Sustainability in the crazy-quilt world of metro regions

Posted April 30, 2012 at 2:15PM

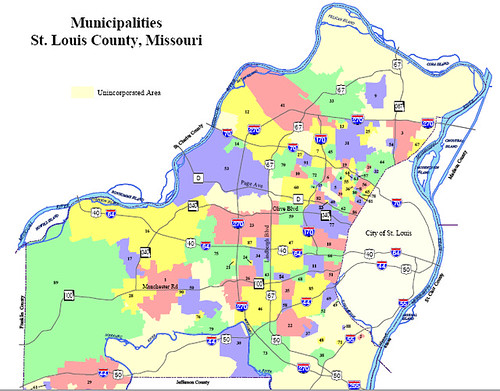

Our highly fragmented "system" of local governments makes it nearly impossible to address important issues facing metropolitan America in a rational way. Indeed, just getting around a metro region can be a challenge. Let's look at some examples.

Getting there from here shouldn't be this hard

I recently had the opportunity to review a draft student paper on the difficulties posed by metro regions where cooperation among governments and service providers is poor. (Which, unfortunately, describes almost all of them.) The student’s opening account of public transportation connections between an inner-ring suburb in New Jersey and Center City Philadelphia was striking:

“As the crow flies, 36th Street Station [on the border between Camden and Pennsauken, New Jersey] lies roughly 4.5 miles from Philadelphia City Hall, and roughly 5.5 miles from Philadelphia’s 30th Street Station, the nation’s third busiest Amtrak station and the center of Philadelphia’s SEPTA [South Eastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority] commuter rail system (versus roughly 6 miles and 7.3 miles via road transport, respectively). If one wants to travel rapidly via public transit from the neighborhood served by 36th Street Station in New Jersey to either Center City Philadelphia or 30th Street Station, however, the options are grim . . .

“In order to get from 36th Street Station on the Camden/Pennsauken border to 30th Street Station in Philadelphia, one must take light rail operated by NJTransit; the PATCO High-Speed Line operated by a subsidiary of the Delaware River Port Authority of Pennsylvania and New Jersey; and the Market-Frankford heavy rail line operated by SEPTA. Separate ticket purchases will be required for each.”

It will take close to an hour under normal circumstances to traverse those five miles via transit, not counting walk time.

The requirement to buy three separate tickets for what should be a simple commuting journey seems frustratingly quaint in the high-tech world of the 21st century. Yet, it’s not all that surprising given the intense jurisdictional fragmentation within our metropolitan areas. The Philadelphia-Camden metropolitan area, according to The Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission, comprises two states, nine counties, and a staggering 353 municipalities. No wonder transit systems are fragmented as well.

The limits of MPOs

The Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission is charged with responsibility for “the orderly growth and development of the region.” Anyone want to venture a guess as to its chances for success at that goal? The track record doesn’t give much cause for hope: The Commission was formed in 1965; but, from 1970 through 2000, the region grew a modest six percent in population, while growing about 44 percent in developed land. That doesn’t sound too “orderly” to me. (I don’t have more up-to-date numbers handy; but I suspect the disparity between population growth and growth in land consumption has only gotten worse.)

By the way, I don’t blame metropolitan planning organizations like DVRPC for the failure to get a handle on growth patterns. For the most part, they do great work, and a fantastic job at data collection and sharing. More than any other group of local public entities in the US, they understand the important economic and environmental issues of the day at the scale that matters most.

I just wish they had more authority. Especially when it comes to land use, MPOs are basically advisory, and their ability to influence what jurisdictions within their purview choose to do with regard to transportation, economic development, and other matters of great import tends to be extremely limited.

In short, the jurisdictional boundaries of our municipalities are basically relics of history that bear almost no current relationship to how the economy or the environment actually operates. As a result, our crazy-quilt system of local government is seriously outmoded in most of America. Dysfunctional transportation is only one of the consequences, but it’s a good place to start.

Being polycentric complicates things even more

Writing in his excellent “Shaping the City” column for The Washington Post, architect and urban sage Roger Lewis notes that the Washington, DC metro region has now become polycentric, with important concentrations of jobs and economic activity scattered all across the region.  This is something no one anticipated when our basic transportation systems were planned and constructed. The region has excellent rail transit within the Metro system, for example, but it was planned at a time when suburbs were “bedroom communities” where people went home after their jobs in the city. That isn't today's reality: while the system is great at connecting many suburbs with downtown DC, Metro is largely irrelevant when it comes to the suburb-to-suburb travel that reflects current geographic and economic conditions in the area.

This is something no one anticipated when our basic transportation systems were planned and constructed. The region has excellent rail transit within the Metro system, for example, but it was planned at a time when suburbs were “bedroom communities” where people went home after their jobs in the city. That isn't today's reality: while the system is great at connecting many suburbs with downtown DC, Metro is largely irrelevant when it comes to the suburb-to-suburb travel that reflects current geographic and economic conditions in the area.

And it’s not just transportation. Lewis elaborates:

“Explore greater Washington — Prince George’s, Montgomery, Arlington and Fairfax counties and Alexandria. You will see numerous formerly suburban areas that are becoming denser and more urban, and ultimately more urbane. However, making this future polycentric metropolitan region really great will depend above all on developing an effective, region-wide system of transportation tying these areas together.

“It also will depend on more affordable housing opportunities across the region for an expanding, increasingly mobile workforce; more business and institutional employment opportunities throughout the region; greatly improved elementary and secondary education in all the region’s jurisdictions; and improvements in preserving and sustaining the region’s environmental assets.

