They are stardust. They are golden. But are they right about “shrinking cities”?

Posted July 2, 2009 at 1:32PM

Warning: this is a long one.

Readers of a certain age will remember Joni's Mitchell's iconic anthem "Woodstock," celebrating the famous 1969 music festival (which, incidentally, she did not attend, but I digress). The song became a monster hit for Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young (who did attend) in 1970. Its chorus, propelled by the group's trademark high harmonies, called us to get "back to the garden":

We are stardust

We are golden

And we've got to get ourselves back to the gar-ar-arrrr-ar-arr-ar-dennn . . .

It was, and is, a fantastic song. But it is not, I repeat not, a reliable environmental solution to urban problems. Unfortunately, it does fairly characterize where a lot of the environmental movement's sentiment and energy was in the 1970s when we, pretty much like everyone else, vilified cities and romanticized the countryside. I remember that, when NRDC founded its urban program in the mid-1980s, it was actually an unusual thing for an environmental group to do.

What we didn't realize then, but now do (a lot of us, anyway), is that auto-dependent sprawl with solar panels and compost is still, well, auto-dependent sprawl. And that compact, walkable cities, suburbs, and towns are not the problem but the solution.

The push to reclaim large parts of "shrinking cities" for nature

Which brings me to something that is becoming all the rage with a certain stardust-tinged segment of the planning world: re-vegetating older, industrial "shrinking cities" with green space where vacant properties and isolated occupied homes now stand. Let's clear the debris of vacant houses and lots, the argument goes, and turn their spaces into gardens and natural areas, since the economies of Detroit, Buffalo, Baltimore and the like can't support repopulation. In other words, just as some of us had finally convinced the environmental movement of the terrific value of cities in reducing per-capita environmental impacts, along comes a movement to de-urbanize cities.

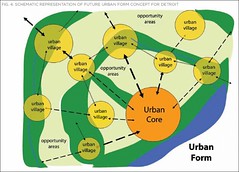

I noted my concern with this strategy last month in a post about Detroit, which has been presented with a plan by an architects' study group to do exactly that. (See image: everything outside the designated "centers" would be proposed for greenways or reserved as "opportunity areas" for potential agriculture.)

I noted my concern with this strategy last month in a post about Detroit, which has been presented with a plan by an architects' study group to do exactly that. (See image: everything outside the designated "centers" would be proposed for greenways or reserved as "opportunity areas" for potential agriculture.)

My post led to a thoughtful rebuttal from Jason King (who had been part of the study group) on his own blog, Landscape+Urbanism. (Blog vs. blog - am I 21st century or what?) I should add that I am a regular reader of King's commentary and always find it provocative and beautifully illustrated if sometimes not quite as urbanist as I might like. His point here is that it is only realistic to consider "shrinking cities" for what they are, and find an approach that responds to their new paradigm. King, who is a landscape architect, seems quite enamored of the "shrinking cities" idea, having blogged about it four times in the last three weeks.

At least King says he isn't the source of the report in the Detroit Free Press (quoted here) that "the committee suggests that Detroit could recreate itself as a 21st-Century version of the English countryside." (Apparently that comes from another thoughtful and nice guy on the team, Alan Mallach, with whom I have had the pleasure of serving on a now-defunct AIA committee. But really.)

It's gaining traction but, fortunately, some neighborhoods will escape

The idea is definitely catching on, reportedly even in the Obama administration. An article by Tom Leonard in the London-based Telegraph, headlined "US cities may have to be bulldozed in order to survive," puts it this way:

"Dozens of US cities may have entire neighbourhoods bulldozed as part of drastic 'shrink to survive' proposals being considered by the Obama administration to tackle economic decline.

"The government is looking at expanding a pioneering scheme in Flint (MI), one of the poorest US cities, which involves razing entire districts and returning the land to nature . . .

"The radical experiment is the brainchild of Dan Kildee, treasurer of Genesee County, which includes Flint.

"Having outlined his strategy to Barack Obama during the election campaign, Mr Kildee has now been approached by the US government and a group of charities who want him to apply what he has learnt to the rest of the country.

