Geography of housing recovery favors cities and walkable neighborhoods

Posted October 26, 2011 at 1:33PM

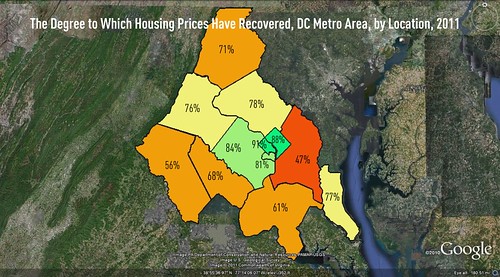

The map just above shows the degree to which twelve jurisdictions in the Washington, DC metropolitan area have experienced a housing recovery. In particular, the percentages reflect how the August 2011 average home sales price in each city or county compares to the average sales price experienced in each at the peak of the region’s housing market, in November 2005. The numbers, which were published in The Washington Post earlier this month, are based on research by the George Mason University Center for Regional Analysis.

While no part of the region has fully recovered, the degree to which they have rebounded varies significantly from one jurisdiction to another. Kimberly Lankford, a freelance writer on assignment for the Post, noted in the story that “in general, the farther you travel from downtown Washington, the slower the recovery has been.”

Indeed. The strongest recoveries have been made in the central city of Washington and neighboring Arlington, Virginia, the region’s most urban jurisdictions, both filled with walkable neighborhoods.

Convenience matters to homebuyers. On average, travel distances are shorter in central jurisdictions and transit, biking and walking alternatives to driving more plentiful; jobs, shopping and amenities are likely to be closer. Density tends to be higher, although both DC and Arlington have plenty of single-family homes. The two jurisdictions that have made the next strongest recoveries are Alexandria and Fairfax County in Virginia, both relatively close to Washington and each a mixture of urban and suburban areas.

Convenience matters to homebuyers. On average, travel distances are shorter in central jurisdictions and transit, biking and walking alternatives to driving more plentiful; jobs, shopping and amenities are likely to be closer. Density tends to be higher, although both DC and Arlington have plenty of single-family homes. The two jurisdictions that have made the next strongest recoveries are Alexandria and Fairfax County in Virginia, both relatively close to Washington and each a mixture of urban and suburban areas.

This is consistent with mapping that I have done in the past showing that, during the slump, housing prices in close-in locations came the closest to holding their value or even increasing, while outer locations suffered. These new numbers, though, by expressing the changes as percentages of average prices six years ago, illustrate the extent to which the market has shifted since the peak. Basically, a significantly larger number of buyers want smart growth locations now than they did then. That’s a trend.

The jurisdictions that have fared the worst are all substantially outlying, with one very important exception: Prince George’s County, Maryland, the region’s poorest county and, of the suburban jurisdictions, the only one with a majority African-American population. Prince George’s average home sales prices today are only at 47.4 percent of where they were in 2005. Ouch. While it comes as no surprise that PG County has a weak market compared to more affluent jurisdictions, I am surprised that it is so much weaker when compared not to other jurisdictions but to itself several years ago. I can’t help but wonder if there were unusual factors that inflated the 2005 prices, making today’s seem so much weaker by comparison. In any event, PG is the only exception to the general rule that buyers’ preferences have shifted to close-in, urban locations.

Many in the business would seem to agree that the way forward is with more smart growth and urbanism. In The Oregonian, Elliot Njus profiles Renaissance Homes, a metro Portland builder that has been shifting from an overwhelmingly suburban portfolio to the production of more infill homes in the city of Portland. In 2006, none of the company’s new homes were in the city; now two-thirds are. The change in direction was prompted by the need for a sounder business plan after the company filed for bankruptcy in 2008. "You're not going to see us in [suburban] Gresham or Forest Grove anymore," company president Randy Sebastian told Njus. "That's not where our customers want to be."

Many in the business would seem to agree that the way forward is with more smart growth and urbanism. In The Oregonian, Elliot Njus profiles Renaissance Homes, a metro Portland builder that has been shifting from an overwhelmingly suburban portfolio to the production of more infill homes in the city of Portland. In 2006, none of the company’s new homes were in the city; now two-thirds are. The change in direction was prompted by the need for a sounder business plan after the company filed for bankruptcy in 2008. "You're not going to see us in [suburban] Gresham or Forest Grove anymore," company president Randy Sebastian told Njus. "That's not where our customers want to be."

One might make a case that these are exceptions, with Washington an unusually resilient housing market compared to other parts of the country and Portland being, well, Portland. But it’s not the case: Sam Newberg writes in Urban Land that there is a national trend not only toward more urban locations but also to multifamily properties. The strongest market right now is for rental apartments in central locations, writes Newberg:

“Renters of all ages want to be in walkable, connected locations. Markets such as Chicago, Seattle, San Francisco, and Minneapolis are experiencing most demand for apartments in core city locations. Denver has seen demand near light rail stations. In Minneapolis, the Cassidy Turley 2011 Annual Market Report indicates that most demand for new housing is in the two core areas of Minneapolis and St. Paul, with fully 73 percent of all proposed apartment units to be located there.”

These reports are fully consistent with another national trend, toward less driving. Writing in the Canadian newspaper The Globe and Mail, Anita Elash observes that “the distance driven by Americans per capita each year flatlined at the turn of the century and has been dropping for six years. By last spring, Americans were driving the same distance as they had in 1998."

Elash questions whether we are reaching the point where the amount of driving by the nation as a whole has irrevocably stopped growing:

“If developed countries are reaching ‘peak car,’ as some transportation experts are calling it, it's not just a product of high unemployment or skyrocketing fuel prices, as the pattern began to show up years before the 2008 financial crisis . . .

“Indeed, the shift is so gradual and widespread that it's clearly not a product of any ‘war on the car’ or other ideological campaign. Rather, it's a byproduct of a stage of development that cities were probably destined to reach ever since the dawn of the automobile age: Finding themselves caught in an uncomfortable tangle of urban sprawl, population growth and plain individual inconvenience, people, one by one, are just quietly opting out.”

Elash cites the demographic convergence of the millennial generation coming of age at the same time that baby boomers are retiring, reducing driving and, in many cases, downsizing. Both of these two largest generations in American history present a strong market for walkable environments that stress convenience. By contrast, married couples with children, the strongest market for traditional suburban living, are decreasing as a portion of the overall housing market. These points are often made by analysts such as Arthur C. (Chris) Nelson of the University of Utah, my friend and market analyst Laurie Volk of Zimmerman/Volk Associates, and the market research firm Robert Charles Lesser & Company, which has found that 77 percent of millennials plan to live in an urban core.

Does all this mean that there is no more demand for suburban housing and SUVs? Hardly. But, as Nelson has often said, there may already be enough supply of large-lot housing to satisfy future demand. The growth in the market – in the DC area and elsewhere – is toward walkable neighborhoods and convenient, central locations. This is good news for cities and, ultimately, for the planet.

Move your cursor over the images for credit information.