Nashville's promise for a greener transportation future

Posted February 15, 2012 at 1:31PM

The regional planning authority for the Nashville, Tennessee metropolitan area has embarked on a new philosophy to put the notoriously sprawling region on a less polluting and less consumptive path, anchored by walkable neighborhoods, public transportation, and maximizing the efficiency of current roadways. Meeting the laudable goal of shaping a more sustainable region will not be easy: in 2001, the Nashville metro area was cited as the nation’s most spread-out – the area with the fewest number of residents per square mile – in a review of 271 of our largest metro areas.

If Nashville’s land use challenge is daunting, its transportation challenges – in large part created by the predominance of sprawl – are similarly formidable. The nonprofit organization Cumberland Region Tomorrow highlights some of the statistics:

- The Nashville region ranks near the bottom, 93 out of 100 among major metro areas, for transit access.

- The average commuter drives 37 miles per day.

- The Region was ranked number one in a 2011 report for the most hours spent in rush hour traffic per person.

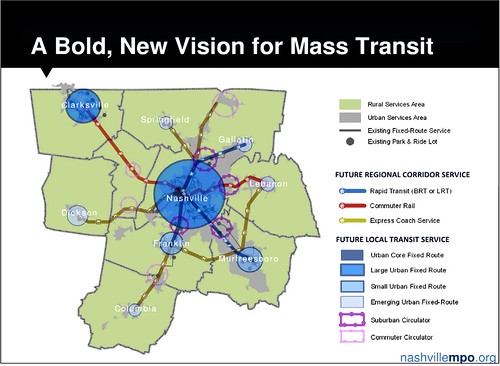

The Nashville area Metropolitan Planning organization, which has spent years building support and a detailed transportation planning framework for a greener, healthier region around the Music City, deserves major credit for its new vision.

Under federal transportation law, responsibility for planning transportation investments assisted by federal funds – which includes most new or expanded transit service and just about all roads other than those that are purely local – is assigned to multi-county (and in a few border areas multi-state) metropolitan planning organizations. For the Middle Tennessee area including and surrounding Nashville, the state’s largest city, it is the Nashville MPO that plans how transportation dollars will be spent, and what new facilities, if any, will be built. In the US, this is as close to a true regional growth planning framework as we usually have.

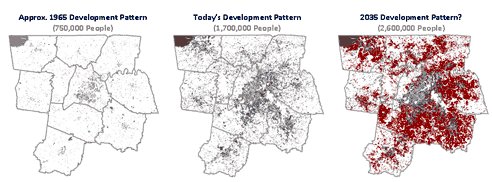

If Nashville were to continue the course of recent decades, the results would not be pretty: the maps above show the developed area of the region in 1965, in 2009 and, if there is no change from past trends, in 2035 as the region adds an expected 900,000 more people, a 53 percent increase. A comparative analysis by Cumberland Region Tomorrow (see slide 91) estimated that, without a change in investment philosophy, the region would be required to spend almost $7 billion for road construction and other infrastructure, compared to $3.4 billion under a more carefully planned scenario; would spread 62,000 additional acres of pavement and other impervious surface around regional watersheds, rather than “only” 35,000; and develop a whopping 365,000 additional acres of currently rural land, as compared to 91,000 acres under a more carefully planned scenario.

I was first exposed to the new, 25-year Nashville region transportation plan as a jury member asked to review candidates for a national smart growth award. I was impressed. I am now teaching a law school seminar on sustainable communities and decided to take a closer look to see whether the region's new vision might be an appropriate case study for our class. I’m still impressed.

Particularly striking are the plan’s “major objectives,” which include the following:

Adopt a “fix-it-first” approach that emphasizes maintenance and improvement of existing facilities (in other words, ensure that current roads are repaired and maintained before building new ones).

Adopt a “fix-it-first” approach that emphasizes maintenance and improvement of existing facilities (in other words, ensure that current roads are repaired and maintained before building new ones).- Shift investment strategies toward a diversity of transportation modes, rather than focusing solely on roadway capacity.

- Encourage the development of context-sensitive solutions “to ensure that community values are not sacrificed for a mobility improvement.”

- Increase efforts to improve transportation corridors so they contribute to sense of place.

- Invest in walkable communities that offer citizens the ability to access their needs without relying on automobiles.

- Invest in a modern regional transit system.

- Work to ensure that Middle Tennessee is considered in plans for high-speed intercity rail service.

There are other objectives, but they are very consistent with these.

Even better, the plan adopts a 100-point scoring system with which to evaluate new transportation proposals. The evaluation criteria include nine categories, and the three that are given the most weight (15 points each), relate directly to sustainability:

- System preservation and enhancement (including fix-it-first and context-sensitive approaches)

“Quality growth, sustainable development, and economic prosperity” (including whether the project supports infill and/or redevelopment within existing developed areas, is located near mixed-use and high-density areas [such as The Gulch, Nashville’s first LEED-ND-certified development], corrects stormwater drainage concerns, and is located near existing jobs)

“Quality growth, sustainable development, and economic prosperity” (including whether the project supports infill and/or redevelopment within existing developed areas, is located near mixed-use and high-density areas [such as The Gulch, Nashville’s first LEED-ND-certified development], corrects stormwater drainage concerns, and is located near existing jobs)- Multi-modal options (such as transit service, bicycle facilities, and pedestrian improvements and amenities)

A fourth category, “health and environment” (10 points) also relates directly to sustainability. It evaluates whether a proposed project improves accessibility for low-income and minority communities, the disabled, and the aging; whether the project promotes physical activity, reduces miles or hours driven, or vehicle emissions; and whether it is located close to environmentally or culturally sensitive areas (if so, points are subtracted in the evaluation).

For a transportation plan, and a guiding philosophy for allocating transportation investment, that’s pretty darn good in a place that has been called one of the most sprawling and congested (and, in some reports, the most sprawling and congested metro area) in the country. The proof, as always, will be in the actual decisions made on the ground. But this is fantastic guidance for planners and citizens alike to measure those decisions against.

Move your cursor over the images for credit information.