Best & worst cities for convenient public parks, and why it matters

Posted June 19, 2013 at 2:00PM

In Minneapolis, the Trust for Public Land (TPL)’s highest-rated big city for public parks, 95 percent of residents (including roughly the same portion of low-income residents) live within a ten-minute walk of a city park. But in Charlotte, the organization’s lowest-rated big city, that number drops to only 26 percent. In Albuquerque, 81 percent of residents live within walking distance of a city park; in San Antonio, only 32 percent do.

These numbers come by way of TPL’s 2012 City Park Facts and its interactive ParkScore index. I’ve been hoping for a while that some organization would perform this kind of analysis, difficult though it must be, because gross numbers of park acreage and park spending don’t really tell us much about how city parks affect people. Even these access numbers don’t get to quality, of course, but it’s a great start. While I love large, signature parks – such as New York’s Central Park, San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park, or Washington’s Rock Creek Park – I love neighborhood parks even more. For me, it’s not about the amount of park land as much as it is about the distribution.

Here are seven cities with especially poor city park access, according to TPL. In each case, over 60 percent of residents do not have walkable access to a city park:

- Charlotte

- Jacksonville

- Louisville

- San Antonio

- Indianapolis

- Fresno

- Nashville

By contrast, here are eight cities with outstanding access to public parks, each with one or more parks within walking distance of 90 percent or more of its residents:

- San Francisco

- Boston

- Washington

- New York

- Minneapolis

- Philadelphia

- Seattle

- Chicago

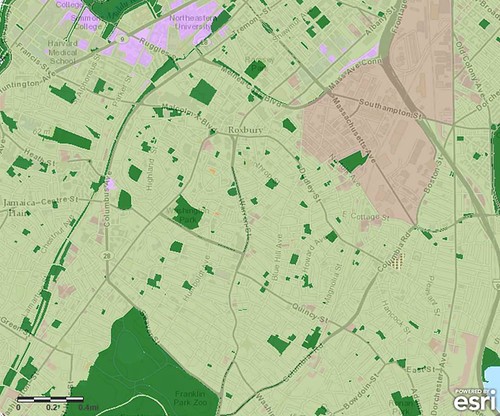

These cities have large parks, but also neighborhood-scaled parks distributed throughout the city, as the accompanying map of parks in Boston demonstrates.

The precise numbers in the two TPL reports differ slightly. ParkScore, for example, looks at the top 50 US cities by population; City Park Facts looks at the top 40. (Minneapolis, TPL’s top-rated city in ParkScore based on a number of factors including, in addition to park access, measures of park size and investment, isn’t rated for park access in City Park Facts.) But the numbers and rankings are generally consistent between the two databases.

As we become more urban as a nation, and many of our neighborhoods and suburbs become denser, access to outdoor facilities and nature becomes more important. Harvard biologist Edward O. Wilson is credited with coining the term biophilia, “the innately emotional affiliation of human beings to other living organisms.” Indeed, for our ancestors a keen awareness of the natural environment was essential to survival. When we are deprived of nature, we lose a basic aspect of humanity.

It is not surprising that all sorts of research backs this up. An academically rigorous review of 86 peer-reviewed studies published since 2000, conducted by Danish researchers for the International Federation of Parks and Recreation Administration, was published in January of this year. It found an immense range of correlations between nature and public health, from reduced headaches to longevity:

“Nature and green spaces contribute directly to public health by reducing stress and mental disorders, increasing the effect of physical activity, reducing health inequalities, and increasing perception of life quality and self-reported general health. Indirect health effects are conveyed by providing arenas and opportunities for physical activity, increasing satisfaction of living environment and social interactions, and by different modes of recreation . . .

“The direct health benefits for which we found evidence on positive effects included psychological wellbeing, reduced obesity, reduced stress, self-perceived health, reduced headache, better mental health, stroke mortality, concentration capacity, quality of life, reduced Attention Disorder Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) –symptoms, reduced cardiovascular symptoms and reduced mortality for respiratory disorders, reduced health complaints, overall mortality, longevity, birth weight and gestational age in low socioeconomic population, post-disaster recovery, and reduced cortisol.” [Citations omitted.]

The evidence for positive impacts of urban parks on physical activity was highlighted as “strong,” with the academically established evidence in support of other effects found to be at least “moderate.” (Conversely, when a correlation between parks and nature was insufficiently established in the literature, as with the effects on lung cancer or diabetes, the authors said so.)

Another large study, reported in a monograph published by the National Recreation and Parks Association in 2010 found a direct correlation between health effects and proximity of parks:

“Scientists in the Netherlands examined the prevalence of anxiety disorders in more than 345,000 residents and found that people who lived in residential areas with the least green spaces had a 44 percent higher rate of physician-diagnosed anxiety disorders than people who lived in the greenest residential areas. The effect was strongest among those most likely to spend their time near home, including children and those with low levels of education and income.

“Time spent in the lushness of green environments also reduces sadness and depression. In the Dutch study, the prevalence of physician-diagnosed depression was 33 percent higher in the residential areas with the fewest green spaces, compared to the neighborhoods with the most.”

The NRPA report even cites studies finding lower levels of aggression, violence and crime in Chicago housing projects with views of vegetation than in those without.

People intuitively appreciate these benefits and, as a result, are willing to pay a significant premium for living near nature. According to a 2006 report published by TPL, a review of 25 studies investigating whether parks and open space contributed to values of neighboring properties found increased value in 20 of the studies. Those benefits accrue to the municipalities as well:

People intuitively appreciate these benefits and, as a result, are willing to pay a significant premium for living near nature. According to a 2006 report published by TPL, a review of 25 studies investigating whether parks and open space contributed to values of neighboring properties found increased value in 20 of the studies. Those benefits accrue to the municipalities as well:

“The higher value of these homes means that their owners pay higher property taxes. In some instances, the additional property taxes are sufficient to pay the annual debt charges on the bonds used to finance the park’s acquisition and development. ‘In these cases, the park is obtained at no long-term cost to the jurisdiction,’ [Texas A&M professor John] Crompton writes.”

The TPL report cites corroborating evidence from the University of Southern California, finding that investment in a pocket park in a dense urban neighborhood would pay for itself in 15 years as a result of increased tax revenues. Indeed, parks can help revitalize distressed neighborhoods.

In short, intuition supports city parks and so does evidence.

I sometimes get weary of city or state rankings, which can be sort of gimmicky. Close scrutiny can almost always find details in the data that call some of the comparisons into question. But, in the case of TPL’s study of park proximity, the difference between, say, Louisville (32 percent of residents within walking distance of a city park) and Boston (97 percent of residents within walking distance of a city park) is immense. Adjust the numbers up or down and we’re still talking about one city with much better access to parks than another. If rankings get people talking about the issue, and park proximity becomes a stronger factor in planning and investment, that’s a good thing.

Related posts:

- Nashville's new hypergreen riverfront park (April 27, 2012)

- Turning abandoned and obsolete properties into "park-oriented development" (April 20, 2012)

- 5 graphs and 4 photos tell the story on obesity, diabetes & walking (March 28, 2012)

- The good news: we're getting more city parks. The bad news: we have less money to take care of them. (December 13, 2011)

- How pocket parks may make cities safer, more healthy (November 23, 2011)

- Parks for people, and people for parks (April 28, 2011)

- How parks can help revitalize distressed neighborhoods (March 16, 2011)

- Interested in how to think about city parks? Get this book (May 7, 2010)

- Using urban density to support parks, and vice versa (March 9, 2010)

Move your cursor over the images for credit information.

Please also visit NRDC’s sustainable communities video channels.