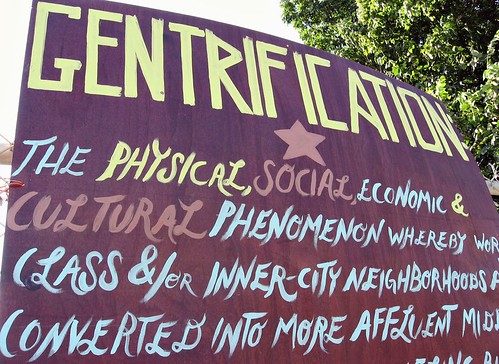

Is 'gentrification' always bad for revitalizing neighborhoods?

Posted October 19, 2011 at 1:23PM

I undertake today’s topic with more than a little trepidation, since it is by its nature emotionally and, not infrequently, racially charged. The title is deliberately chosen but somewhat rhetorical, since the answer ultimately depends on one's definition.

Most urban thinkers agree that the massive abandonment and resulting disinvestment of large areas of our cities by the (largely white) middle class, beginning in the 1960s and only now beginning to be reversed in many places, was terrible for cities, for populations left behind, and for the environment. But many residents whose families remained through those years of disinvestment and until the present day are understandably fearful that addressing these problems by bringing new residents and economic activity into their neighborhoods will only benefit the newcomers while disadvantaging the existing community. The biggest fear is that current residents will be displaced to make room for redevelopment.

There is a political dimension, too, as African-American and other nonwhite populations gained a majority of the voting power in many districts and cities after whites left. If the whites return, minorities’ ability to influence civic affairs and protect interests of importance may be diminished. (Sometimes lost in the equation is that the diminution of the proportion and influence of African-Americans in central cities is due not only to white return but also to middle-class  “black flight” in recent years to suburbs perceived to be safer and with better schools.)

“black flight” in recent years to suburbs perceived to be safer and with better schools.)

Elections now can be won or lost on these issues, as former Washington, DC mayor Adrian Fenty could possibly attest. Fenty’s administration pushed school reform, bike lanes, revitalization and streetcars, all of which were to one degree or another associated by many city residents with a gentrification agenda. Even dog parks became a symbolic issue associated with newcomers in revitalizing neighborhoods. Fenty (whose father is African-American) was tossed out, with voters split along racial lines.

After the primary, Washington Post columnist Courtland Milloy could hardly contain his gleeful contempt for the loser. He leveled many charges at Fenty in his celebratory column, not all of them unfair in my opinion. I’m not so sure about this one, though:

“As for you blacks: Don't you, like, even know what's good for you? So what if Fenty reneged on his promise to strengthen the city from the inside by helping the working poor move into the middle class. Nobody cares that he has opted to import a middle class, mostly young whites who can afford to pay high rent for condos that replaced affordable apartments.

“Don't ask Fenty or [former DC school chancellor Michelle] Rhee whom this world-class school system will serve if low-income black residents are being evicted from his world-class city in droves.”

While many would dispute Milloy’s hyperbole, he was nonetheless expressing the sentiments of a substantial part of the city's electorate. The return of middle-class whites to once-disinvested neighborhoods presents a tough, tough set of circumstances in which it can be hard to remain rational.

While many would dispute Milloy’s hyperbole, he was nonetheless expressing the sentiments of a substantial part of the city's electorate. The return of middle-class whites to once-disinvested neighborhoods presents a tough, tough set of circumstances in which it can be hard to remain rational.

My own belief is that we should be working for revitalization that encourages mixed-income neighborhoods in which new residents and businesses are welcomed while displacement is avoided or minimized. But make no mistake: that revitalization must continue to take place in America’s cities. It is absolutely essential if we are to have any hope of a more sustainable tax base to fund civic restoration and improvement, a more equitable civil society, and a more environmentally sustainable pattern of growth that reduces sprawling consumption of the landscape while bringing our rates of driving emissions down (central locations with moderate or greater density and nearby conveniences facilitate walking, transit, and shorter driving distances).

Regular readers may recall that I have a few favorite examples of neighborhoods that seem to be revitalizing in the right way: for example, the LEED-ND certified Melrose Commons in the South Bronx; Old North Saint Louis; and Boston’s Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative. In each of these, existing residents are fully committed to their community’s revitalization and to shaping rather than opposing it. All are achieving levels of success, though the national real estate slump of the last several years hasn’t helped any.

The truth is that what some badly disinvested cities, districts, and neighborhoods desperately need is some form and degree of ‘gentrification.’ The challenge is to have enough without having too much.

The truth is that what some badly disinvested cities, districts, and neighborhoods desperately need is some form and degree of ‘gentrification.’ The challenge is to have enough without having too much.

