An affordable housing enclave that fits in, strengthens a neighborhood, and protects the environment

Posted January 14, 2013 at 1:34PM

A group of civic and architectural partners in Little Rock has developed a great concept for improving a declining neighborhood, incrementally increasing density, and applying advanced measures for stormwater control at the same time. All this in a single-family, affordable infill development with first-rate design. No wonder it has won a slew of awards, including a 2013 national honor award from the American Institute of Architects for regional and urban design.

The project employs the “pocket neighborhood” concept championed by architect Ross Chapin – reducing the footprint of a group of smaller, single-family homes by sharing gardens and amenities that would occupy more land if duplicated for each individual house. Chapin, who has worked mainly in the Pacific Northwest, gives his projects high-quality building materials and beautiful design features that respect their neighborhood settings. I’ve been a fan since before I knew the concept had a name, when I ran across his pioneering and lovely Third Street Cottages in Langley, Washington. I love incremental approaches to increasing density, in part because they seldom require major lifestyle changes and in part because their relatively harmonious design improvements can be somewhat easier to sell to suspicious neighbors inclined to distrust change.

The pocket neighborhood approach is not for everyone, though; in fact, as I learned while teaching a course in sustainable communities at George Washington University Law School, it may not always appeal even to audiences already disposed to favor environmentally progressive approaches. When I showed the students Chapin’s designs for an in-town enclave some 10 miles north of downtown Seattle, they disdained them as too suburban and expensive.

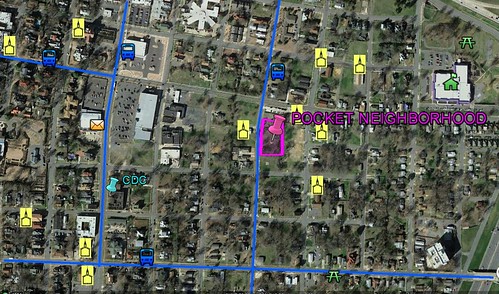

The good news is that Little Rock’s Pettaway Pocket Neighborhood retains all the good aspects of Chapin’s concept while curing the aspects that troubled my students. Far from a suburban location, the site on the Arkansas capital’s Rock Street is a 10-minute walk (0.5 miles), according to Google Maps, from the governor’s mansion, and only about a mile to the heart of downtown. The site enjoys a Walk Score of 77, being within a quarter mile of at least one restaurant, grocer, park, school, and health care clinic (I didn’t count how many of each). As you can see from the satellite image, the site is also proximate to an amazing number of places of worship. There are three bus lines nearby, though Little Rock’s system is not known for frequency of service.

As I’ve stressed in previous articles, a central location generally means reduced rates of driving, not only because walking and transit are more viable but also because driving trips are shorter, releasing lower levels of carbon emissions. The wonderful Abogo calculator from the Congress for the Neighborhood Technology indicates that households in the Pettaway site’s neighborhood emit only half as much carbon for transportation, on average, as do households in metro Little Rock as a whole. The gridded pattern of well-connected streets further enhances walkability and reduces driving.

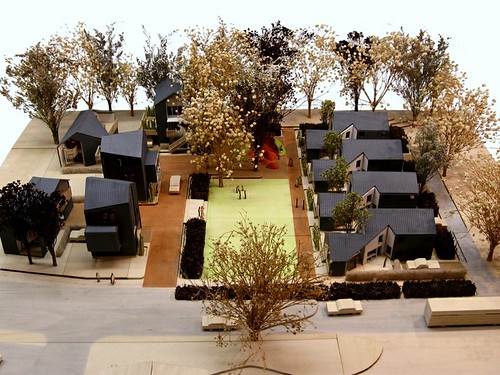

The site plan places nine homes around shared green space and amenities on a one-acre assembly of five parcels. This essentially doubles the density previously contemplated for the site. According to a press release, the homes average 1,200 square feet – not large by American standards, but in line with trends favoring smaller home sizes that appeal to a growing market share – and have two to three bedrooms each. Affordable pricing – about $100,000 – comes from standardized dimensions and materials. Designers chose structured insulated panels and a few types of windows in various configurations.

The size of the homes is important because it represents the so-called “missing middle” between the larger homes that captured the US market in recent decades and the much smaller ones typically found in multifamily dwellings or the trendy but still miniscule (pun unintended but acknowledged) portion of the market claimed by cottages and the so-called “tiny house” movement. For many decades, bungalows of a thousand or so square feet were quite typical for American households, but very little such housing has been built since the 1940s.

Once a lively 20th-century streetcar neighborhood, Little Rock’s Pettaway has since taken a turn for the worse. The Pettaway Neighborhood Manual reports that 26.3 percent of the district’s residents live in poverty, approaching double the 14.3 percent rate for the city as a whole. The satellite view shows many vacant lots, and over 30 percent of the neighborhood is said to be vacant and abandoned.

