The environmental building blocks of urban happiness

Posted February 2, 2012 at 3:05PM

As regular readers may remember, I am fascinated by the relationship of our cities, and the way they are configured, to our mental and emotional well-being. The relationship of urban form to physical health is finally getting some of the attention it deserves, but how the shape of our communities and neighborhoods affects mental health and the much more elusive concept of happiness remains under-explored.

New research, however, provides some intriguing clues. In particular, a fascinating study authored by a team from West Virginia University and the University of South Carolina Upstate, and published last year in Urban Affairs Review, examined detailed polling data on happiness and city characteristics from ten international cities. In an article titled “Understanding the Pursuit of Happiness in Ten Major Cities,” the authors concluded that good urbanism contributes positively to happiness:

“We find that the design and conditions of cities are associated with the happiness of residents in 10 urban areas. Cities that provide easy access to convenient public transportation and to cultural and leisure amenities promote happiness. Cities that are affordable and serve as good places to raise children also have happier residents. We suggest that such places foster the types of social connections that can improve happiness and ultimately enhance the attractiveness of living in the city.”

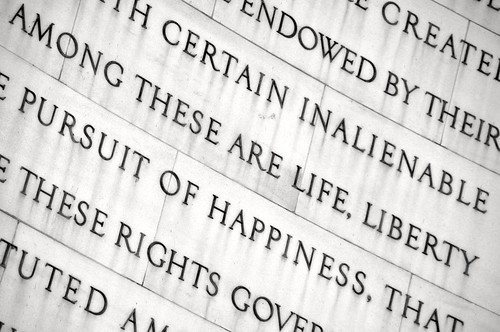

As I noted last June, in the US “the pursuit of Happiness” is listed in the first sentence of our Declaration of Independence, right alongside life and liberty as a coequal “inalienable Right” of all people.  That’s a lofty dose of respect from the founders of our republic. Shouldn’t it get the same respect from those of us in the business of pursuing environmental quality? Trust me: it doesn’t.

That’s a lofty dose of respect from the founders of our republic. Shouldn’t it get the same respect from those of us in the business of pursuing environmental quality? Trust me: it doesn’t.

There are a lot of reasons why this is so, but surely one of them is that happiness is viewed by just about everyone outside the mental health field as highly subjective. And it is certainly difficult to measure. The effect of environmental factors on happiness is more difficult still, notwithstanding some intriguing efforts in the country of Bhutan and the cities of Victoria, Seattle, and Bogata. The concept of “healing cities,” which I profiled recently, also appears to be on the case, taking a holistic view of health that includes “physical, emotional, mental, social and spiritual needs.”

The new academic study, kindly forwarded to me by Kevin Leyden, one of its authors, attempts to approach the subject with scientific rigor. Leyden and his colleagues believe that city attributes do indeed make a difference and that, as a result, “happiness and its pursuit . . . is a subject that should be of concern to scholars of urban places and urban policy.”

Of course, city aspects are not alone in influencing happiness, and neither Leyden nor I would claim otherwise. Leyden cities a “Big Seven” group of factors recognized by prior research as most substantially affecting adult happiness: wealth and income (especially as perceived in relation to that of others); family relationships; work; community and friends; health; personal freedom; and personal values.

The researchers drew from an extensive “quality of life” survey undertaken by Gallup in 2007 for the government of South Korea and published in 2008. Approximately 1,000 people were surveyed from each of ten cities: New York, London, Paris, Stockholm, Toronto, Milan, Berlin, Seoul, Beijing, and Tokyo. Respondents self-reported their overall degree of happiness (measured on a scale of 1 to 5) along with their degree of agreement with a range of statements designed to tease out additional factors.

Leyden’s team examined the findings, looking for statistically significant correlations. They found confirmation of the Big Seven factors, but also variations that could not be explained by the Big Seven. Examining additional findings from prior research along with data from the Gallup study, they concluded that a feeling of connectedness was a key factor in predicting happiness, and posit that the extent to which urban design fosters – rather than inhibits – that feeling may be an important additional determinant of happiness:

“Do connections with place affect happiness? Does the design of the city and its neighborhoods and the way those places are maintained have an effect on happiness? . . .

“We hypothesize that the way cities and city neighborhoods are designed and maintained can have a significant impact on the happiness of city residents.

The key reasons, we suggest, are that places can facilitate human social connections and relationships and because people are often connected to quality places that are cultural and distinctive. City neighborhoods are an important environment that can facilitate social connections and connection with place itself . . .

“But not all neighborhoods are the same. Some are designed and built to foster or enable connections. Other are built to discourage them (e.g., a gated model) or devolve to become places that are antisocial because of crime or other negative behaviors. Increasingly, researchers and practitioners have become aware that some neighborhood designs appear better suited for social connectedness than others.”

The Gallup study examined a number of questions directly related to the built environment, including the convenience of public transportation, the ease of access to shops, the presence of parks and sports facilities, the ease of access to cultural and entertainment facilities, and the presence of libraries. All were found to correlate significantly with happiness, with convenient public transportation and easy access to cultural and leisure facilities showing the strongest correlation.

The statistical analysis also included questions related to urban environmental quality apart from cities’ built form, and produced additional significant correlations:

“The more respondents felt their city was beautiful (aesthetics), felt it was clean (aesthetics and safety), and felt safe walking at night (safety), the more likely they were to report being happy.

Similarly, the more they felt that publicly provided water was safe, and their city was a good place to rear and care for children, the more likely they were to be happy.”

Among these, the perception of living in a beautiful city had the strongest correlation with happiness. Curiously, though, the researchers found that the perception of "clean streets, sidewalks, and public spaces" actually had a somewhat negative association with happiness. Happy people apparently find their urban environments both beautiful and messy. (Well, the survey did include New York.)

Statistics geeks will find much to pore over in this intriguing and meticulously reported study. I find that it provides empirical strength to those of us who believe that “the environment” is concerned not just with traditional pollution or land conservation (both of which remain important) but also with what and where we build; and not just with parts per billion of this or that but also with the quality of human relationships and well-being. I believe the authors of the Declaration of Independence would agree.

Related post: Why We Love the Places We Love

Move your cursor over the images for credit information.