Report highlights exemplary clean water practices in Philadelphia, Milwaukee, other cities

Posted November 17, 2011 at 1:17PM

In a major report released yesterday, my colleagues at the Natural Resources Defense Council outlined challenges and solutions facing US cities in restoring and maintaining the quality of rivers, lakes, and other waterways.

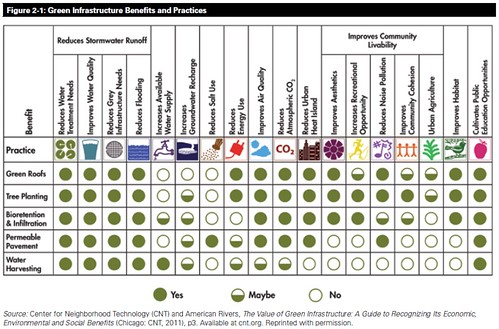

The report, Rooftops to Rivers II, strongly supports the use of green infrastructure – vegetation and other water collection and filtration systems that absorb rainfall before it becomes polluted runoff – to protect watersheds. The federal EPA estimates that currently more than 10 trillion gallons of untreated urban and suburban runoff makes its way into our surface waters each year, degrading recreation, destroying fish habitat, and altering stream ecology and hydrology. The problem becomes particularly acute in cities that drain both stormwater and sewage into a common set of pipes and conveyances. When major storm events prove more than these frequently older systems can handle, the result is “combined sewer overflows,” a noxious mess.

The new report builds on an earlier Rooftops to Rivers report published by NRDC in 2006.

I am a strong supporter of green infrastructure, and not just because of its water quality benefits. We desperately need more cities and suburbs with a critical mass of buildings and people – walkable densities – to conserve the natural and rural landscape outside of cities and to reduce transportation emissions and the costs of extending infrastructure. We need to reduce sprawl by taking advantage of opportunities to build on vacant lots in existing communities. That is the essence of smart growth.

I am a strong supporter of green infrastructure, and not just because of its water quality benefits. We desperately need more cities and suburbs with a critical mass of buildings and people – walkable densities – to conserve the natural and rural landscape outside of cities and to reduce transportation emissions and the costs of extending infrastructure. We need to reduce sprawl by taking advantage of opportunities to build on vacant lots in existing communities. That is the essence of smart growth.

But we also need to bring nature into our city environments, both to maintain ecological health and to enrich the health and well-being of city residents and visitors. Green infrastructure makes urban density better and more inviting by doing exactly that with trees, green roofs, gardens, natural landscaping, and more.

Rooftops to Rivers II examines in detail case studies from around the country (plus one in Canada):

“[The report] provides case studies for 14 geographically diverse cities that are all leaders in employing green infrastructure solutions to address stormwater challenges -- simultaneously finding beneficial uses for stormwater, reducing pollution, saving money, and beautifying cityscapes. These cities have recognized that stormwater, once viewed as a costly nuisance, can be transformed into a community resource. These cities have determined that green infrastructure is a more cost effective approach than investing in ‘gray,’ or conventional, infrastructure, such as underground storage systems and pipes. At the same time, each dollar of investment in green infrastructure delivers other benefits that conventional infrastructure cannot, including more flood resilience and, where needed, augmented local water supply.”

Each of the locations was evaluated with respect to six key actions:

- Long-term planning for green infrastructure

- Stormwater retention standards

- Use of green infrastructure in comprehensive land planning

- Private sector incentives to install green infrastructure

- Guidance and assistance

- Long-term funding to support green infrastructure investment

Of the cities studied, only Philadelphia was found to be exemplary in all six categories. But five other cities were found praiseworthy with respect to all but one of the categories (the deficiency varied from one location to another).

I’ve referenced Philadelphia before for its green initiatives, and my colleagues are clearly impressed with what they have observed there:

“Over the next 25 years, Philadelphia is committed to deploying the most comprehensive urban network of green infrastructure in the United States. Philadelphia’s Green City, Clean Waters plan, recently approved by state regulators, requires the retrofit of nearly 10,000 acres (at least one-third of the impervious area served by a combined sewer system) to manage runoff on-site; relies on green infrastructure for a majority of the required CSO reductions; calls for the investment of more public funds in green infrastructure (at least $1.67 billion) than in traditional gray approaches; and leverages substantial investments from the private sector, primarily through application of a one-inch retention standard for new development and redevelopment projects citywide.”

