From elephant to estuary: does the 2013 European Green Capital have something to teach US cities?

Posted December 17, 2012 at 5:45PM

The city of Nantes, the fifth largest in France, sits on the estuary where the storied River Loire begins to meet the Atlantic Ocean on that country’s northwestern coast. It is a place of rich history dating back at least as far as the second century, and subsequently including the Dukes of Brittany in the late middle ages and, in the 18th century, the famed novelist and futurist Jules Verne. Economically Nantes was long a port and shipbuilding center of considerable significance.

But the shipping and shipbuilding industry in western Europe began a serious decline in the 1960s and 1970s, and most of what survived – or, in some cases, expanded – on the Loire was established in the port of St-Nazaire some 50 kilometers (32 miles) to the west of Nantes. The last major shipbuilding facility in Nantes closed in 1986.

The Green Capital designation

The proud city needed a new identity in order to remain relevant. That new identity became, first, culture and then, sustainability. Today the two have come together in some highly innovative ways that have led the European Union to designate Nantes as its “Green Capital” for 2013.

The EU’s annual green designation was created by the European Commission in the last decade, with Stockholm selected as the first honoree, for 2010. The prestigious competition involves a lengthy application process and is judged on the basis of twelve overlapping environmental criteria:

- Response to climate change

- Transportation

- Urban green spaces

- Land use

- Nature and biodiversity

- Air quality

- Noise pollution

- Waste reduction and management

- Water consumption

- Wastewater treatment

- Green municipal management

- Dissemination of best practices

The 2013 award for Nantes included specific praise for the city’s efforts regarding climate, transportation, water, and biodiversity.

Last year I wrote about Hamburg, the 2011 Green Capital and another port city that, among other things, is greening its shipping operations, undertaking major green redevelopment projects, and knitting some of its parts back together by capping a major freeway. The green baton was then passed to the Basque city of Vitoria-Gasteiz for 2012. After Nantes, in 2014, it will reside in Copenhagen.

Building a green civic brand

The Nantes metropolitan area, which enjoys some common regional governance, comprises 24 municipalities and 600,000 current residents. The population is projected to grow by another 100,000 by 2030.

Nantes has adopted a climate action plan with a goal of reducing carbon dioxide emissions by 30 percent (compared to 1990 levels) by 2030. It has also become a leader in the international discourse for climate concerns, heading a worldwide coalition of cities participating in climate negotiations at the United Nations and co-chairing (with Copenhagen) a working group of major cities in Europe dealing with climate concerns. The city has a staff of fifteen (full-time equivalents) working on the implementation of its climate plan. That’s impressive for a population of 600,000.

In addition, Nantes was the first city in France to reintroduce trams (streetcars and light rail) as a modern form of public transit and claims the third busiest transit system in the country. By 2015, the entire transit system will be fully accessible to persons with limited mobility. The city also has a dedicated busway and an extensive bikesharing system.

In 1999, there was a transit stop within 300 meters (roughly a half fifth of a mile) of 80 percent of households in Nantes, already outstanding coverage compared to American cities; by 2009, that portion had increased to a very impressive 95 percent. Indeed, after decades of increasing automobile use, in 2001 and 2002 Nantes began to decrease the share of trips taken by solo driving, and a slim and increasing majority are now claimed by walking, transit, bicycling, and ridesharing. (That said, all may not be rosy with respect to transportation in Nantes. A new airport proposed for the outskirts has become sharply controversial.)

The Ile de Nantes project

One senses that the city is serious about establishing its green brand. Ecocity 2013, a world summit on sustainable cities, will take place in Nantes in September of next year, just after a World Green Infrastructure Congress organized by the French Association for Green Roofs and Facades. In October, there’s yet another major international green meeting, this time on wetlands. I counted six additional, large and environmentally themed meetings taking place in Nantes in 2013.

Compared to American cities, Nantes has much less sprawl and more green land outside the developed area. 62 percent of the region’s land base remains agricultural or natural. Yet there is evidence of sprawl: in the past 50 years, according to the regional agency Nantes Metropole, developed land has grown fifty percent faster than population. More about that soon.

All of this is on my mind because last week I was immensely fortunate to be among four other Americans invited by the French-American Foundation, the French Ministry of Culture, and the Maison des Cultures du Monde to visit Nantes and three other French cities to learn about ongoing efforts to promote urban sustainability in that country. While in Nantes, we were treated to tours and presentations of three outstanding green projects that give an impression of what the city is up to.

