Zoning reform, libertarianism, and the nature of community

Posted February 26, 2010 at 1:39PM

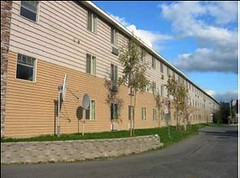

The city planners of Anchorage, Alaska, are attempting to bring that city’s land-use regulations into the 21st century. In particular, they are proposing a variation on form-based zoning that would encourage mixed uses, orientation of development to the street, and pedestrian- and people-friendly building design. This has been a massive undertaking, in the works for the better part of a decade. And it is running into opposition.

Note: Today’s post is co-authored with my good friend Lee Epstein, a seasoned and very policy-savvy environmental lawyer and land-use planner.

Longtime Anchorage planning director Tom Nelson articulated the rationale in 2006 in the Alaska Business Monthly:

“Like most cities, Anchorage's land-use regulations have encouraged single-use districts, and reliance on a single mode of transportation to connect them--the automobile. This has led to a more sprawling land-use pattern and greater consumption of energy resources than would otherwise be the case . . .

as one looks ahead, there is a need to create other viable, attractive and less energy-consumptive choices for transportation--be it walking, biking or transit--as well as to shorten distances to destinations . . .

“Mixed-use developments, winter-city design, energy-conserving buildings and transportation systems, creation of public spaces and retention of important open spaces are all increasing in usage. These trends in land development coincide with many of the solutions proposed in response to the changing economic circumstances and community aspirations in Anchorage. As developers, residents and local officials see the benefits of these attributes, Anchorage's land-use code needs to change in order to help accommodate and facilitate them.”

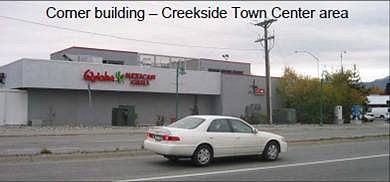

Writing last week in the Anchorage Daily News about changes the new code would bring to the commercial sector of Anchorage development, Rosemary Shinohara reports that “under the proposed new rules, a local builder no longer could put a windowless, blank side of a commercial building next to the street” but, instead, would be required to choose from a menu of options within each of three major design categories:

Windows, entrances and the building's orientation in reference to the sidewalk and street. Opening to the street rather than just to offstreet parking lots helps walkability, visual appeal, and a sense of community.

Windows, entrances and the building's orientation in reference to the sidewalk and street. Opening to the street rather than just to offstreet parking lots helps walkability, visual appeal, and a sense of community.- Building design. Shinohara: "Examples of choices are setting an upper story back from the lower stories; building a plaza; adding a second color, texture or material to the front of the building; or creating recesses or projections so the facade is not just a flat surface."

- Northern climate considerations. The code's menu includes entrances protected from the weather, sheltered or ice-free walkways, sunlit atriums, and balconies or marquees that project out over a sidewalk or entrance, providing cover.

Seems sensible, no? But Shinohara also writes that “a group called the Building Owners and Managers Association has started a petition drive to get the city to kill the massive, seven-year-long, 14-chapter modernization of local zoning laws, of which commercial design standards are part. They want the city to stay with existing code,” which as far as we can tell has pretty much allowed commercial developers to do whatever they want. This is, after all, a notoriously independent part of the country that doesn’t warm to government involvement very easily (except, um, for those timber, oil, and gas subsidies, but that’s another matter).

The proposed code is scheduled to come before the city’s decision-making Assembly for adoption this spring.

Anchorage’s circumstances raise some important issues about how best to improve urban landscapes and urban livability – sometimes in the face of libertarian attitudes about government. More expansively, how best can citizens and their governments, organized by the consent of the governed into a constitutional system aimed at enforcing the responsibilities of citizenship toward the common good, better attain those ends? That’s a mouthful, but the query is aimed at those who will always say, “Not me, buddy. I know what’s best for me. And unless you’re calling to rescue me from my burning building, stay out of my hair, OK?” Such a response is too often engendered whenever new local requirements are proposed, whether necessary to clean up a community’s rivers and streams, keep children out of danger or, heaven forbid, keep truly ugly buildings from proliferating like dandelions in the spring.

But let’s face it: Blank walls running along a city street are ugly, and they’re even dangerous.  They allow for no “eyes on the street,” crucial (by all professional law enforcement accounts) for keeping streets safe. And they’re the architectural equivalent of presenting your backside to the rest of the world – all the time. Lovely.

They allow for no “eyes on the street,” crucial (by all professional law enforcement accounts) for keeping streets safe. And they’re the architectural equivalent of presenting your backside to the rest of the world – all the time. Lovely.

But how do you “legislate” them away? How can a local government best achieve the legitimate aims of enhancing public safety and securing for the benefit of all citizens a more functional, efficient and, yes, attractive community? After all, you can’t pass a law that requires “good taste,” whatever that is. (At least that’s the apparent complaint of some of our architect friends, who fear some draconian curb on their creativity. C’mon. Apart from the fact that form-based codes are themselves the work of gifted architects, maybe it’s that insistence on sculptural freedom and “creative” architecture that sometimes gets us into this fix in the first place. But don’t get us started.)

Regardless of what some might think, most of us do live in communities. And the constitution says that communities have the right – and the responsibility – to provide for the public good, and the general health, safety and welfare of all their citizens. Sometimes that is going to mean that, after a lot of open consideration, an ordinance will be passed that requires citizens to pony up to the mutual responsibilities bar: ‘We [insert name of community] pledge to keep you safe and keep our community livable and economically energetic, while you [insert name of citizen and business alike] pledge to uphold certain standards of behavior and action.’

That’s how we see attempts such as those that Anchorage is making, or similar ones elsewhere, to try to eploy reasonable new zoning standards to improve a city’s image and look, its functionality, walkability, and environmental quality. We elect representatives to make these decisions, and if the process is an honest and open one, we should honor our subsequent responsibilities as citizens.

With respect to Anchorage’s proposed new zoning, no, good taste cannot be legislated. But certain minimum standards and principles can be articulated that express qualitatively or quantitatively how a community wishes to present its face to the world – standards relative to proportionality, bulk and height, scale, location on a street, pedestrian functionality and yes, even how the street-level façade should function. A city might achieve this with a variety or menu of choices, or provide some incentives and disincentives to property owners and developers. (For an interesting presentation showing the issues Anchorage is trying to address, and some modest improvements the new code would encourage, go here. Most of the images in this post are from that presentation.)

The bottom line is that local communities can and should take on, through mechanisms like zoning, how they look, how they function, or how green they become – because the alternative is to succumb to the lowest common denominator, and (as Ian McHarg once said about failing to achieve environmental quality through good planning and zoning) to let the devil take the hindmost.