“Achieving all this is challenging in a region so jurisdictionally fragmented and governed: two politically disparate states encompassing multiple counties and municipalities surrounding the national capital, a federal district that is a hybrid between being a state and a city. Yet the region’s evolution as a polycentric metropolis is partly attributable to this fragmented political structure. Each jurisdiction can shape its geographic domain as it sees fit, largely independent of what nearby jurisdictions are doing.”

Hubs of jobs and economic activity around metro Washington, DC

The greater DC region does have a multi-jurisdictional rail and bus transit system - the Washington Area Metropolitan Transit Authority - that serves all the adjacent counties as well as the central city. (It also has a number of sub-regional bus systems.) But, as Lewis points out, WMATA is controlled and funded by the various jurisdictions, whose parochial interests can undermine the system’s ability to respond to regional needs.

Parochialism and caprice

The Commonwealth of Virginia’s commitment to Metro’s new Silver Line, for example, has been somewhat wavering, as reflected in decisions to (1) forego underground stations that could greatly assist walkability in the potentially transformative makeover of the Tysons Corner area, currently one of the nation’s most notoriously sprawling, and (2) depart from plans to build the station at Dulles International Airport too far from the terminal for most passengers to comfortably walk. The first half of the line is already under construction, but recent reports suggest that state legislators and county supervisors in Virginia have backed away from their commitment to paying their portion of funding for completing the Silver Line to Dulles at all. Never mind that the federal government is providing most of the cost or that Virginia has had no hesitation in building costly additional lanes for car and truck traffic on the Capital Beltway.

Added on edit: Indeed, Dana Hedgpath writes in today's Washington Post that the long-planned Silver Line segment could now be "dead" because of inter-jurisdictional chest-puffing:

"After more than 10 years of planning to add 23 miles of Metro rail line in Northern Virginia, the second part of the Silver Line project could be dead before a spade of dirt is turned.

"The Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority, Virginia, and Loudoun and Fairfax counties are at a stalemate over pro-union labor deals, concerns about costs and an inspector general’s investigation of the authority."

This is local government in action, warts and all.

In another column, written two years ago, Roger Lewis praised the DC region’s MPO – the Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments – for good planning and advocacy. But he was astutely clear-eyed about the obstacles to actually getting things done for the region:

“Goals include preserving and enhancing established neighborhoods; creating transit-oriented, mixed-use communities and dense, walkable activity centers; providing more transportation connectivity and choices; maximizing environmental protection; and reducing energy use and greenhouse-gas emissions . . .

“[But] members of COG and the Greater Washington 2050 Coalition understand that, in addition to local political obstacles, many demographic, fiscal and regulatory obstacles exist within and between jurisdictions. There are substantive differences in zoning laws, budgets, tax and spending policies, economic conditions and cultural characteristics. In fact, the cities and counties in metropolitan Washington directly compete with one another for new business and investment and regularly vie for federal and state funds.”

Attempts at regional cooperation

There are a few examples of good regional cooperation around the country. Portland, Oregon has the nation’s only directly elected regional government, Metro, with legal authority over regional land use, transportation, and other specified issues in three counties and 25 cities. The region’s success in containing sprawl, preserving forests and farmland, redevelopment, and efficient transportation is renowned, in part because of the regional authority. But Metro’s jurisdiction does not extend to those parts of the Portland region across the Columbia River in Washington, which lag behind their Oregon neighbors in addressing these issues.

Taking another approach, the seven counties that compose Minnesota’s Twin Cities region share tax revenues. Forty percent of each county’s property tax is redistributed within the region based on population. This tends to reduce somewhat the fiscal disparities among jurisdictions and dampen intra-region competition for businesses and development. The region’s Metropolitan Council is a bit of a hybrid, with more limited powers than Portland’s Metro but more influence than most MPOs over issues such as wastewater, parks, transit and, through grantmaking, revitalization and economic development.

Perhaps the new frontier for regionalism in the US is being presented by California’s innovative planning law to reduce pollution of greenhouse gases, SB 375. That law relies primarily on metropolitan regions for its implementation, empowering MPOs to exercise greater influence over regional land use and transportation investment through Sustainable Communities Strategies required from each to meet state-imposed emissions reductions targets. It also provides significant economic and regulatory incentives to assist compliance. SB 375 is now beginning to produce some very promising regional plans.

What all these approaches have in common is a chipping away at the morass of challenges presented by the dysfunction inherent in fragmented local jurisdictions. I commend them, but we’re still a long way from where we need to be. None would appear as strong as, say, Ontario’s Places to Grow regime for getting control of land use and transportation in the Toronto-Hamilton region. Even Ontario’s system is encountering implementation challenges, and critics argue that some of its standards are too weak, but it is conceptually stronger than anything south of the border. The strong culture of individual property rights and hyperlocal control that prevails in the US suggests that our states and regions are unlikely to become much bolder anytime soon.

That does, however, leave one mechanism for regional cooperation not covered above: voluntary agreements among disparate jurisdictions to take joint action for the common good. Tomorrow, we’ll look at an example.

Related posts:

- The economic importance of metro regions (July 25, 2011)

- The importance of regional planning that matters (August 12, 2011)

- Nashville's promise for a greener transportation future (February 15, 2012)

- Bringing regions together for cooperation and planning would promote sustainability (March 6, 2009)

Move your cursor over the images for credit information.