Citizen participation in the design of sustainable communities

Posted May 16, 2012 at 1:29PM

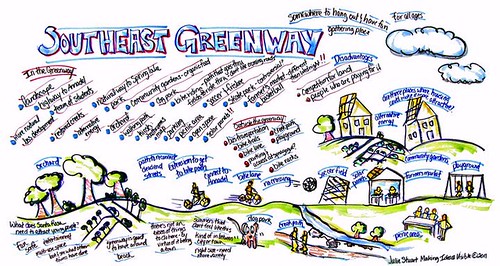

(Illustration courtesy of Julie Stuart, Making Ideas Visible)

Today’s post is guest-authored by my friend and frequent collaborator, Lee Epstein. Lee is an attorney and land use planner working for sustainability in the mid-Atlantic region.

First, a confession: I went to urban and regional planning graduate school during the “horse and buggy” days, or so it seems today. We read hard-cover books about planning theory and practice. In our urban design studios, we hunched over drafting tables clutching our T-squares late into the night (really). We weren’t unrolling parchment in caves, but it was pretty darned close.

We used hand-held calculators for simple data crunching, and for running multiple regression analyses, we walked over to the small “computer lab.” This was a dingy, cramped room peopled mostly by pallid, red-eyed math and engineering grad students who were fueled solely by caffeine and an occasional pizza, and who looked like they never saw the light of day. There we created shoe boxes full of punch cards, and waited in line to get them processed by the two large computers which, after processing our hundreds of cards, spit out the results on yards of un-spooling track paper (the kind with holes on both sides to track through the printer).

We also used large, hard-copy maps, and for a really innovative approach, overlaid them with clear acetate that showed different landscape features or attributes. My 200+ page Master’s Thesis was prepared using a “word processor,” just a step up from an electric typewriter.

Fond memories? Not so much, but it was an “experience.”

There were no laptops or desktop personal computers. None of the wonders of GIS or GPS systems. No 3-D, fly-through designs. No e-mail. No smart phones or text-messaging. No Facebook or Twitter. No Google Earth. No blogs (!).

The old and new ways of citizen engagement

But along with theory, policy and design in grad school, we learned about citizen participation being a very important part of planning. Mostly, what citizen participation meant then was being sure to hold enough public meetings about a new plan to get some public input on it. These would be advertised in the local newspapers, and once you got through the meetings and made changes or adjustments, you moved on to the next phase of the “rational planning process.” These meetings weren’t always quiet, and “rational” sometimes got lost along the way, but still, this was all pretty straightforward.

Well, Toto, we’re not in Kansas anymore.

The electronic communications and high-tech, computing revolutions have changed planning for the better since the 1970’s and 1980’s. The tools available today are powerful and much more effective at analyzing, arraying, and mapping important data. Laptops put into our hands the power of big, furnace-sized computers from a couple of decades ago. We can run alternative growth scenarios in real time right on those laptops, and model their impacts on local government budgets, water or air quality, or affordable housing. We can play with building designs, or bulk and density, how to manage stormwater runoff, and see what these designs might look like in a particular place. And we can obtain, view and analyze mapped information on hundreds of different parameters, depending upon the technical capacity of a particular state and region or what’s available from the feds.

Along with our data-crunching capabilities, our communication capabilities have also vastly improved. Using those scenario-planning programs in real time, in a public meeting, is a great way to engage local officials and citizens alike, and a good way to present hard choices on this or that policy option or direction with respect to sustainability. Publishing GIS maps on-line, so citizens can see where the forest ends and subdivisions begin, the march of sprawl over time, the health of local streams, or how sea level rise is affecting coastal and estuarine communities, all helps visually communicate concepts that may be difficult to understand in the abstract.

Not just feedback but collaboration

This all means that public participation in planning, growth, and sustainable design decisions has already changed in many localities – and that there is no excuse for it not changing everywhere soon. Bringing the public into public policy decision-making is no longer a matter of the “one-and-done”: you hold a public hearing on a development proposal, take testimony (that is, if anyone shows up to give it), and make the decision (informed or not informed by the testimony). It’s not even any longer a matter of a year-long series of in-person meetings by a local volunteer stakeholder committee. Now we can have meetings via the web, so even stay-at-homes can regularly participate. And we can bring into that process the sorts of whiz-bang analytic tools mentioned above, that can make difficult to understand concepts instantly understandable.

