Can people live in harmony with nature on the Galapagos?

Posted November 15, 2012 at 1:00PM

Sometimes work that on its surface is modestly scaled can be of immense significance, because it addresses a very special place or issue or has the potential to create a model for others to follow. Both of these apply to the very good work of the Prince's Foundation for Building Community and their local partners in the Galapagos Islands. (I have written previously about the Foundation's excellent work in another island nation, Jamaica.)

The Galapagos, part of the state of Ecuador, comprise one of the world’s richest ecosystems. The islands are home to myriad endemic species including, just for example, land and marine iguanas, giant tortoises, sea cucumbers, seafowl (including the famous blue-footed booby), penguins, sea lions, and the only living tropical species of albatross. Indeed, Charles Darwin’s observation of bird species on the Galapagos led, in significant part, to the development of his theory of natural selection and his seminal work The Origin of Species.

In 1986, 27,000 square miles of ocean surrounding the Galapagos was declared a marine reserve, second in size only to Australia's Great Barrier Reef. UNESCO recognized the islands in 1978 as a World Heritage Site and, in 1985, as a biosphere reserve.

But, can this very special place stay this way? The permanent human population remains small but growing, having risen rapidly from around 2,000 in 1959 to over 30,000 today, and the islands have become an increasingly popular tourist destination. Giving cause for immediate concern, a housing project known as El Mirador is bringing 1,130 new homes to the town of Puerto Ayora, expanding the town's current footprint by 40 percent. All of the lots have been sold and construction of houses has begun.

The good news is that 97 percent of the Galapagos is a protected national park, relegating human activity, including agriculture, to the remaining three percent. But humans’ ecological footprint is larger, especially given the islands’ popularity with tourists. There is an acute need to balance the islands’ unique and fragile environment with its human population growth and need for economic stability.

Fortunately, local leaders realize this. There is now some significant but realistic planning going on, with acute sensitivity to the islands’ special culture and needs. At NRDC, we were visited last week by Pedro Quintanilla and Samantha Singer of the London-based Prince’s Foundation. The two planners have been living on the islands for a year, having been invited by the Galapagos Regional Government (Consejo de Gobienero de Galapagos). “Urban” planning in the Galapagos may seem counter-intuitive, the two explain on their blog site, but isn't:

"When we mention that we are going to be working on urban planning in the Galapagos, there are generally two reactions: either we learn new facts, figures and species, or a moment of pause and then expression of surprise to find that people live there at all. The reality is that in the Galapagos Archipelago is a current human population of approximately 30,000 people, the economy is fueled by over 100,000 tourists a year, and growing . . .

“Major issues and challenges that face the islands are those of unprecedented and poorly controlled urban development. The pressure of tourism and human presence on the islands is constantly increasing and threatening the reason people want to see this amazing place, the incredible natural environment. The quality and coordination of development is a huge challenge but could be an example to the world of how humans could live in harmony with nature.”

The Prince’s Foundation is working with, in addition to the regional government, the Galapagos Conservation Trust, the Charles Darwin Foundation, the World Wildlife Fund, and local municipal governments.

WWF, in particular, has been addressing waste issues on Isla Isabela, the largest Galapagos Island in terms of land mass; remarkably, Isabela is still being created, because of the presence of active volcanoes; Volcan Negro, for example, last erupted in 2005. The island’s one settlement, Puerto Villamil, has 2000 residents, with no sewage or water treatment system.

As a result, sewage is either leaking into residents’ tap water or into the bay, and many townspeople have already suffered serious infections, according to the Prince’s Foundation's website. Puerto Villamil has recently expanded onto lava fields that are effectively desert, hospitable only to cacti. The Foundation’s planners hope to assist the town with codes and master plans to guide more healthy development.

More broadly, the Foundation’s team has engaged substantially with Galapagos residents while also recruiting the assistance of outside experts on planning and development issues throughout the islands. It has already delivered some impressive work products, especially with respect to El Mirador, which is likely to have the largest impact of any currently anticipated change in the islands.

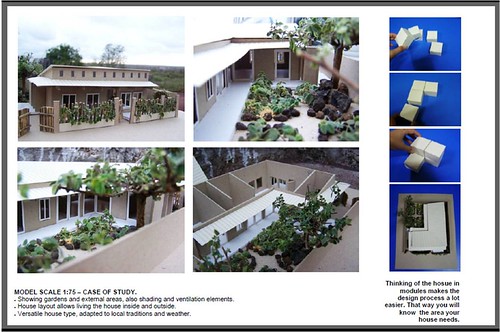

One impressive work product is Scalesia: A unified System of Development for El Mirador. The document contains architectural best practices suited to local conditions, cost-effectively taking advantage of climatic conditions such as shade and wind direction while suggesting sustainable practices for vegetation (including gardening) and for water collection and management. Since many residents will be engaged in the building of their own homes, the guide is keyed to them.

