Traditional downtowns reconsidered: some further thoughts

Posted January 2, 2014 at 1:28PM

On December 18, at the height of the holiday shopping season, I published an article titled, “Is the ‘traditional’ downtown a thing of the past? Is that OK?” (Editors used different titles in publications other than the original on NRDC’s Switchboard site.) I meant something nuanced by that article, and I meant the title as two open questions about which I felt a little uncertain. But I'm not sure the nuances came across, given some headlines and tweets that suggested I was pronouncing downtowns "dead," a word I never used in my article. (Other than on my home site, I don't write or approve the headlines.) Yikes; that isn't what I meant.

In any case, my writing clearly struck a sensitive nerve among many readers – or readers of tweets, or headlines, at least. Many people took the article to mean that I don’t believe in the inner-city revival that is taking place in so many American cities, and their central commercial districts, and some commenters – particularly committed urbanists – disagreed with that notion. (So do I.) My friend Lloyd Alter over at Treehugger even went so far as to publish a rebuttal, supported by a sharply worded tweet to the effect of, "Kaid thinks traditional downtowns are dead. I don't."

In all, I received a lot of good, insightful comments that enriched my own perspective and I hope enriched those of readers. This has prompted a lot of reconsideration on my part. I actually don’t disagree with most of the responses, which makes me think I may not have expressed myself well enough in that original article. So, today I am revisiting the topic with some further points that I hope will clarify things at least a little:

Inner and central cities are coming back

If there is anything I don’t want to be misunderstood about, it’s my conviction that central and inner cities are making a pronounced and very exciting comeback in much of America. The severe and tragic disinvestment that crippled so many American cities in the second half of the 20th century has bottomed out and, in most places, begun to reverse. Central cities are now growing faster than suburbs. In Washington, where I live, the population of the District of Columbia proper – “the city” – in 2012 was 632,323, up ten percent since 2000. Housing prices are also recovering faster in centrally located and transit-served locations.

This is good news not just for the viability of walkable urbanism but also for the environment. Centrally located neighborhoods generate substantially less driving and related emissions than do outer locations, due both to fewer vehicle trips per person and to shorter driving distances, on average. Demographic forces and a growing preference for urban lifestyles suggest that inner citiies will only strengthen over time. I’m pretty much devoting my career to strengthening these trends.

But let’s be honest: it’s still a work in progress in many places

The degree to which inner and central cities have come back, however, varies greatly from one metro area to another; in most eastern and midwestern cities the revival remains incomplete notwithstanding the hopeful direction.

The population living within the city limits of Atlanta, for example, remains 13 percent below its peak in 1970. Over twelve times as many people live in Atlanta’s suburbs as live in the city itself. In Washington, DC, where the urban recovery has been considered strong, the central city population remains 21 percent below its peak some sixty years ago. In St. Louis, where the recovery has been weak, the central city population is only about a third of what it was in 1950. Philadelphia, Milwaukee, and Birmingham are three more cities that have yet to regain their peak populations.

Western cities have fared better. By contrast, San Francisco and Seattle both now enjoy the largest central-city populations in their histories. Both cities lost population between 1960 and 1980, but not as much as other cities. (I suspect that, sadly, one reason may be greater racial homogeneity.) They both had fully recovered by 2000 and have continued to grow since. Boise, described so well by Elaine Clegg in her comment on my original article, also has grown steadily in recent years and suffered no population loss at all during the period when other cities were being disinvested.

As a result of this wide variation among cities, our perception of how strong the recovery is, and how optimistic we feel about it, may depend on where we live. And, overall, we can’t forget the sobering finding that, in a 2013 national poll trumpeted by some as a boon for smart growth, a full 52 percent of respondents said they prefer to live in a single-family, detached home with a large yard, as opposed to 24 percent who prefer the same type of home with a small yard. Only 14 percent said they prefer an apartment or condominium.

What’s a ‘downtown,’ anyway, and what do I mean by ‘traditional’?

I think some of the dissonance between my intentions and the perceptions of some commenters may have something to do with semantics. I should have defined “downtown” in my original article, so we were all talking about the same thing, at least.