Major redevelopment in the city’s heart

Perhaps the most ambitious of these is the Ile de Nantes, the conversion of a 350-hectare (865 acres) industrial brownfield (more accurately, a conglomeration of brownfields) into an eco-district that will house 20,000 inhabitants in the heart of the city. (Located on an island in the middle of the Loire, the site could not be more unlike the lavish and renowned chateaux that lie upstream.) To the extent that Nantes is troubled by sprawl, there is no better antidote than redevelopment of underutilized land in the city’s center.

Until recently (and, to an extent, still) dominated by crumbling warehouses and rusted large machinery formerly used for shipping and shipbuilding, the project when complete will feature major cultural venues, a creative arts district, green demonstration projects, new tram and bus rapid transit facilities, a hospital, a large destination park, and walkable, mixed-use and mixed-income neighborhoods.

This project is big. Already completed or currently being constructed are 320,000 square meters (3.4 million square feet) of projects including 3,450 apartments, 135,000 square meters (1.5 million square feet) of commercial space, 42,000 square meters (452,000 square feet) of community facilities, and 38 hectares (94 acres) of public open space. Of the housing, 25 percent will be subsidized to be affordable, another 25 percent moderately priced, and the rest left to the market. And it’s going to get bigger: the work already committed and scheduled but not yet begun will roughly double those numbers.

The revitalized Ile de Nantes will include district heating and cooling, neighborhood composting facilities, an advanced waste management system, a cycling route around the island, and a photovoltaic power generation station. There’s a very cool creative-business incubator located in a vast building that once housed a go-kart rink. Features in operation intended to draw visitors to the island include quite a few for children, including an old-fashioned carousel on a towering platform and a giant, mechanical elephant that sometimes goes out for walks and has long been one of the city’s icons. (See short video below.) The scale of the project’s ambition is amazing.

Planning for ‘my city of tomorrow’

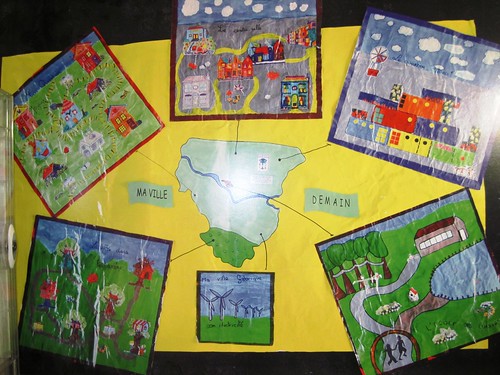

Ambitious in a different way is an extensive and creative process of civic engagement in determining a long-range vision for the metro region. Called Ma Ville Demain (“my city of tomorrow”) 2030 and launched in 2010, the project began with a sort of massive scoping process that solicited the “dreams, fears, hopes, views and questions” of residents through a variety of activities. Among them were questionnaires sent to every household in the 24 municipalities, around a hundred community meetings and presentations, and a website where citizens could post their aspirations and concerns. The organizers sought input on nine key questions relating to (roughly translated) the region’s economy, climate issues, employment, spatial growth, identity, social fabric, individualism, communication, and innovation. Some 12,000 residents participated, contributing more than 1,500 proposals and concepts.

The locals like what they see in their city: over 80 percent of those who answered the questionnaire believe that the Nantes metro region is “developing well in economic and cultural terms,” according to Nantes Metropole. Regular readers of my writing may chuckle at what I am about to report, given my attempt to ban the overused word “vibrant” and its close relatives from my vocabulary, but the agency also reports that “vibrancy is the 4th symbol most frequently cited by local inhabitants” to characterize the region, after the more visible and physical symbols of the river, the castle of the Dukes of Brittany and the famous mechanical elephant.

Among the residents’ expressions were desires for Nantes to become more international, to seize upon its sectors of creativity and innovative technology, and to capitalize upon and expand its lively public spaces. Participants also stressed a need for more robust systems for renewable energy, “third spaces” of serendipitous congregation in every neighborhood, and a local and self-sufficient economy. Planners distilled the contributions into three (somewhat, but not completely, alternative) broad visions:

- Pursuing excellence at home and abroad. This vision stresses an internationally relevant business environment, along with efficient land use and transportation. One of the subheadings is “a dense and concentrated city surrounded by nature and relationships with other regions.”

- Investing in innovation and creativity. With apologies to my friend Richard Florida, this vision seems very much built around a French version of his “creative class” concept: it is fundamentally about attracting talent, fluid career paths, and a future built around innovation. “Nature in the city is dispersed and evolving.”

