We need more driving-optional neighborhoods (excerpted from People Habitat)

Posted November 18, 2013 at 2:24PM

(Today’s post is excerpted from my forthcoming book, People Habitat: 25 Ways to Think About Greener, Healthier Cities.)

Counter to the enviro stereotype, I like cars and I like driving. Those who know me well know I’m telling the truth and, if you’re looking for a purist manifesto, you’ve found the wrong guy. In fact, maybe it’s my 1960s North Carolina upbringing, but I like nice cars and have always managed to have one, thank you very much.

What I would not like, though, is being dependent on a car for every single thing I need or want to do. I also like public transit when it’s working well – I’ve literally met some of my best friends while on public transportation – and I frequently use it for commuting. I love walking places, especially city places, and generally manage my daily chores other than commuting on foot. And I’m passionate about bicycling, too, though I ride for fitness, not everyday transportation. I guess you could say that I’m a multi-modal kind of guy, and I feel lucky that my living conditions allow me to practice a life of transportation-by-choice.

I know most Americans aren’t so fortunate. Ours is an overwhelmingly auto-oriented landscape, except in a few big city downtowns and older neighborhoods, many populated mostly by residents without kids. Most people have to drive to get to work or school, to go out to eat, to take their laundry and dry cleaning for service, to shop for groceries. If they have children, chances are they are also spending a lot of time shuttling the kids around from one event to another. It’s normal, I think, by today’s standards. But it’s not much fun.

I’m old enough to remember when driving was fun. If you can tell a lot about a society’s culture from its popular music lyrics, the 1960s were surely the golden age of the American automobile. On July 4, 1964, a new single became the first number one song by that most American of bands, the Beach Boys. Performed with a driving beat and Brian Wilson’s soaring harmonies, “I Get Around” celebrated the unequivocal freedom and exuberance that cars provided, particularly on the group’s home turf of southern California:

We always take my car ‘cause it’s never been beat

And we’ve never missed yet with the girls we meet . . .I get around

Get around, round, round, I get around

From town to town . . .

Readers of a certain age may also recall that other hit songs of the 1960s included such paeans to the automobile as “GTO” (Ronny and the Daytonas), “Mustang Sally” (Wilson Pickett), and several more by the Beach Boys, including “Little Deuce Coupe” and “Fun, Fun, Fun.” Prince kept up a smidgen of momentum with “Little Red Corvette” as late as 1983.

By the turn of the twenty-first century, though, exuberant car songs were confined to oldies radio stations. If cars show up in lyrics today, chances are that the song is something darker and considerably less innocent than those popular fifty years ago. One can speculate on the reasons, but surely one of the most compelling is that it has been quite a while since driving was “fun, fun, fun” for most Americans.

Instead, for most driving has become simply a matter of getting from point A to point B, and far too often doing so hampered by traffic congestion and stress, to say nothing of the havoc wreaked on our natural environment. Instead of the open convertibles that symbolized the most desirable cars of the 1960s, sport utility vehicles – essentially complete family rooms (if not fortresses) on wheels that isolate their passengers as much as possible from the external world – became the preferred vehicles of the 1990s and early 2000s.

What happened between the golden age of the automobile and today? Just as cars made it possible to expand our communities far beyond traditional downtowns and rail corridors, the act of spreading out – suburban sprawl – placed increasing distances between the various places where Americans live, work, shop, go to school, and worship. The increased distances inevitably led to a tremendous increase in driving: the number of miles driven annually by passenger cars in the US has tripled since the 1960s, reaching a peak of just over three trillion in 2007. While the dramatic growth in driving has begun to reverse in recent years (in part because of the financial crisis and recession that hit the country beginning in 2008, though also in part because of changing generational preferences), we still have a long way to go before approaching anything near sustainability.

With two-thirds of oil use in the US going to transportation, the average American now uses over twice as much oil as the average person in other industrialized nations, and over five times as much as the average person in the world as a whole. As a result, carbon dioxide emissions from driving in the US remain some 35 percent higher today than they were even as recently as 1990. The US continues to lead the western world in per capita carbon emissions, emitting about twice as much of the potent greenhouse gas per person as Germany, the United Kingdom, or Japan, and about three times as much as France.