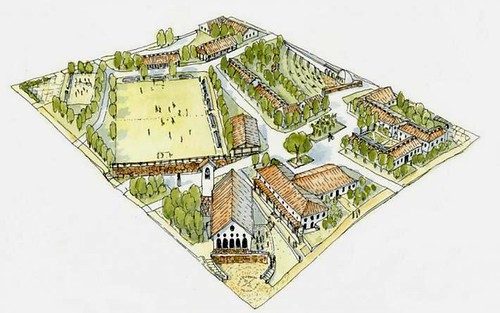

More detailed is the Report of the Code Workshop for El Mirador, a 40-page bilingual document addressing landscape, street layout and design, architecture, and infrastructure. It includes a conceptual design for the new community’s center, with a town hall, church, market, open theater, pharmacy, child care facility, and sports fields. The report recommends a modular approach to home design that allows residents to build in phases as needs and finances dictate. It includes basic plans for homes that can be built for a number of cost estimates ranging from $19,000 to $66,200.

The report also suggests an integrated community approach to water and sewage management and to energy, with a rainwater collection and filtering system for drinking water, and a “biodigester” for converting solid waste into methane that can be used to generate electricity. While the new code was created specifically for El Mirador, the report notes that it could be applied to the whole of Santa Cruz island. You may read it in detail here.

Beyond measures that would need to be adopted by the municipality, the team worked with El Mirador resident Enrique Ramos to write a sort of “citizens’ code” for the new development that could gently guide its residents to a more sustainable lifestyle. It’s hard to argue with its principles and its earnestness:

THE DWELLERS

- In this neighborhood live people from all over the country, all races and cultures, and we are aware we are in a unique natural site, which we want to protect for our children's children.

- We know our neighbors and we respect them.

- We are tolerant of diversity: we have no discrimination based on sex, gender, race, religion, ability, personal or social situation.

- Our participation is always important for the care and improvement of our development. It is our right and our obligation to participate and do so responsibly.

- We work together to build a better place to live.

RECREATION SITES

- There are places for healthy recreation and leisure where the language we use is respectful.

- Care and education is essential to properly use public facilities.

WATER

- Water is scarce; we must use it rationally. In our homes we must collect rainwater and store it carefully to avoid contamination.

WASTE

- The waste produced in the home must be separated and classified according to the standards of recycling.

- We avoid using disposable bags and containers, to reduce unnecessary consumption.

- Know and apply the list of [species] permitted, restricted, and not allowed to enter the Galapagos.

- We are cautious about using animal or plant species that can become pests and alter our environment.

- We do not want to alter the natural life, so do not feed or touch the native and endemic animals.

- We are responsible for our pets and their care in our home and in public places.

- We do not allow poultry on the premises.

MOBILIZATION

- Walking or cycling are preferred over driving.

- Drivers need to comply with the standards of speed and courtesy for pedestrians and cyclists.

HEALTH

- No smoking in public places. Avoid smoking in areas with dry vegetation.

- Listening to music on moderate volume is recommended so as not to disturb the neighbors.

- To maintain a healthy body we must exercise.

Idealistic? Sure. And, by the standards of progressive American environmentalists, perhaps also a bit modest. But the idea is not to expect - or legislate - dramatic commitments overnight, but to work with Galapagos citizens to instill a commitment to sustainability that will last because local residents will come to own it.

Essentially, the Foundation and its local partners are working to create the beginnings of a planning culture where none has existed before, and a sustainability culture that is articulated rather than just assumed. Given the fragility of the ecosystem, the growth trend, and the dependence of the island economy on tourism, it seems incredibly pertinent. We can be glad, and so can the critters.

Related posts:

- Can we balance the old and new as a place evolves? (December 28, 2011)

- The greening of DC's LeDroit Park neighborhood (featuring a Baptist church, a farm, & HRH The Prince of Wales) (May 5, 2011)

- Cincinnati students plan redevelopment area of Brazilian city for the next World Cup (July 29, 2010)

- HRH the Prince of Wales on building a better community – in Wales (April 13, 2010)

- Revitalization in the third world: Rose Town, Jamaica explores healing through restoration (October 7, 2009)

- The World’s Best Job (hint: it involves placemaking, but not in the US) (November 19, 2008)

Move your cursor over the images for credit information.

Please also visit NRDC’s sustainable communities video channels.