Are Main Streets a thing of the past? Is that OK?

Posted February 4, 2013 at 1:33PM

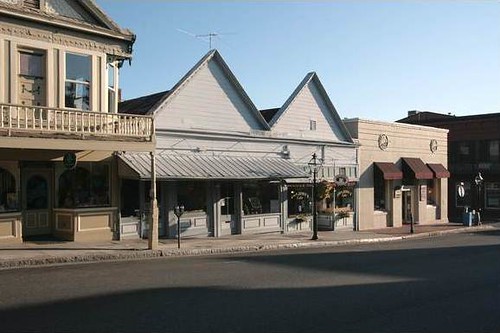

As someone whose job is to promote sustainability in our communities, I sometimes think the traditional American Main Street is a terrific model worth preserving and emulating. It meets so many of the basic aspirations of smart growth: it’s walkable, compact, centrally located, with many types of shops and services integrated together, usually with places to live on upper floors or in houses a short walk away. It has a human scale, neither skyscrapers nor sprawl but something in between. Does the past point the way to a more sustainable future? Some smart observers strongly believe so.

But, when it comes to “Main Street,” the definition can get a little fuzzy. The Cambridge Dictionary of Essential American English is as good a place as any to start: Main Street is “the main road in the middle of a town where there are stores and other businesses.” The Oxford English Dictionary cites usages going back as far as 1598. When those of us in the field of placemaking use the phrase, we’re generally thinking of the kind of shopping districts that used to serve smaller towns and cities. Frequently the shops and services were aligned adjacent or close to each other along the most prominent street in town, which many places literally called Main Street.

But today, “Main Street” has also become a metonym, used to symbolize much more than a literal street or commercial district. We hear politicians and political pundits proclaim that “we don’t want policies that help Wall Street but hurt Main Street,” opposing the two phrases to represent big business, and ordinary people, respectively. The Collins English Dictionary agrees. Its second definition for Main Street is “ordinary people in general.” The association with small towns is also well established. Sinclair Lewis begins his classic 1920s novel Main Street with this sentence: “This is America – a town of a few thousand, in a region of wheat and corn and dairies and little groves.”

Architects and planners may use “Main Street” to represent a newer walkable commercial strip modeled after the classic Main Streets of towns past.

For sure, though, “Main Street” is an established icon of traditional America, along with the family farm and Thanksgiving turkey dinners. It’s now something that used to be, much more than something that is, and it has become suggestive of values that many continue to hold dear – of community, of a work ethic, of individualism in business, of an environment where crime is rare, to name four.

I just plugged the phrase into Amazon’s search engine and it delivered an astounding 47,279 results. There’s overlap, of course – five of the first six results are different editions of the Sinclair Lewis novel – but you’ll also find several movies, the famous Rolling Stones album some think to be their best (Exile on Main Street) a book on climate change (High Tide on Main Street), an electric guitar, women’s shoes, and a book on how to eat (Main Street Vegan), among many, many other things. Association with Main Street sells, apparently.

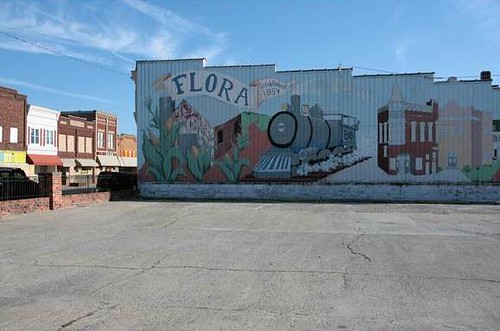

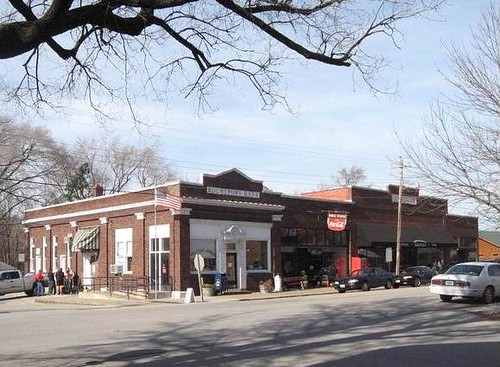

As you can see in these highly evocative photos by Sandy Sorlien, though, a lot of once-thriving, literal Main Streets are now dead or hanging by a thread. In some cases you can say the same about the towns they inhabit, as I wrote in my post, “Are You Ready for the Country?” some time ago, focusing on Fulton, Indiana; Chesnee, South Carolina; and Yreka, California. My collaborator Lee Epstein explored some of the causes and possible remedies last fall.

Even the Main Streets that are relatively healthy today evoke the past, not the present. It's not a coincidence that the best-known program on Main Streets sponsored by an advocacy organization is housed in the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

Sandy Sorlien is a professional photographer, writer and educator who, because of an editorial assignment early in the last decade, became acquainted with the architecture and planning field of new urbanism and was strongly drawn to it because so much of her work had been spent photographing the old urbanism on which the new is based. (The new-mimicking-old meme recurs often in this post.) The key event was her participation in the Mississippi Renewal Forum organized by the Congress for the New Urbanism after Hurricane Katrina in 2005. (I think that may rank as the new urbanists’ finest moment to date. I’m both a longtime CNU member and occasionally a CNU critic, but that particular effort to assist the rebuilding of a devastated region – all volunteered time – was supremely laudable.)