I was referring to what used to be called the “central business district,” or CBD. But, in Charlotte, that’s “Uptown.” In New York, it may be “Midtown,” though New York is kind of a world of its own when it comes to generalizing about cities. (In New York, “downtown” means lower Manhattan.) On Twitter, one of the commenters on my article pointed out that Midtown Atlanta is booming. So it is, and that’s a very good thing. But to me, psychologically, Midtown Atlanta is Midtown, about a mile north of and separated by a freeway from downtown.

Heck, in the DC area, many people from the suburbs say that my wife and I live “downtown” simply because we live in the city. But, although we are extremely fortunate to live in a walkable, historic residential neighborhood with a moderate amount of commercial activity two to three blocks away, it’s still a few Metro stops away from what I consider to be downtown.

Geography may not be the main point, anyway. I think my main point had to do with the “traditional” part. Back in the day, downtown was the central area where people went to do stuff – to work in big offices, to do holiday shopping, to attend the ballet or symphony, to go to an impress-your-date restaurant. When I suggested that today’s downtown recovery seemed less than complete, I think commenter Alex B. gave a great response:

“I would challenge the idea that what a successful downtown like DC is trending towards is somehow less complete (in your words); what a downtown like DC is building towards is quite complete . . . Instead, I think you're describing primacy. And no, the downtown of today, even a successful one, will never have the primacy over all other nodes in a region the way that pre-war downtowns dominated their regions.”

When I awkwardly described today’s urban experience as more “diffuse” and less geographically centered, it was that loss of primacy that I was really referring to.

There’s a much more positive way to put that, of course, and some commenters did. Payton Chung opined that historically cities were typically polycentric, and that today’s cities are returning to “a much stronger sectoral orientation.” John Bailey articulated the pleasures of conducting one’s activities not in a downtown but in a “neighborhood”:

“I have been lucky enough to live in a couple of great cities (San Francisco and DC), but even those (non-cratered) downtowns never did anything for me. I find urban neighborhoods infinitely more interesting, and even more urban, than downtowns . . .For me, and I know this is completely subjective, the things that are great about cities (lively gathering spots, different building types, small stores, pocket parks, diverse neighborhoods) have always existed in the neighborhoods than the downtowns.”

I think those are great points. If the CBD is weaker as a place of primacy in some cities than it once was, the neighborhoods may remain strong and interesting. I know I almost always patronize neighborhood restaurants now rather than downtown ones. The trips from home are shorter and sometimes can be made on foot; the food and experience remain fantastic. I’ll always patronize neighborhood retail, too, where it exists and provides what I need – though, in my case, for some items I’ll have to venture somewhere else.

What’s emerging in downtowns today is pretty darn exciting

While I may lament some things about old-fashioned, everybody-went-there downtowns that some of us baby boomers experienced in eastern and midwestern cities – such as having five or six large department stores, along with scores of smaller shops, to choose from in DC, all within walking distance of each other, and a sense of excitement about centralized, critical mass of place – I like what I see happening in many downtowns today.

DC and Atlanta have subways that we now take for granted, for example, but didn’t exist when I first lived in either city. Both of those cities are getting streetcars, too, as is (finally!) Cincinnati. This is good stuff. The commenters who took me on completely missed this passage from my original article:

“I pretty much love what is happening in central Washington today – including, by the way, our outdoor holiday market. Downtown DC has become an exciting place again, to work, to eat, to gather, to shop.”

What I find most exciting of all is a boom in downtown housing, which I see prominently in Washington and even when I visit my hometown of Asheville. Putting people within walking distance of what downtown has to offer – both now and potentially – is immensely helpful to downtown’s viability and all the environmental benefits that come with it. And it makes downtowns more, not less, complete. I should have acknowledged that in my original article.

Darin Givens, who writes the blog ATL Urbanist, expressed the concept of a living downtown well in a comment on my article:

“I live in Downtown with my wife and kid in a great old 1913 office building that was converted to condos. We've got awesome neighbors here and in other nearby condo and apartment buildings, we've got GSU's campus all around us bustling with activity. It's wonderful . . .This situation with people living here and investing in the place in the way that only residents can -- alongside store owners, students, office workers and events attendees -- that's the most exciting kind of downtown I can think of.”

To be honest, I couldn’t agree more.

What saddened me about a recent visit to downtown Atlanta, though, was also real. Peachtree Center and Peachtree Street running south from there, so lively in my college days, were virtually deserted on a weekday afternoon in the fall. The area had a windswept feeling to it, as did Centennial Olympic Park, about which I had heard such great things. I’ll grant that it’s possible I caught these places on an atypical day, but I wish I could show Darin what downtown Atlanta was like when I lived there and he could show me what he likes about downtown now. I suspect we’d both learn a lot, and have a good time, too. (For the record, I had much more positive experiences on that trip in some other Atlanta urban neighborhoods.)

