Getting to yes on the right kind of suburban change (by Lee Epstein)

Posted October 9, 2012 at 1:25PM

Today’s article is by my friend Lee Epstein, an attorney and land use planner working for sustainability in the Mid-Atlantic region. Lee’s last contribution here was “The fall - and rise - of small downtown America.”

Many of us involved in the creation or advocacy of “sustainable” cities, neighborhoods and metro regions know what we’re mostly for. That would be communities that:

- Grow first within the existing development footprint, taking advantage of existing public infrastructure

- Integrate functional green space for air, light, recreation, beauty, and stormwater management

- Improve public transit, bike accessibility and walkability

- Encourage a healthy mix of land uses and activities – and

- Embrace a somewhat higher (though not necessarily high, depending upon location) residential and commercial density.

And we also know what we’re mostly against. That would be:

- Development that gobbles up working lands and open space, ever-outward in pods of self-replicating sprawl

- Otherwise “urban” and urbanizing development that wastes opportunities to grow in their communities’ central places – and

- Towns and cities that fail to invest in up-to-date infrastructure that encourages sensitive revitalization, uses environmental resources efficiently, permits fast internet services, or that would, with a bit of foresight, allow public transit to expand and walking and biking to thrive.

Suburban preferences are real, if also sometimes elusive

The problem is this: how do we get to the “promised land” of the first set of characteristics, and avoid the second, especially in the suburbs? Among the most difficult conundrums today is that many people distrust the former group of actions and attributes, while accepting the latter as standard practice. This group of doubters does not include everyone, of course: committed city-dwellers wouldn’t think of living anywhere else, and intuitively understand some of the advantages of their chosen lifestyle. (They also fully understand some of the current disadvantages as well: somewhat smaller living spaces and mostly public but not as much private open space; sometimes, but not always, higher living expenses and maybe, but not always, somewhat higher crime rates; and, as of yet, public school systems that may be underperforming). Housing prices per square foot in cities are higher, on average, compared to those in suburbs precisely because there is such high demand for centrally located, urban environments.

But oftentimes suburbanites are equally committed to their lifestyles. They like their houses and big yards. They like shopping – for everything – by car. Sometimes they don’t even mind a long commute to work by private automobile. And (in part because of at least forty years of economic segregation), they like their kids’ suburban school systems.

What some folks in suburbia (or even exurbia) eventually come to see, however, is that in many places across the US, the lifestyle they thought they were choosing comes at a price and is soon compromised by their subdivisions’ own set of changes. The inner suburbs are already looking more and more like their central cities, not only physically but also in terms of those places’ economic and social problems. Indeed, as central cities are making a pronounced comeback, some inner suburbs are now suffering more of the challenges we have long associated with inner cities than are the inner cities themselves. The outer suburbs, for their part, are beginning to take on some of these characteristics as well, although in a more haphazard way, here and there, but not there and here.

Some may seek to escape these changes by moving even farther out into what was once the rural countryside. That may buy a few years of something closer to the suburban ideal, but maybe only in one’s particular house and yard: the shopping requires longer (and increasingly more expensive) drives, to say nothing of those required by employment, or by visiting family and friends. Time is eaten up by lengthy trips; we know of cases in metropolitan Washington where workers sleep in a hotel or friends’ house closer to work just in order to be on time for a meeting the next morning; meanwhile the spouse and kids out in the house on the fringe are left on their own for the night.

Additionally, of course, if suburbs and exurbs continue to sprawl outward nearly without limits, a city, county, or larger region can lose its identity, squander the surrounding beauty and function of its resource lands, and bear significant environmental costs. Moving closer to nature by settling in the outer suburbs works only if you’re among the last to do so.

