervaded the city now largely a thing of the past. The print edition of Lewis’s column went so far as to suggest that DC was “safer and more beautiful” than before the attacks, but I note that those suggestions have been dropped from the online edition. Hmmmm.

Lewis is right to a point, of course. The government hastily erected very crude Jersey barriers and other obstacles all over DC’s streets,  sidewalks and plazas in the days following the September 11 tragedy, around anything that could conceivably be a target. These defaced the city’s streetscape and denigrated our public spaces. Some of those have, indeed, been replaced by more attractive obstacles that are better integrated into street and plaza design, as he writes:

sidewalks and plazas in the days following the September 11 tragedy, around anything that could conceivably be a target. These defaced the city’s streetscape and denigrated our public spaces. Some of those have, indeed, been replaced by more attractive obstacles that are better integrated into street and plaza design, as he writes:

“Well anchored, appropriately spaced elements — bollards, trees, planters, benches, trash receptacles, low retaining walls — occupy spaces between street curbs, sidewalks and buildings. A network of curving walkways edged by low retaining walls incised into the landscape makes it tough for vehicles to reach the Washington Monument . . .

“At the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office complex in Alexandria, the General Services Administration and PTO ruled out basement parking garages required by the city, citing the potential risk of a bomb-laden vehicle exploding below one of the buildings. Instead, above-ground parking garages were erected. But a multi-story, 25-foot-deep liner of offices, designed to look like rowhouses, wraps and hides the garages from public view along surrounding streets.”

But.

If he is right about that, there is also a more complete and less favorable story to be told. Let’s start with the PTO example, since Lewis cites it. (My wife works there.) Kudos to them for lining the garages on one side behind attractive office facades. But look at the Jersey barriers scattered all along the sidewalk of the federal courthouse right across the street, slightly shaded in the photo above (PTO’s garage is the right half of the image). That is not what I would call a pleasant and welcoming walkway. Note also the guardhouse in the center of what was probably originally intended to be a public street.

Here’s a view of what used to be a normal public street in my own neighborhood. It is now mostly (and permanently) barricaded with ridiculous little white poles apparently placed to protect offices of the government of Taiwan. That’s not beauty to me.

Not far away, the Department of Homeland Security (which didn’t exist prior to the September 11 attacks) is expanding what is already a major facility within walking distance of my house. Frankly, it’s a little creepy. Sunday as I rode my bike alongside the Dalecarlia Water Treatment Plant, which processes drinking water for the city, I noticed that the fencing with barbed wire on top, which has long been there, had been augmented with Jersey barriers.

There’s more, of a less structural sort: as I wrote in a post about cities and security measures two years ago, military helicopters now fly over my house with regularity, no doubt in part because of the proximity of DHS. That’s a little creepy, too, and a lot noisy. Elsewhere in the city, large government buildings, which used to have multiple public entrances, creating at least a somewhat porous and welcoming pedestrian environment, no longer do; typically all but one or two heavily guarded entrances are now permanently closed, leaving a lifeless streetscape along sidewalks. As I noted in my previous post, if I go to visit EPA's sustainable communities office, as I do with some regularity, I have to walk all the way around their huge building to get to an entrance that visitors can use, identify myself, go through a metal detector, and wait for an escort to come down to the entrance and take me up to the office.

Private corporations have been affected, too (the World Trade Center was privately owned): next to NRDC’s building on 15th Street in downtown DC are the offices of The Washington Post. Shortly after we moved in, I started walking down the alley between their building and ours, mainly out of curiosity, to see what was underneath my office window, on the back of our building. I was stopped immediately by a guard and basically told to stay the hell away, and not very nicely.

Now, it stands to reason that residents of Washington, DC would experience the effects of this Brave New World more acutely than residents of many other US cities. For their sake, I hope so. I would be interested in hearing from readers whether there have been lasting impacts in other cities. Here, it really began before 2011, in the wake of the 1995 bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City; but 2011 sealed the deal, so to speak.

It is clearly not just Washington. (See the Wall Street area of New York, below.) In researching my post two years ago, I found a website called Security Zones and Shrinking Public Space. I just took another look, and here is part of what it says:

“This website summarizes a project outlining the impact of anti-terrorism security on urban public space since September 11, 2001.

“Even before these terror attacks, owners and managers of high-profile

public and private buildings had begun to militarize space by outfitting surrounding streets and sidewalks with rotating surveillance cameras, metal fences and concrete bollards. In emergency situations, such features may be reasonable impositions, but as threat levels fall these larger security zones fail to incorporate a diversity of uses and users.

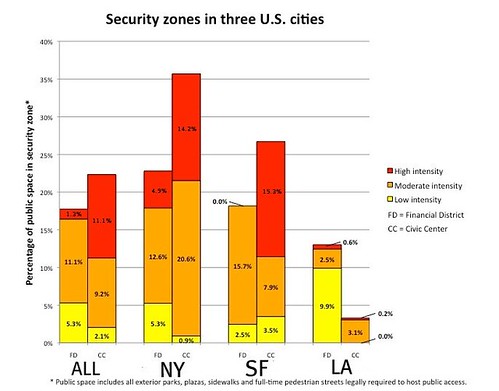

“Utilizing an innovative method developed by our interdisciplinary team, our year-long study of Los Angeles, New York City and San Francisco finds that security zones cover between 3.4% and 35.7% of the public realm in the six districts studied. The ubiquity of these security zones encourages us to consider them a new land use type.”

In a well-researched academic article linked on the site, its author Jeremy Nemeth of the University of Colorado Denver makes a compelling case that the impacts of security in cities are still very much with us, if perhaps a bit more subtly planted now. This reduces access to public spaces, of course, but it also has to affect our well-being. Writing in 2009 on MetropolisMag.com, Julia Galef noted that "the jury is still out on how these security zones affect the way people feel, act, and interact with each other."

I recount all this not to present a counterpoint to Roger Lewis, whom I respect tremendously; I had thought about writing something on this subject last week, well before I saw his column. But maybe he’s a half-full guy and I’m a half-empty guy. I think our public realm, and our comfort within it, have suffered lasting negative effects as a result of the September 11 attacks (and, in my opinion, as a result of our government’s belligerent and exploitative foreign policy reactions that have made us less safe, but that’s another story for another day).

Have we made the security measures a little less ugly in some places over the last decade? Probably. Is my city safer and more beautiful? I say definitely no as to the second count; I can certainly hope so as to the first, but I wish I were more sure that we are safer today than we were, say, on the first or fifth anniversary of the 2011 tragedy.

One last anecdote: earlier in my NRDC career, I did a little lobbying, which took me to occasional meetings in the US Capitol building. One of the great “Washington” pleasures after a meeting there was to walk out the west portico to that magnificent view of the National Mall, with the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial in the distance. I’ve lived here over 40 years and that was never less than a “wow!” moment. Typically, I would walk down those grand Capitol steps where inaugurations are held and then along the Mall back to the office. That experience has been taken away: the west front and access to the grand steps are now closed. Security, you know.

One last anecdote: earlier in my NRDC career, I did a little lobbying, which took me to occasional meetings in the US Capitol building. One of the great “Washington” pleasures after a meeting there was to walk out the west portico to that magnificent view of the National Mall, with the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial in the distance. I’ve lived here over 40 years and that was never less than a “wow!” moment. Typically, I would walk down those grand Capitol steps where inaugurations are held and then along the Mall back to the office. That experience has been taken away: the west front and access to the grand steps are now closed. Security, you know.

Move your cursor over the images for credit information.