Given these sobering facts, the challenge in creating sustainable people habitat is to maximize convenience and livability for the community’s residents, workers and visitors while minimizing the burdens on the environment created by the basic need simply to, as the Beach Boys put it, get around. The task is an especially important one, given the relative importance of transportation to energy consumption and corresponding greenhouse gas emissions. A 2007 study reported in Environmental Building News demonstrated that the amount of energy used (and greenhouse gases emitted) by a typical office building’s operation is dwarfed by the amount that employees and visitors typically consume getting there and back.

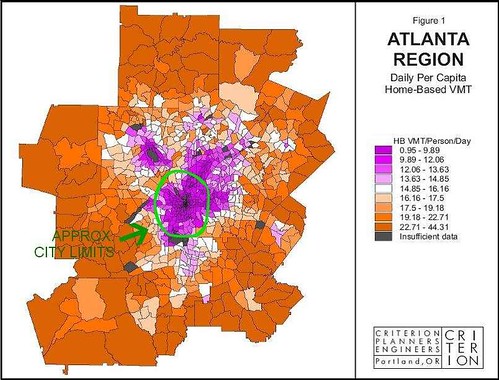

To me, the most interesting aspect of Americans’ overwhelming dependence on driving is that people’s driving habits are not distributed evenly. With the wonderful world of GIS (geographic information systems) mapping, you can see a geographic representation of miles driven per household: those of us in outer suburbs drive a lot more than those of us in more urban locations, whether the latter are in city centers or in the hearts of older towns and suburbs.

In 2010, transportation uber-researchers Reid Ewing (University of Utah) and Robert Cervero (UC-Berkeley) published a painstaking ‘meta-analysis’ of nearly 50 published studies on the subject of land use and travel behavior. Writing in the Journal of the American Planning Association, the two returned to a subject to which they have dedicated most of their careers, in this case updating their previous meta-analysis from 2001.

What they found: When it comes to land use, driving and the environment, location matters most. The study's key conclusion is that how close a household is to common trip destinations is by far the most important land use factor in determining a household or person’s amount of driving. Such “destination accessibility” almost always favors central locations within a region; the closer a house, neighborhood or office is to downtown, the shorter the average distance one has to travel to other places and the lower one’s rate of driving. The authors found that central locations can be almost as significant in reducing driving rates as other significant factors (e.g., neighborhood density, mixed land use, street design) combined.

The clear implication is that, to enable lifestyles with reduced driving, oil consumption and associated emissions, environmentalists should continue to stress opportunities for revitalization and redevelopment in centrally located neighborhoods. As Ewing and Cervero put it: “Almost any development in a central location is likely to generate less automobile travel than the best-designed, compact, mixed-use development in a remote location.” This also means that the current near-exclusive emphasis in the US environmental community on mode shifts (from driving to transit, or to walking or bicycling) misses the biggest opportunity of all to reduce vehicle miles traveled: shortening driving distances through better land use.

So, what about people such as myself, who enjoy driving sometimes when it’s a matter of choice? Can we as a society get back to the optimistic, exuberant feelings of driving in the early 1960s? Maybe not: we have done some damage to the planet since then, and these are more sobering times for other reasons, too. If we can reclaim exuberance, it is unlikely to be because of cars and driving. But we can start down the road, so to speak, and being more thoughtful about our built environment can help.

So, what about people such as myself, who enjoy driving sometimes when it’s a matter of choice? Can we as a society get back to the optimistic, exuberant feelings of driving in the early 1960s? Maybe not: we have done some damage to the planet since then, and these are more sobering times for other reasons, too. If we can reclaim exuberance, it is unlikely to be because of cars and driving. But we can start down the road, so to speak, and being more thoughtful about our built environment can help.

Our goal should be to create more driving-optional neighborhoods. Achieving it will be harder to accomplish in suburbs and smaller towns than in cities, but even in less accessible locations we can still plan and design our communities more thoughtfully to encourage walking and shorter driving distances, and make a difference. Given the massive increases in population expected for the US and elsewhere over the next half-century, we had better get to it . . .

(People Habitat: 25 Ways to Think About Greener, Healthier Neighborhoods will be available from Island Press and all major booksellers in January 2014.)

Related posts:

- How LEED-ND standards reduce driving and associated emissions: new research (June 12, 2013)

- There must be a there (excerpted from People Habitat) (May 8, 2013)

- Cities and the ecology of "people habitat" (March 27, 2013)

Move your cursor over the images for credit information.