Trends in suburbia

Urban scholar, real estate analyst and developer Christopher Leinberger analyzed some of these changes more than a decade ago, when he described three concentric rings or generations of urban progression and disinvestment that were altering the face of the suburbs. But the suburbs “continued to grow at breakneck speed,” he noted in an article in The Atlantic in 2008. Leinberger has more recently been studying an important countervailing trend: the quite significant movement by the millennial generation out of the suburbs where they grew up and back into the cities that their grandparents left. This is one reason why central-city real estate generally held its value during the Great Recession or declined relatively little while many fringe suburbs experienced devastating loss and decline.

Leinberger has also studied the maturation of some of journalist and urban observer Joel Garreau’s “edge cities” into “walkable urban places” – though in many locations these have become not quite city, not quite suburb, with the most desirable characteristics of neither. (Twenty years ago Garreau’s now-iconic book Edge City chronicled the leapfrogging formation of dense but chaotic workplace and commercial “centers” on what was then the urban fringe. Both these and so-called suburban “lifestyle centers”-- somewhat artificial mock-ups of traditional, walkable Main Streets, generally surrounded by parking lots -- are still showing some marketplace strength in places as they “grow up.”)

What all this is saying to me is that the face of our suburbs is changing whether some of us like it or not. The real question is this: can suburban residents come to see a difference between good change and bad change, and come to embrace the former in order to eschew the latter?

The personal experience of suburban change

A confession: I am among those suburban residents. When my family grew from three to four, twenty years ago, we couldn’t shoehorn another warm body into our little bungalow, and we couldn’t afford to buy a bigger house in the little town in which we lived or the bigger city nearby. There also were job location issues, so we were forced to move outward by a couple of miles, to an inner suburb. It’s not been all bad: we love our neighbors, we can hike in the hundreds of acres of a stream valley park system, and our kids walked to school. But we still like city life and may move back into town when it’s practical.

So, why am I now focused on suburban change? There’s a small commercial strip near us. Typical of many, it’s kind of run down, and when a sizeable space recently opened up for lease, I opined on the neighborhood list-serve that it would be great to get a nice restaurant there to which we could walk. “Wouldn’t it be nice,” I continued, “if we could reach more destinations by being able to walk or take a convenient bus to them, instead of having to drive everywhere?”

Well, the can of worms I opened wasn’t your normal 15-ounce size, but more like a gallon: “If we wanted to live in THE CITY [which was written in caps] we would have moved there! We don’t want to turn our area into ______ [a nearby, more urban and up-scale community],” noted one fairly hysterical response. “We like our space, and we don’t mind driving to the grocery store or to _____ for a nice meal once in a while.”

“But how about a little more mixing of land uses?” I asked. “No way,” was the response from many. “It’s quiet here,” someone said – as if a coffee shop or a doctor’s office would convert our little Brigadoon into Manhattan. “But our suburbs are already changing,” I said. A wooden cross and a garlic necklace should hold that off, seemed to be the unspoken response.

And that’s the problem. Whether it’s intensifying an already urban residential neighborhood with a new mid-rise apartment or office building or a new business, or encouraging the suburbs to grow up primarily with infill and the increased convenience of even a modest mix of new land uses as the area naturally becomes more urban, the responses usually are, “We like things the way they are,” or “It will alter the character of our neighborhood,” or “Who knows what kinds of people [the change] would bring.”

It is human nature to be suspicious of change – and, heaven knows, we have seen enough horrible changes to our communities in the last few decades to reinforce that instinct. In addition, some folks honestly prefer the scale and nature of 1970s suburbia; within reason, we can respect those preferences (though we shouldn’t feed them with more and more and more of that pattern without figuring in its true cost). That’s why God made a whole box of Crayola colors rather than one or two.

Replacing fear with facts and involvement

For many people, however, it just comes down to fear of change and fear of fear. For these folks, I believe the best way to meet fear is with honest, open communication and solid information. It’s up to those of us who want to manage change, and to local governments, to provide straightforward explanations about at least the following things:

- What kinds of changes are already occurring

- How local neighborhoods have choices about how to shape those changes (but seldom to prevent them entirely)

- In what ways some modest redesign of our neighborhoods can provide us with a higher quality of life – and, importantly,

- How to fully participate in the public conversation that needs to take place before change occurs.