Philadelphia also impressively offers a package of regulatory and financial incentives to private property owners to install green infrastructure, along with demonstration projects and reference manuals.

Other cities rating very well (if imperfectly in varying aspects) include Milwaukee, New York, Portland, Syracuse, and Washington, DC. With respect to Milwaukee, for example, the city has adopted practices to eliminate combined sewer overflows; dedicated capital funds to support green roofs, rain barrels and rain gardens; and published an online cost-benefit tool for green infrastructure. The city also has a program “to purchase and restore land upstream of Milwaukee to prevent flooding and overflow problems from occurring in the first place.” Only Milwaukee’s lack of a regional green infrastructure plan kept it from being rated highly in all categories.

My colleagues caution that, even for the locations that are rated well in most categories, the shortcomings can be critical. In New York City, for example, NRDC and a range of business and nonprofit partners are urging the city to adopt a regulatory standard for stormwater management on all new development. NRDC’s water program attorney Larry Levine, based in New York City, says that “stopping runoff with green infrastructure on private property is a crucial part in the solving the city’s stormwater problems and improving the health of our communities.”

Apart from the report, a story by Darryl Fears in today's Washington Post indicates that Washington, DC, is employing a strategy that combines 13 miles of new, underground "gray" pipes with above-ground vegetative approaches. DC Water’s general manager, George Hawkins, has asked the federal EPA’s permission to spend $10 million "to place grass on rooftops, put flower gardens at curbsides, and lay sidewalks made of porous stone."

NRDC's Rebecca Hammer told Fears that green infrastructure brings community benefits but also suggested that its stormwater benefits may need to be fully proved. “Assuming they can stop the same number of sewer overflows, we would be very supportive,” she told Fears. The new underground pipes will cost $2.6 billion, paid for by a major rate increase to home and business owners.

In addition to profiling the case studies, the report outlines a set of policies to accelerate adoption of the six key green infrastructure strategies across the country.

Other communities highlighted in the report include Aurora (IL), Toronto, Chicago, Kansas City (MO), Nashville, Seattle, Pittsburgh, and the Rogue River watershed (MI). All are implementing one or more of the key strategies. Additional cities discussed, but in less detail, include Indianapolis, Cleveland, Cincinnati, Minneapolis, Jacksonville, and Tucson.

Although land use strategies were beyond the scope of Rooftops to Rivers II, and are not discussed in it, smart growth too can play a very important role in protecting watersheds from stormwater runoff. The authors observe that, under current trends, the US could have 68 million more acres of developed land, with accompanying roads, parking lots and rooftops that promote runoff, by 2025. But that need not be the case: more efficient land use can bring that number down.

The federal Environmental Protection Agency, for example, has conducted research demonstrating that for new development even modest increases from sprawl-type densities can help reduce the expansion of impervious surface across watersheds:

- “The higher-density scenarios generate less storm water runoff per house at all scales — one acre, lot, and watershed — and time series build-out examples;

“For the same amount of development, higher-density development produces less runoff and less impervious cover than low-density development; and

“For the same amount of development, higher-density development produces less runoff and less impervious cover than low-density development; and- “For a given amount of growth, lower-density development impacts more of the watershed.”

In a separate report exploring the particular vulnerabilities that apply to coastal communities – coastal counties are home to 52 percent of US population and continue to grow –

the Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, reached a similar conclusion:

“Through smaller building footprints for new construction, reuse of existing buildings, and creative solutions to parking, compact building design can leave undeveloped land to absorb rainwater, thereby reducing the overall level of impervious surface in the watershed. Together, compact community and building design techniques reduce runoff, flooding, and stormwater drainage needs, contributing to better watershed health. For waterfront communities dependent on the health and beauty of neighboring waters, these outcomes are vital.”

NRDC supports both sets of strategies – the ones highlighted in the report and smart growth – to address our nation’s formidable water quality challenges. It is really encouraging to see that my colleagues – whom I know to be a demanding bunch – are finding some exemplary practices to highlight in a diverse range of communities. To learn more about Rooftops to Rivers II, go here.

Move your cursor over the images for credit information.