"Mr Kildee said he will concentrate on 50 cities, identified in a recent study by the Brookings Institution, an influential Washington think-tank, as potentially needing to shrink substantially to cope with their declining fortunes . . ."

I should note here that Jennifer Leonard of the National Vacant Properties Campaign, who has been working with Dan Kildee, says that he was mispresented by this article and actually wants to do something more limited than the article suggests.  I hope so, and I'll get to that toward the end of this post. Looking at ways to "shrink" neighborhoods in fifty cities? Yikes.

I hope so, and I'll get to that toward the end of this post. Looking at ways to "shrink" neighborhoods in fifty cities? Yikes.

Look, maybe there's a happy medium somewhere. Appropriately-sized neighborhood green space can be great for cities and their residents. But I for one am really, really glad this idea didn't have traction a decade or two ago, when it easily could have led to the demolition of vacant houses and properties in such wonderful, now-recovering neighborhoods as Old North Saint Louis (photo of new farmer's market above), Boston's Dudley Street, or even Cincinnati's Over-the-Rhine, now poised to become a national model of revitalization done well. Every one of those terrific neighborhoods could have been subjected to the same logic, since they all suffered serious decline and depopulation in weak-market regions before things began to turn around in recent years.

We won't solve the problem without addressing the cause

I also wish the turning-cities-back-to-nature crowd would give at least some mention to a major reason why these places now have vacant properties: the flight of investment and population to the metro fringe.  Everyone is saying or implying that it is all the decline of the industrial economy, but it's not that simple. Most of these regions are not, in fact, declining in population much or at all: The metro areas of Detroit, Baltimore and Boston all grew from 1990 to 2003. Metro Baltimore and Boston continued to grow in the 2000s; metro Detroit did decline between 2000 and 2008, but only by six-tenths of one percent. Areas like Rochester and Syracuse, frequently put in the "shrinking city" column, also basically have been holding steady in the 2000s. There are indeed regions that are shrinking, some in the Rust Belt, but almost none by more than five percent (Pine Bluff, Arkansas is one of the exceptions).

Everyone is saying or implying that it is all the decline of the industrial economy, but it's not that simple. Most of these regions are not, in fact, declining in population much or at all: The metro areas of Detroit, Baltimore and Boston all grew from 1990 to 2003. Metro Baltimore and Boston continued to grow in the 2000s; metro Detroit did decline between 2000 and 2008, but only by six-tenths of one percent. Areas like Rochester and Syracuse, frequently put in the "shrinking city" column, also basically have been holding steady in the 2000s. There are indeed regions that are shrinking, some in the Rust Belt, but almost none by more than five percent (Pine Bluff, Arkansas is one of the exceptions).

So, yes, some central cities have depopulated badly (though even within the central city limits the rate of loss generally appears to be slowing), but most of their regions have continued to sprawl. I haven't reviewed the most recent statistics but, in the 1980s and 1990s, Pittsburgh grew in developed land six times faster than in population; Boston five times faster; Chicago and Cleveland four times faster; Baltimore 2.5 times faster; and so on. Greater Buffalo grew by 50 percent in developed land between 1982 and 1996, even while experiencing no growth at all in population; the metro regions of Detroit and Rochester grew in developed land by 20 percent and 16 percent, respectively, even while shrinking slightly in population during that period.

Viewed from this perspective, the problem is not one of much if any real metro area depopulation but mainly the changed geographic distribution of that population as regions have failed to address sprawl.  That is a problem that needs fixing. Converting large amounts of currently urban land "back to the garden" without also addressing sprawl will only ensure that any further population shifts or recovery will occur in favor of the fringe, where the per-capita environmental damage is the greatest.

That is a problem that needs fixing. Converting large amounts of currently urban land "back to the garden" without also addressing sprawl will only ensure that any further population shifts or recovery will occur in favor of the fringe, where the per-capita environmental damage is the greatest.

Regional problems need regional solutions

Put another way, if you're a doctor with a patient suffering from trauma and blood loss, first you stop the bleeding. Then you proceed to surgery, if necessary. But so far no one is suggesting anything of the sort. So many well-minded people remain trapped in the artificial jurisdictional straitjacket that looks only within the central municipality's borders, ignoring the reality that the larger region is where the deeper solutions lie.

