How LEED-ND identifies the best places for development and planning

Posted September 13, 2010 at 1:34PM

An impressive and thorough, four-part analysis of the Twin Cities metropolitan region demonstrates how the location criteria in the LEED for Neighborhood Development rating system can be used to identify superior places for sustainable development. Not insignificantly, they are found in all parts of the region. The analysis, posted by Brendon Slotterback on his netdensity blog, also indicates which of those locations would benefit from regulatory updating in order to accommodate the kinds of walkable neighborhoods that LEED-ND seeks to encourage.

This provides a replicable model for areas all over the US. It also provides an outstanding blueprint for how the US Department of Housing and Urban Development might apply the LEED-ND criteria to assist its evaluation of applications for discretionary financial aid to housing projects, as HUD Secretary Shaun Donovan promised earlier this year.

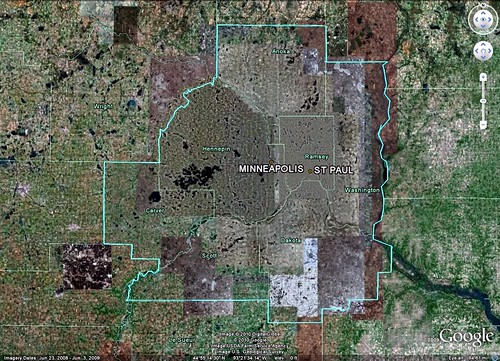

Above is a satellite image of the Minneapolis-St. Paul metropolitan area, a vast, seven-county region stretching some 70 miles both east-west and north-south. Below it are a couple of representative photos: Minneapolis’s Linden Hills neighborhood on the left, and the St. Paul skyline on the right.

The region’s 186 cities and townships comprise large cities, suburbs old and new, small rural towns, farmland, forests and, of course, lakes and rivers. Its population was estimated by the Twin Cities’ Metropolitan Council in 2007 at 2.85 million, though a larger, 11-county combined metropolitan statistical area tracked by the US Census (including two counties in Wisconsin) contained an estimated 3.5 million people as of 2006, ranking it as the country’s 13th most populous. The Metropolitan Council predicts an influx of a million additional residents by 2030 in the seven-county core.

Where and how that growth is accommodated has huge implications for the region’s environment, economy, and social fabric. To find the best locations, Slotterback used a step-by-step approach.

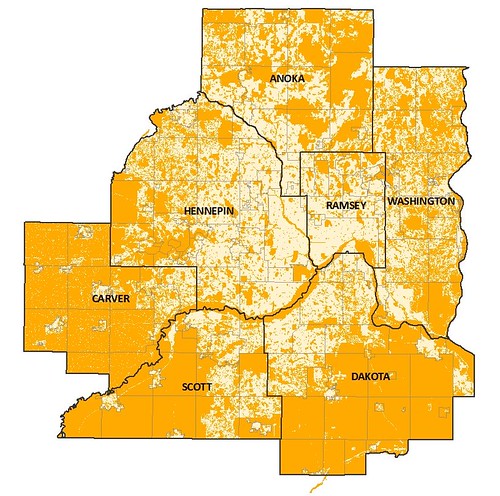

First, he used publicly available spatial data to screen out land likely to be ineligible under the four LEED-ND criteria that exclude from certification certain wildlife habitat; wetlands, water bodies and their buffers; floodplains; and farmland of significance. (He used proxies in some instances.) The combined results of those exclusions are shown above in orange. It looks like a lot, but bear in mind that this is a 70-mile by 70-mile area, and the “likely excluded” areas are generally those not only comprising sensitive lands but also lying at some distance from existing development.

In the next installment, Slotterback applies the “smart location” prerequisite (SLLp1, for LEED-ND junkies) that is the heart of the location criteria. It requires that the site be within an existing or planned water and wastewater service area and also meet one of the following criteria:

- Infill site

- Adjacent and connected to existing development that has at least minimal infrastructure density

- Within walking distance of existing or committed regular transit service

- Proximate to existing neighborhood assets

One can argue that those criteria are too generous to define true smart growth locations, but I won’t rehash that here. Remember that meeting them isn’t sufficient to earn certification credit; it just gets your site in the door.