Better yet, now there are a slew of ways for not regularly talking to people, but rather connecting, communicating -- interacting – with them: making connections via social networks or a list-serve is one way, for example, to engage citizens in an on-going conversation concerning local policy. Communicating through the local government’s website, or by regular contributions to, or comments on a blog, through RSS feeds, or again, in real time, via Twitter, about the latest change in that big new development proposed for the corner of Main and First Streets, are among the ways citizens today can become a more vital part of the process.

Better yet, now there are a slew of ways for not regularly talking to people, but rather connecting, communicating -- interacting – with them: making connections via social networks or a list-serve is one way, for example, to engage citizens in an on-going conversation concerning local policy. Communicating through the local government’s website, or by regular contributions to, or comments on a blog, through RSS feeds, or again, in real time, via Twitter, about the latest change in that big new development proposed for the corner of Main and First Streets, are among the ways citizens today can become a more vital part of the process.

All that new give and take is mostly good news when it comes to citizen participation. There’s some “bad” news that comes with it, however, though mostly that’s really just part of living in a democratic society. What nearly instantaneous communication has given us is not only the ability to dig into an issue pretty quickly, but also to react with our appointed and elected officials – and organize ourselves – without much knowledge, in ways that are not so very useful.

We’ve seen some of this of late with the “Agenda 21” crowd, which this blog and others (notably, this thoughtful article by Ben Brown) have addressed previously. These folks, fearful and suspicious about a massive, world-wide government conspiracy to “take away our freedom,” have in some places and on some occasions made a naturally messy process into an untenable and even dangerous one. What is always fine, and indeed, most welcome in good urban planning, is a rich mix of contrasting ideas competing for relevance. Different views about this or that project, whether a specific direction will best advance the community’s overall welfare and sustainability, are what make planning in a democratic society work. People marshalling the data and facts to support their point of view and serving it up to others to debate and choose a direction in which to head is what planning should be all about. Unfortunately, Agenda 21 folks, alerted to an open planning meeting via Twitter or e-mail or an anti-planning blog, sometimes show up not to participate but merely to shout down public officials or their fellow citizens, disrupting an open process to destroy, rather than contribute to it. That’s hijacking democracy, not practicing it.

Empowering us to discover what we really want

Not everyone will agree that a particular urban design is one that can stand the test of time; that “X” amount of density is the right amount for animating a residential/commercial area; that one good way to achieve “walkability” is by slowing traffic in a particular place; or that the local jurisdiction should act to conserve its working farmland and help its farmers keep farming, so that future generations can live in a place where town and country mixes effectively. Green growth and sustainability are sometimes tough concepts to wrap one’s head around.

Not everyone will agree that a particular urban design is one that can stand the test of time; that “X” amount of density is the right amount for animating a residential/commercial area; that one good way to achieve “walkability” is by slowing traffic in a particular place; or that the local jurisdiction should act to conserve its working farmland and help its farmers keep farming, so that future generations can live in a place where town and country mixes effectively. Green growth and sustainability are sometimes tough concepts to wrap one’s head around.

The new communication tools available to us in 2012 should enable us to do just that – communicate better about what we want as a society, learn about an issue or concept, and participate, really and truly participate and debate, in the decision-making of our government. That’s really the only way to obtain some mutual understanding of what sustainability means to a community. And it’s really the only way to get to a state of sustainable growth and design around which a community can rally.

Pry that old T-square out of my cold, dead hands? Please?

Related posts:

- Want to build development that the community will welcome? Ask them what they want. (April 16, 2012)

- The citizen as expert: grassroots planning Down East (January 6, 2012)

- Can grassroots planning save what's best of a rapidly suburbanizing community? (December 9, 2011)

- Warning: black helicopters on the horizon (or so they say) (by Lee Epstein, March 23, 2011)

- 5 ways that local groups and citizens can use LEED-ND (January 24, 2011)

Move your cursor over the images for credit information.

Lee Epstein most recently contributed to this blog on March 21, 2012 (“Will the real green colleges please stand up?”).

Please also visit NRDC’s sustainable communities video channel.