The president himself has acknowledged that 21st-century challenges are more regional than municipal, in a 2008 campaign address on "the new metropolitan reality":

"It's not just our cities that are hotbeds of innovation anymore, it's those growing metro areas. It's not just Durham or Raleigh - it's the entire Research Triangle. It's not just Palo Alto, it's cities up and down Silicon Valley . . .

"To seize the possibility of this moment, we need to promote strong cities as the backbone of regional growth. And yet, Washington remains trapped in an earlier era, wedded to an outdated 'urban' agenda that focuses exclusively on the problems in our cities, and ignores our growing metro areas; an agenda that confuses anti-poverty policy with a metropolitan strategy, and ends up hurting both . . .

"Yes, we need to strengthen our cities. But we also need to stop seeing our cities as the problem and start seeing them as the solution. Because strong cities are the building blocks of strong regions, and strong regions are essential for a strong America. That is the new metropolitan reality and we need a new strategy that reflects it . . ."

Moreover, some of these "shrinking" central cities are just now beginning to show a few signs of potential. While central cities in weak-market areas are still claiming an unfortunately small share of overall metro growth, it is worth noting that their share of that growth has been increasing from the 1990s to the 2000s. Cities where this has occurred include Baltimore, Milwaukee, Providence, Rochester, Saint Louis, Cleveland, Cincinnati, and even Detroit, among others. This is not the time to surrender their potential to the suburbs.

A happy medium?

Now, I'm OK with converting smaller tracts of vacant and derelict land into urban green space, which could turn out to be a net plus for all concerned, and maybe that's where the happy medium comes in. Appropriately scaled parks for walkable neighborhoods are great for a lot of reasons, not least because they can support future investment and development.

And I'm definitely OK with targeting public urban investment to nodes within a city that have the most potential to recover, as suggested some time back by Joe Schilling of Virginia Tech and the National Vacant Properties Campaign. It makes some sense to engage those neighborhoods first and then, if there are results, move to additional areas.  The article in which Joe's thoughts are cited points to a very successful program in Richmond (example, photo left) that has demonstrated the viability of targeting.

The article in which Joe's thoughts are cited points to a very successful program in Richmond (example, photo left) that has demonstrated the viability of targeting.

But going ambitiously after 50 inner cities to address supposed depopulation issues with land conversion while most of them are in regions that are relatively stable or growing? And doing nothing about the sprawl that is a major source of the problem? Good heavens.

I'm not alone

Having done a little research, I am relieved to learn at least that I am not the only one who thinks we should proceed very cautiously with re-purposing these neighborhoods and direct our attention to the entire region, not just the central city. Richard Layman is another writer that I read regularly, in his blog Rebuilding Place in the Urban Space:

"Because I think that the dynamics of urban decline and the possibilities for revitalization are more nuanced . . . the 'solution' offered by Dan Kildee, treasurer of Genesee County north of Detroit, as recounted in the story, 'US cities may have to be bulldozed in order to survive,' [linked above] is too harsh and can't be applied categorically . . .

"Cities that have relied on manufacturing will have to shrink somehow. But the real issue is continued outmigration and expansion and greater utilization of land per capita in metropolitan areas. In short, metropolitan regions continue to expand significantly, at rates greater than that generated by population growth."

Mathieu Helie, writing on the blog Emergent Urbanism, is another skeptic who believes the proposed solutions need to be better considered:

"If we embrace complexity, then the randomly sized pockets of open land are an exceptional opportunity to renew the city of Detroit. They form a fractal solution set to new construction that many different people can participate in and contribute to. It can accommodate small, medium-size and eventually large-size businesses in close proximity with diverse housing and convenient transportation structures . . ."

Writing in the Los Angeles Times, Gregory Rodriguez's views come close to my own:

"The plan makes sense on some level, but it's disturbing on another. Anyone who's driven by miles of empty lots in Detroit knows that urban demolition does more than destroy blight. It also erases history and what a city was.