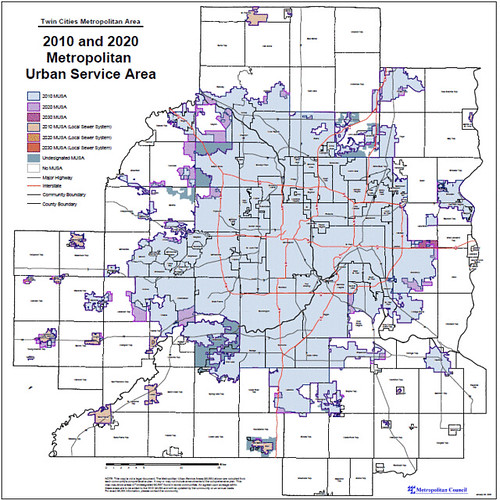

To serve as the screen for existing or planned water and wastewater service areas, Slotterback uses the region’s “metropolitan urban service areas,” as identified by the Metropolitan Council, above. (Note that the color-coding reflects some incremental additions to the MUSAs over time.)

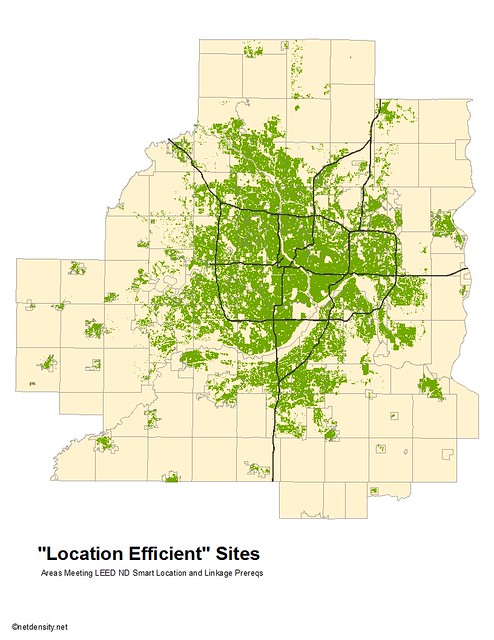

He then applies the infill, adjacency, transit, and neighborhood-asset screens (maps, links and explanations available in his post). The results are shown above: everything in green passes the tests. As Slotterback observes, “in my opinion, a surprising amount of the metro area is eligible.” This should be comforting to developers, architects and planners who feared that LEED-ND would be too restrictive.

In his third and fourth installments, Slotterback gets more sophisticated, delineating not only those locations that are eligible according to the LEED-ND criteria but also those that have the right existing built environment and zoning to be most hospitable to the development design (particularly walkable densities) that LEED-ND requires beyond the location criteria. He calls these locations of "high location efficiency." It is unsurprising (if unfortunate) that many jurisdictions with eligible locations do not yet permit even the minimal densities required by LEED-ND (7 units per acre residential, excluding rights-of-way and non-buildable land; 0.5 floor area ratio commercial).

In the standard-writing “core committee” that constructed LEED-ND, we knew fully well that many good locations for smart urbanism are not currently zoned to accept it. We were not willing to compromise the definitions of smart growth and new urbanism any more than we already had, with the result of giving the honor of certification to substandard development in places with bad zoning. Our hope was that LEED-ND would serve as an impetus for jurisdictions to update their codes accordingly.

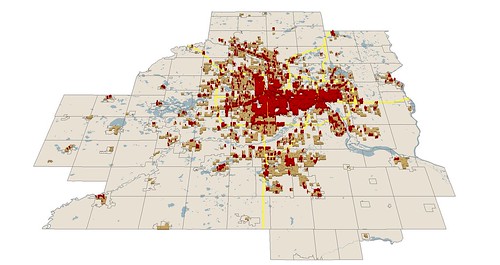

That is exactly what Slotterback recommends. The map just above indicates which locations are currently LEED-ND ready (in red) and which should undergo regulatory updating to become so (in amber). While even some of the far-flung areas have portions shown to be ready, the effect is that his approach not only indicates those places in the Twin Cities region where future development should be channeled but also where authorities should focus planning and zoning attention.

This is terrific. Slotterback summarizes the benefit of LEED-ND as a planning tool:

“I would argue that we can also use LEED ND as a guide for growing our region more sustainably. The requirements of the rating system can show us where it would be appropriate to target future growth, what areas should be preserved until sufficient infrastructure is available, and what areas are totally off-limits.”

The final installment also offers recommendations to assist the process. My own recommendation is that interested readers look at the entire series, which has a lot more substance than I can present here.

Slotterback’s methodology has much in common with that employed by Criterion Planners for the same purposes, which we highlighted here and here. I have long been a fan of Criterion’s inspiring work, and regions and municipalities might be well-served by examining both to see if their jurisdictions' data sets are better accommodated by one or the other.

One of the things that I especially like about Slotterback’s analysis is that the graphics plainly illustrate that, contrary to popular myth, suburbs and even small, rural towns have locations suited to smart growth development as defined in LEED-ND. I will have much more to say about that tomorrow.

Move your cursor over the images for credit information.