The Pettaway pocket housing project was a collaboration between fifth-year architecture students in the University of Arkansas School of Architecture and the University’s Community Design Center, an outreach program of the school. It was commissioned by the Downtown Little Rock Community Development Corporation, in partial fulfillment of a planning grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, with additional funding from the city of Little Rock.

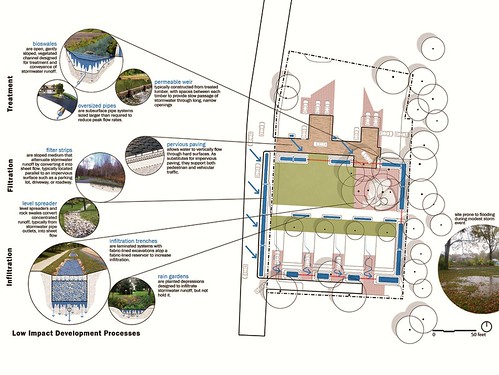

For the pocket neighborhood, designers took resources typically found in individual private lots and pooled them to create a true public realm, something notoriously lacking in modern American residential subdivisions. Shared features include a community lawn and playground, community gardens, a shared street, and a sophisticated but low-impact stormwater management system based on the use of green infrastructure – landscaping and fixtures designed to take advantage of natural rainfall filtration and avoid polluted runoff into the sewer system. Water management is especially important to this site, which has been prone to flooding in past storms.

It is hard to read the small font in the image presenting the green infrastructure features, but it depicts an array of elements working together:

- Bioswales to covey waterflow into the soil rather than out to the street

- Lamination trenches underneath bioswales for better absorption

- Filter strips adjacent to paved surfaces to catch water that would otherwise run off

- Rain gardens that enhance the site with attractive vegetation as the water filters through

- Permeable weirs at selected locations to slow the rate of flow

The idea of clustering homes around a common courtyard or garden didn't originate with Chapin's pocket neighborhoods, of course. It's been around for centuries and has been a staple of multifamily housing and townhomes, in particular. But the concept has been much less common in single-family, detached neighborhoods, particularly those built in the latter half of the 20th century before a few smart growth and new urbanist architects began to bring them back. They make a lot of sense now, helpful to conserving land and encouraging walkability for the growing part of the market that is not seeking a large amount of space.

In Pettaway, the students worked with a citizen advisory committee who, among other preferences, wished to avoid flat roofs or metal siding – nothing “aggressively modern,” according to Stephen Luoni, director of the Community Design Center. The designers looked for ways to blend traditional architectural elements – porches, balconies, terraces, pitched roofs – with modern principles – open floor plans, abundant light, natural airflow, refined choice of materials. I like what I can see of the results – a fresh look, but one in harmony with the scale and character of period housing in the neighborhood. At least one awards jury referred to the design as a “community within a neighborhood,” and that looks exactly right to me.

Even better, the pocket neighborhood could be just the beginning. There is a larger revitalization plan in the works for Pettaway. The Neighborhood Revitalization Manual mentioned above was commissioned by the same set of partners and elaborates a set of excellent principles for restoring the surrounding district. The goal is to bring completeness and ambition again to this once-thriving area whose proximity to downtown positions it well for a revival, and to do so without displacing current residents. Among the concepts discussed in the Manual are a master plan, a form-based code, improvements to walkability, and high-quality infill development.

In my professional world of environmental advocacy, we are encouraged to set our sights on grand, comprehensive schemes that, so the theory goes, will result in major payoffs. Strategic planning exercises and funding guidelines demand that we do so. But there's a problem with this: grand schemes – particularly those that require significant changes in public policy – can take decades to realize, if they come about at all. Meanwhile, actual opportunities for real change in real neighborhoods, where things get built every single day, lie right under our noses. If we ignore them, the grander schemes become moot.

Plenty of advocates work on the big issues (climate change, fracking, disappearing wildlife, and so on), as well they should. These matters are hugely important to our survival. But, in my own writing, I also try to look for smaller measures of progress that can serve as models in the here and now, and bring them to light so others may emulate them. The Pettaway Pocket Neighborhood is a great example of exactly that.

Thanks to George Osner for pointing me to the AIA awards and, thus, to this story.

Related posts:

- Smaller, more sustainable living in neighborhoods that fit in (January 3, 2012)

- How to use LEED-ND to improve an older neighborhood (October 16, 2012)

- "Katrina Cottages" find post-Katrina uses as affordable housing, educational facilities, offices, & more (July 11, 2011)

- The case for living small (August 16, 2010)

- “Smaller homes, urban lifestyles and sustainable communities will shape development” (February 9, 2010)

- Smaller cities can benefit from revitalization, too (September 9, 2009)

- Pocket-sized smart growth (February 26, 2008)

Move your cursor over the images for credit information.