Traces of the past have always been jumping-off places for the next chapter (think rehabbed Victorians or sleek post-industrial lofts). And, of course, the back-to-nature plan -- which could be used in cities such as Memphis, Baltimore, Philadelphia and others -- is fundamentally an admission and may be an assurance that these cities will never rise again."

More hopeful models

There are other, more hopeful models. Roberta Brandes Gratz, author of Cities Back from the Edge and The Living City, points on Citiwire to Wilkinsburg, a one-time streetcar suburb of Pittsburgh that has suffered major abandonment of both residential and commercial properties. The city is now benefiting from an innovative public-private-nonprofit partnership that is renovating vacant historic properties, resulting in the first home sales in the area in years.

In Buffalo, the West Side community, much like Boston's Dudley Street before it, is taking control of its own destiny, going directly to problem property owners or instituting legal proceedings to buy vacant properties cheaply and resell them at bargain prices to local buyers willing to repair and occupy them.  Gratz writes that community volunteers are also painting over graffiti, cleaning out rubble lots, crowding out drug dealers and prostitutes by strategically working with the police, planting trees, fixing sidewalks, mowing lawns and anything else to show their determination and caring. Houses are now selling; new people are moving in; and leaders from other Buffalo neighborhoods are seeking advice on how to develop a similar strategy.

Gratz writes that community volunteers are also painting over graffiti, cleaning out rubble lots, crowding out drug dealers and prostitutes by strategically working with the police, planting trees, fixing sidewalks, mowing lawns and anything else to show their determination and caring. Houses are now selling; new people are moving in; and leaders from other Buffalo neighborhoods are seeking advice on how to develop a similar strategy.

As the National Vacant Properties Campaign says on its website, "this is usable land already connected to urban infrastructure. For metropolitan areas looking to accommodate growth without consuming the surrounding countryside, these properties amount to a large reservoir of land for well-planned development." Most of these areas are still growing in the surrounding countryside.

Before publishing this post, I contacted Jennifer Leonard of the Campaign, who believes land banking is a very useful tool for dealing with vacant structures and tracts. Land banking allows a community to gain control of, consolidate, and hold troubled properties while planning for the community's future and potential recovery; a form of the practice was immensely helpful in assisting the recovery of Dudley Street in Boston.

Dan Kildee has gained a national reputation for his use of the technique in Flint, and Jennifer assures me that land banking, not wholesale conversion of urban parcels back to nature, is Kildee's real aim for "shrinking cities." I hope that turns out to be the case, though I have a fear that, if banked land is used for gardening and green space even "temporarily," communities will never welcome development on those parcels. As a result, we basically risk creating a fragmented countryside with suburban/rural densities (see rendering developed for inner-city Cleveland, above) in the center of a region. We will see.

Dan Kildee has gained a national reputation for his use of the technique in Flint, and Jennifer assures me that land banking, not wholesale conversion of urban parcels back to nature, is Kildee's real aim for "shrinking cities." I hope that turns out to be the case, though I have a fear that, if banked land is used for gardening and green space even "temporarily," communities will never welcome development on those parcels. As a result, we basically risk creating a fragmented countryside with suburban/rural densities (see rendering developed for inner-city Cleveland, above) in the center of a region. We will see.

Meanwhile, Roberta Brandes Gratz makes her central point most eloquently:

"One is hard pressed to find a city or even a neighborhood that was ever regenerated through demolition of vacant buildings. Didn't we learn of the hollow results from the discredited post-World War II urban renewal policies that destroyed - and for decades left bereft - vast tracks of troubled residential structures?"

Let's at least slow down

To all this, I would add only that a major recession is probably the worst possible time to draw conclusions about a neighborhood's - or a city's, or a region's - long-term potential for recovery. At least let's give it a wait before making long-term land use decisions that take developable inner-city land off the table, OK? And let's not use a sledgehammer to perform what probably should be delicate surgery.

Plant a neighborhood garden or create a neighborhood-scaled park? Absolutely. And enjoy it. But turn large tracts of city land "back to the garden" without also curbing sprawl on the edge? I'm not convinced.

You can still enjoy the song, though. This is a relatively recent, jazzy version by Joni: