Whither intelligent vehicles and automated highways? (with Lee Epstein)

Posted June 17, 2013 at 2:00PM

(Today's article is co-authored with my friend and frequent collaborator, Lee Epstein. Lee is an attorney and land use planner working for sustainability in the mid-Atlantic region.)

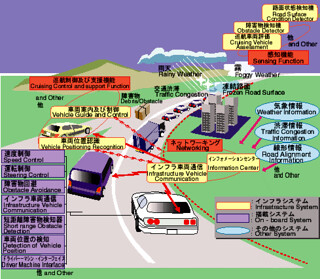

The promise of a fully automated highway network has captivated the imaginations of futurists and aspirational engineers for several generations. In these visions there is a wide range of so-called “intelligent vehicle systems” or “automated vehicles” – from private vehicles that continuously “talk” to one another while keeping some level of human control, to fully automated networks that entirely take over one’s vehicle, using embedded GPS and other technologies to get one to a desired location without a human driver touching the wheel or the pedal. The optimistic goal seems to be to achieve just the right travel distance to maintain high speeds, more efficiently manage travel volumes, and avoid accidents.

Indeed, as far back as the 1939 New York World’s Fair, General Motors’ Futurama exhibit presented designer Norman Bel Geddes’s “magic motorways” – a network of modern expressways whizzing private automobiles on automated highways through urban areas and vast suburbs. What a wonder, observers thought.

We built part of it, the expressways at least, beginning in the 1950s. In some places, we’re still building them today. And, in part, it was a wonder, facilitating new commerce and faster connections between and sometimes within cities, and to and from the new suburbs that the modern highways enabled. It was a heady era for a while. But, over time, a more troubling set of consequences emerged.

The new roads surely brought commerce to urban regions, but they also allowed those regions to spread out thinly, displacing hundreds of thousands of square miles of working farms, ranches, woodlands, wetlands,  natural stream valleys, open range, and unique desert environments. Meanwhile, inside cities, roads, expressways and entrance/exit ramps destroyed entire neighborhoods and split cities apart. Tailpipe pollution introduced the word “smog” to our vocabulary and insidious health risks to our children and elders. And eventually we learned that expressways don’t even facilitate travel that well within cities and suburbs (they do, for the most part, facilitate intercity travel), since they inevitably fill with cars and trucks to the point of paralyzing congestion.

natural stream valleys, open range, and unique desert environments. Meanwhile, inside cities, roads, expressways and entrance/exit ramps destroyed entire neighborhoods and split cities apart. Tailpipe pollution introduced the word “smog” to our vocabulary and insidious health risks to our children and elders. And eventually we learned that expressways don’t even facilitate travel that well within cities and suburbs (they do, for the most part, facilitate intercity travel), since they inevitably fill with cars and trucks to the point of paralyzing congestion.

Given this history, is there any reason to believe that automating the whole experience will make life (and our environment) better? We have our doubts.

In an article on The Atlantic Cities website this spring, urban observer Emily Badger reported on “driverless cars,” taking off from an earlier article by Tom Vanderbilt in Wired. Her story included an animation by University of Texas computer scientist Peter Stone, showing how an intersection might flow much more efficiently if fully automated and optimized for vehicle flow. In a way, the visualization is the natural successor to the gee-wizardry of Bel Geddes’s 1939 General Motors’ exhibit. Badger wrote and ended her piece with some healthy skepticism, however: “[W]hether we want to turn the personal car into a private train-like experience is a whole other question. But it’s probably not one for a computer scientist.”

Tim Maly, of the design/tech website Co.Design, recently had another take, in “Watch What Traffic Will Look Like When Cars Drive Themselves” (he also used Stone's animation in his piece). Noting that there was already unseen but substantial automation in our traffic systems, Maly quoted from an essay, “Blocking All Lanes,” by Sean Dockray, Fiona Whitton, and Steven Rowell in The Infrastructural City in which the authors traced the slow transformation from the standing policeman regulating traffic at a busy intersection to the modern sensor- or camera-activated signals employed today. He then used the same vision of change to trace a future transformation from a human vehicle driver with her hands on the wheel and foot on the gas or brake, to a high-tech system of mechanical precision steering and acceleration/braking networked with “GPS, proximity sensors, local mesh networks, or video cameras.” Maly made no value judgment, but did say that, in some places like China or Japan, such systems might make eminent sense.

In our view, these articles are provocative but don’t go far enough to ask and address important questions – in part for some of the reasons noted above. Fully automating highways may make traffic move more quickly and safely (if everything works as planned, right?) for a while, but what will they mean over time for the human and natural environment? Won’t the new types of roads eventually fill up just as the old ones have? Would such beautifully flowing, electronically choreographed, completely automated cars and intersections be compatible with fully and adequately accommodating pedestrians and bicyclists in a well designed, walkable urban environment? If so, how, exactly?

And would the development and use of such “intelligent” systems be any less, or indeed more, likely to lead to the unending extension of highways into exurban areas, or through rural areas – possibly promoting continuation of an unsustainable, sprawling growth spiral?

Our societal values around driving, walkability and the shape of cities are changing. Indeed, we have learned that in many instances, particularly for freeways within cities, building them has brought more negative consequences than positive ones. Enlightened cities are beginning to take old freeways down and replacing them with people-friendly boulevards. Could this be a step not forward but back, to an era when the emphasis was all about moving as many cars as possible as quickly as possible, rather than on creating better environments for humans that don’t rely so much on cars? What set of ethics should accompany this bold new technology?

These are not necessarily questions wholly without answers, but these very real concerns should be part of the study and analysis of self-driving vehicle technology. They should certainly be part of the discourse in the popular media. The last sixty years or so of freeway-building and its consequences don’t exactly inspire confidence that the right answer is to focus on freeways divorced from context.

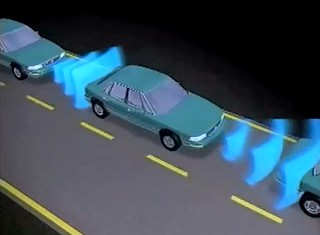

It’s also hard to place much trust in regulatory and government agencies, which sometimes have too limited a mission or outlook to take this broader perspective into account. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), for example, recently set out 14 pages of guidance concerning automated highway/vehicle systems. NHTSA is focused on the safety potential of such technologies – for example, if they prevent crashes that occur from vehicles following too closely. Surely that is critically important, but it doesn’t begin to address the broader contextual issues.

It’s also hard to place much trust in regulatory and government agencies, which sometimes have too limited a mission or outlook to take this broader perspective into account. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), for example, recently set out 14 pages of guidance concerning automated highway/vehicle systems. NHTSA is focused on the safety potential of such technologies – for example, if they prevent crashes that occur from vehicles following too closely. Surely that is critically important, but it doesn’t begin to address the broader contextual issues.

While it may be conceivable for bright engineers, planners and designers to come up with ways to fit such systems carefully and properly into people-first, walkable urban environments, at a minimum that fitting needs to be done as the systems are conceived and tested rather than as an errant afterthought. Likewise for the possibility that these systems will exacerbate sprawl: there are policy approaches that can moderate the spread and extension of highways, and/or to keep sprawling growth to a minimum – but, again, the track record is not inspiring. These policies need to be considered, developed and adequately applied concurrently with the application of the new technologies, before the damage is inevitable.

Don’t get us wrong. We’re as enamored of new whiz-bang technology as the next guy or girl. But just because the word “intelligent” is used in a title doesn’t make it accurate – especially when it comes to sustainable urban regions in an era still suffering from past development and infrastructure mistakes.

In short, just because it’s high tech doesn’t make it better. Indeed, there are lots of “old fashioned” things we need to get right about our cities, urban regions, and transportation systems before we play with expensive new technology that still doesn’t solve those basic problems: we would place a higher priority on ensuring that cities are safe, hospitable to all, walkable, a pleasure to be in, and green (both naturally, and existentially); on urban/suburban regions that have defined limits, conserving important resource lands around them; and on transportation systems that help us get efficiently from point A to point B, but which take fully into account the first two problems as effectively as they solve the last.

Related posts:

- Federal court says highway sponsors must first study transit, impacts on suburban sprawl (June 5, 2013)

- Traffic explained, then fixed in 4 entertaining minutes (April 17, 2012)

- Running freeways through cities has often been a costly mistake. So, what now? (March 5, 2012)

- Freeways without futures (March 31, 2011)

- Is there a downside to "intelligent cities" or "smart cities"? (March 3, 2011)

Move your cursor over the images for credit information.