- Building on local resources and local empowerment. If the second vision is Richard Florida’s, then the third can be linked with James Howard Kunstler. It’s about local agriculture, energy efficiency, clustering, jobs close to home, and “mutual assistance and solidarity.” The region as a whole is less important than smaller geographies in this scheme.

Our team visited a sort of interactive laboratory where citizens can view some diagrams based on these ideas and various combinations of them. The most fun was a sort of computer game that allows users to choose among various answers to basic questions about land use, transportation, economy and so forth, and see what happens when one combines disparate and sometimes conflicting choices. It was elementary but really imaginative. (Years ago Eliot Allen and I played around with something similar for NRDC’s website, but of course lost momentum when the specter of Getting Something Done on Our Website Without Significant Funder Support reared its ugly head. Actually, we ended up doing Picturing Smart Growth instead, which I am still proud of.)

Late last week the planners in Nantes released a synthesis of all the community input into a single visionary framework that relates the ideas to each other and contains a little something for everyone. I don’t mind that it does, by the way: if including a little something for everyone increases shared community ownership of the vision, that will be a great thing. And I actually envy the planners if they get to translate the vision into a regional land use plan. (But that’s why the editors at The Atlantic Cities frequently refer to me as an “urban wonk.”)

Using art to reveal the estuary

My favorite – and certainly the most creative – of the concepts our team was shown in Nantes is a project called Estuaire. This ambitious and striking exhibit has placed large-scale, provocative public art projects along the banks of the Loire inside and between Nantes and St-Nazaire, as a way of drawing interest to the many benefits of the estuary, environmental and otherwise:

“As the years go by, the Nantes Saint-Nazaire metropolis grows with the ambition to become the economic and cultural hub of the West of France region, on a European scale. Asking artists to create works, within cultural places of Nantes and Saint-Nazaire but also on the estuary banks, linking these two cities, playing with the landscape or braving it, fitting into it or standing out of it, acknowledging the size of the area and its diversity, “Estuaire” (Estuary Event) helps build the identity of this metropolis.

“Permanent or temporary, created on-site, within the cities or in the harbors, in the water or on the water, visible from the banks or from the river, the works take you off to explore a fascinating estuary, its heritage and its landscapes between fragile nature reserves and huge industrial buildings.

“All in all, 30 sites are transformed by artists and you may explore them by foot, bike, car (car parks nearby) or by boat, in the heritage and art places or planning your own itinerary!”

(The quote includes some minor modifications by me for translation clarity.)

Some of the exhibits are deliberately nonliteral, even optical illusions, designed to engage the viewer’s imagination. The thirty installations include a “floating house,” a “chimney house” that mimics a nearby industrial facility, a playful garden, and a former submarine dock transformed into a living exhibit of the estuary’s vegetative diversity. Some are visible only at night or from singular perspectives. (This catalog was a sort of funky download for me, but it will give you an idea of the creative range. It is from 2007, when the project was first installed.) I have long been a fan of using art in creative ways to catalyze revitalization and celebrate sustainability. I think all of the Americans in our delegation who were exposed to Estuaire will remember it well and fondly, linking the pieces to the broader concepts of the estuary and the river.

Learning

There is a little bit to be learned from all of these projects, I think. Their green ambitions are significant if not always explicit, and they are nothing if not bold. While the pragmatist in me tends to favor incremental approaches, there is a lot to be said for bold strokes that compel our attention. The latter can inform and inspire the former.

There may be something these projects and approaches can learn from us, as well: we visited ten projects in three cities over four days and, while the French projects struck me as more environmentally ambitious than most American ones, and certainly more grand in their scale, what our best projects may get better than theirs is an emphasis on walkability and harmonious connectivity at the human scale of the streetscape. But, most of all, there may be something to be learned from the very concept of having a European Green Capital. Sadly, much of America remains suspicious of government, suspicious of cities, and suspicious of bold green initiatives. Someone in our group mentioned in our closing session how striking it was that there seemed to be so much more of a social and political consensus around these issues in France. “Consensus” is not a word that applies much to current American public affairs.

Now here’s the elephant, out and about:

Related posts:

- How Hamburg became the European Green Capital (November 21, 2011)

- Pursuing nonsprawling city growth with major brownfield redevelopment: the Sacramento Railyards (October 19, 2012)

- Can US communities learn from this European suburban retrofit? (February 22, 2012)

- New data confirm European transportation habits are much greener than those in US cities (October 27, 2011)

- What makes the Jardin du Luxembourg work so well? (September 16, 2009)

Move your cursor over the images for credit information.