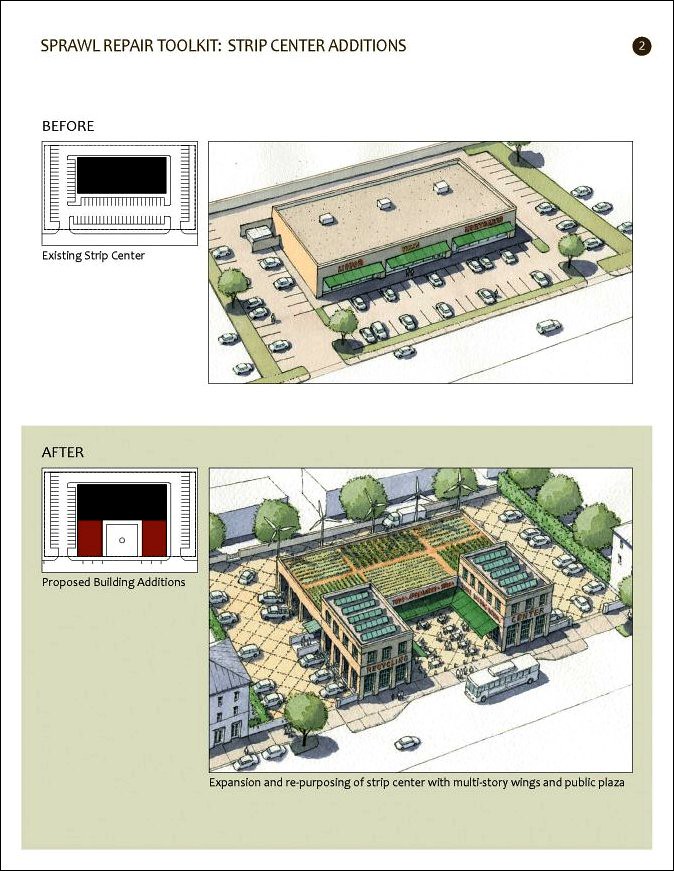

The way that such information is presented is important. Some people learn best by hearing, others by seeing; it’s been my experience that good, accurate visual images go a long way to assuaging fears that some infill development will convert one’s cozy little corner of suburbia into Chicago’s Loop. The advantages of compact, sustainable, infill growth are legion; however, as much as some of us may like to think so, they are not self-evident.

Other groups can fruitfully be brought into the circle to lend an ear and maybe a hand: churches (which can wield significant influence in some places), the public school system (including local PTAs), and civic clubs and organizations, for example. Even small local environmental groups – such as river and watershed advocates, garden clubs, and the local Sierra Club or Audubon chapters – can and should be brought into the conversation, but with facts and choices rather than fear-mongering. Otherwise, they are more likely than not to turn into opponents.

So that’s my prescription. I know it sounds kind of simple, but I don’t know any other way to soften hearts and possibly change minds. If infill development – done right -- presents our best shot at reducing the conversion of farm and forest, stream valley and wetland, mountainside and wide open spaces, into half- (or two-, five- or even ten-acre) lots, and in reducing the driving that will come with it, then it has to be adequately explained, promoted and understood. Otherwise, neighbors just like some of mine will resist it… every, single time.

Related posts:

- How to retrofit failing suburban big-box stores into a green showcase (March 12, 2012)

- Fixing suburbs with green streets that accommodate everyone (December 20, 2011)

- Can grassroots planning save what's best of a rapidly suburbanizing community? (December 9, 2011)

- Is it over for suburban corporate campuses? (May 31, 2011)

- Remaking a suburb for the creative class (October 21, 2010)

- How immigrants are revitalizing America’s fading suburbs (April 23, 2010)

- Brookings: The suburbs as we think of them are vanishing (January 23, 2009)

- More on suburban retrofit, from the NY Times (January 12, 2009)

Move your cursor over the images for credit information.