Sandy – we know each other a little, though not really well yet, through mutual friends – “got the bug,” as we used to say when I was growing up. Her own words: “Suddenly I was a full-time code writer and planner, and teacher of coding workshops. This work took me far beyond the Gulf Coast, to at least twenty American cities and five countries.” She was working on a book of Main Street photos when the Katrina work interrupted the book and changed her life. Sandy is still deeply involved in new urbanism, but also returning to the book-in-progress, with the working title The Heart of Town: Main Streets in America. She graciously agreed to allow me to use her photos for this post.

One of the causes of the decline of real Main Streets is that the scale of the retail economy in our country has changed so dramatically since their heyday, with expansionist and successful superstores and national chains leaving little room for small, local businesses to prosper. It also must be said that even small local businesses, if successful, typically want to expand and proliferate – it seems an axiom of capitalism – and the results may be something beyond what the Main Street model can hold. (It’s interesting to consider that perhaps our most iconic manifestation of sprawl, Walmart, once was a local, small business on a Main Street in a small town.)

In a closely related point, Main Streets have also faded because of the proliferation of suburban sprawl, which sapped the life and investment out of traditional community centers, including small downtowns. Ironically, the big indoor shopping malls that dominated American retail – and, to an extent, cultural – life in the 1970s through the 1990s were themselves modeled after authentic Main Streets, but with all the physical environment developed at the same time and all the shops placed in highly controlled indoor environments that one could reach only by driving. Once indoors, though, the shopping and strolling atmosphere was car-free.

In an era when (sadly) many white people were afraid of cities, highly controlled suburban environments became the antidote. When I was in my early teens in a small southern city, you went downtown for shopping and chance encounters with friends; by the time I graduated from law school, people went to the malls. The suburban teens in my extended family still do.

Oddly (from today’s perspective), in the 1970s and 1980s, some cities tried to compete with the suburbs by creating mall-like environments on what used to be their more authentic shopping streets downtown. It didn’t work, and in some cases only accelerated the decline of traditional commercial strips. Today, it is the suburban malls that are on the decline, and some of those disinvested urban districts are revitalizing and reclaiming their urban commercial streets, my favorite example being Crown Square in Old North Saint Louis.

Meanwhile, in the suburbs, some developers have been building “lifestyle centers” outdoors, with actual streets, creating a commercial-district model somewhat closer to authentic Main Streets in design. But, really, it’s just taking the concept of the indoor mall, whose design was partly based on attributes of traditional streets, and removing the enclosure. This, too, is ironic, because the oldest suburban shopping centers (for example, Atlanta’s Lenox Square) were first built outdoors and only later converted into enclosed malls. (Lifestyle centers seemed to be building momentum around the time that the great recession killed just about all suburban development, so I don’t know whether the model has a future or not.)

Some of these new places can be pleasant in their way, but they don’t feel anything like real Main Streets to me. Neither do any others that are part of new developments. They may be something else that’s OK (for instance, the very pleasant and successful Bethesda Row in suburban Maryland), but to me they aren’t Main Streets, no matter what the developers and their designers call them (and no matter whether their designers consider their work progressive or not). I think that’s because true Main Streets grew organically, a shop at a time, each designed by a separate architect and built for a separate owner. The shoe store wasn’t designed and built by the same people at the same time as the restaurant to its left or the hardware store to its right. Each property was individually owned. I’m not sure any one developer or planner can re-create that kind of environment in something totally new.

The places in America that still have successful Main Streets likely have special economic circumstances, such as a tourist economy, a truly remote location, or a surrounding or nearby wealthy suburb whose residents like the historic, walkable atmosphere for certain occasions but go to the mall or a big-box to buy clothing or electronics.

But should we care? A by-the-numbers environmentalist may not have a reason to: if land consumption is reasonably limited by new models, if places are walkable and reduce car trips and emissions by placing shops, services and people close together, if they are well located (and especially if also transit-served), why worry if someone’s sentimental bit of Americana isn’t what it used to be? There’s no need for a horse-and-buggy or an icebox anymore; maybe we no longer need a barbershop next to a children’s clothing store next to an insurance office, either.

That’s true to an extent but, personally, I care about more than the numbers. We do need new places to have the right characteristics, but to me there remains something profoundly lonely in the decline of the old, as Sandy captures so well in her work. There’s also loneliness in dead big boxes and empty malls. But there’s not the same sense of loss.

If you live in or near Philadelphia, you can attend a program later this month featuring Sandy and Temple University professor Miles Orvell, author of The Death and Life of Main Street: Small Towns in American Memory, Space, and Community. The announcement suggests that they will be delving into some of these very questions:

“What is an American Main Street? Is it a memory or image that has been perpetuated through American writing and art? A real space within new urbanist town planning? Or is it a place where some are welcome and others are shunned? Perhaps it is all of the above. Join us to examine these real and imagined notions of American main streets . . .”

For more of Sandy’s great Main Street images, go here. For her blog Street Trip, go here.

(Please note: Sandy Sorlien's photos have full copyright protection except for those from the Transect Collection - noted when you move your cursor over the image - which are licensed for educational use.)

Related posts:

- The fall - and rise - of small downtown America (by Lee Epstein) (September 7, 2012)

- Can we balance the old and new as a place evolves? (December 28, 2011)

- Does the sustainable communities agenda have something to offer rural America? (December 7, 2011)

- The importance of legacy to sustainability (November 28, 2011)

- Are you ready for the country? Rural communities & smart growth (part 1 of 2) (August 3, 2010)

- The revival of Main Streets (July 9, 2010)

Move your cursor over the images for credit information.