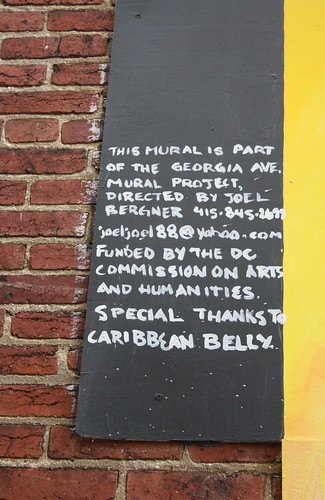

On that point, and also here in DC, Jeremy Borden recently wrote in The Washington Post that residents have formed a community development task force to influence the shape of development along our city’s Georgia Avenue corridor, a major north-south thoroughfare. Lined with mostly smaller storefronts and mid-rise older buildings, Georgia Avenue was once the scene of mass riots and crime but now is poised for an update. A historic theater is being restored and a new, mixed-use development under construction will house, among other tenants, The United Negro College Fund. Kent Boese reported last year on the Greater Greater Washington blog that, for its part, the city is contributing an $8 million “Great Streets” infrastructure upgrade, which will improve and replace sidewalks, install new trash cans and park benches, install “historically sympathetic” street lighting and signals, create textured crosswalks, improve two parks and install green infrastructure to manage stormwater.

Several important new projects are also on the table, including major redevelopment on the site of the famous but recently closed Walter Reed Army Medical Center; a campus plan for Howard University, along with the nearby Howard Town Center development; and a controversial Walmart.

The Georgia Avenue Walmart, one of four likely to be built in DC, could unfortuntely pose a threat to just the kinds of businesses that the city and residents are hoping to attract and support. An economic impact analysis prepared by Public and Environmental Finance Associates and filed with the city found that “there is every reason to anticipate” that the store “will cause substantial diversion of sales from existing businesses in . . . immediate and nearby neighborhoods, and from elsewhere in the District,” particularly increasing the probability that existing supermarkets could close as a result of lost business. (The report does not appear to be online, but I was furnished with a copy.) Nonetheless, the city’s planning office has found the proposal “not inconsistent” with the city’s comprehensive plan, and is allowing the massive store to go forward, apparently concluding that economic impact is not an issue the office was allowed to consider in the review process.

In other words, if citizens really want a community-oriented process for revitalization, they need the city to fix the planning and zoning process pronto.

More hopeful for Georgia Avenue, perhaps, is a report that the city is considering building the corridor’s new streetcar line, which had been back-burnered, sooner rather than later. In the meantime, the community development task force has created a history trail and is sprucing up blank walls with murals and empty storefronts with art projects. The idea is to bring a sense of pride and progress that will make the neighborhood more pleasant while helping to attract the right kind of investment. “We do want new people along Georgia Avenue,” one of the task force leaders told Borden, “But we want to make sure that the people who want to stay can stay and shape Georgia Avenue in the way we want.” I'm hoping that the task force will be a strong, responsible, and influential voice as new businesses and people come to the corridor.

Even at best, though, revitalization can be messy, as well as dependent on the legal framework and economic context in which opportunities are presented. And the reality is that the “middle class, mostly young whites” disparaged in Courtland Milloy’s election gloating are going to be critical to any urban resurgence. In his always-thoughtful blog Rebuilding Place in the Urban Space, Richard Layman describes some of the reasons:

“[F]or the past 20 years . . . DC's black population has been dropping--in large part as the black middle classes decamped to the suburbs, abandoning the city, just as the whites had done in the 1950s.

“If not for an influx of white and Hispanic residents, DC's population would have steadily declined over the past 20 years because of black outmigration.”

While I haven’t researched the numbers to discern the extent to which Washington’s changing demographics reflect those of other cities, I think they suggest a truth likely to be universal:  We need cities capable of attracting new residents with incomes that can strengthen the tax base and support new economic activity, while at the same time being strong and hospitable enough to hold on to existing residents. And we must provide both groups with the services and amenities required to meet their needs. Is that too much to hope for? I think that getting there is going to be a rough and rocky road, but I am optimistic for the long run.

We need cities capable of attracting new residents with incomes that can strengthen the tax base and support new economic activity, while at the same time being strong and hospitable enough to hold on to existing residents. And we must provide both groups with the services and amenities required to meet their needs. Is that too much to hope for? I think that getting there is going to be a rough and rocky road, but I am optimistic for the long run.

Fashioning the more equitable, prosperous, and sustainable cities of the future will require more, not less, revitalization and more, not fewer, new residents. But it will also require providing high-quality affordable housing in neighborhoods where revitalization is occurring. It will require bringing existing residents to the table early and often in the planning process, but to help shape good neighborhood development, not to prevent it. And, where wounds over gentrification exist, we must take steps to heal them, because divisive rhetoric only hurts everyone involved and, ultimately, the viability of our communities.

Move your cursor over the images for credit information.