So why the generational difference of opinion?

By citing with approval Aaron Renn’s observation that baby boomers view downtowns differently from younger generations, I certainly didn’t mean to incite any kind of inter-generational verbal warfare. Some of the comments, both on the article and on Twitter, though, suggested that a few people were ready to engage if I were. One commenter made it clear he wanted no part of the kind of centralized, but car-dependent downtown shopping experience that baby boomers once enjoyed. (For what it's worth, there probably was less residential walkability downtown in the 1960s but transit ridership nationally claimed a greater mode share then than now.) Someone commenting under the name “alurin” (?) wrote, “But isn't it the Boomers themselves who helped to destroy the old downtowns, by moving out to the suburbs and shopping at the malls?”

As for the responsibility of the boomers, yes and no. By the time most boomers came of age, in the 1970s and 1980s, their parents had already moved to the suburbs. The first and second wave of regional malls had already been built, too. It’s true that most of my generation (like most Americans of all ages until quite recently) stayed there and disdained downtowns, though. We boomers certainly had a role in the problem. (For the record, I personally have never lived in a suburb at any point in my life, but I don't claim to be typical.)

Here’s what I think it comes down to: In a lot of cities, downtowns are recovering, and that’s exciting, but many aren’t yet fully recovered (and some, particularly in the Rust Belt, have a long way to go). Even far outside the Rust Belt, the small city of Lynchburg, Virginia, which I visitsed a couple of years ago, has some exciting plans underway; but its main street also has historic architecture with many boarded up buildings, some deteriorating badly, and little foot traffic.

The degree to which the incomplete recovery affects your view may well be, to an extent, age-dependent. If you came of age in, say, the 1990s or 2000s, the damage had already been done. Your experience has been primarily shaped by what has come since, including all the good things going on now. It has pretty much been a positive trajectory (but for a few particularly downmarket places, and even they are showing innovation and potential) that you have witnessed and helped shape.

But, if you’re (cough) older, you also witnessed it all falling apart. The reasons included not only a desire on the part of homebuyers for large yards and privacy but also some darker ones – crime and its fear especially, but also poverty, and “white flight.” Three main corridors in DC burned to the ground in riots the year before I arrived. I have to include the very important issue of perceived public school deterioration in the calculus, too. Even today, I know people who start out living in the inner city and, all things being equal, would prefer to stay there; but, instead, they move farther out when their kids reach school age rather than trust inner city schools to educate them. I'm saddened by that but I also understand it.

Those of us who love cities – and I wear the label with honor – are truly energized by the comeback from the fall. But boomers' original point of comparison was a very robust (and maybe falsely innocent) time for downtowns and inner cities. Today, we’re greedy, and we want it all – today’s transit improvements, today’s creative energy, and especially today’s emerging walkability, but coupled with the robust commercial, retail and entertainment scenes of back in the day. And, sure, we want it in the neighborhoods too. We see lots of progress but not (yet) the full package in many cities.

Too much to ask? Maybe. But wishing for the past is always a losing proposition; perhaps it's time to let the old vision go and wish for something more of this century.

Perhaps something different, but moving in a good direction

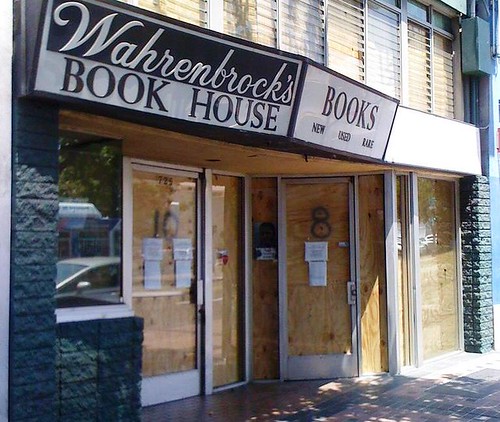

I do have a feeling that the re-emerged downtowns of the twenty-first century will be at least somewhat different from what I called the “traditional” ones of the past. Bricks-and-mortar retail has changed tremendously from pre-internet days, for example, and from times when there were fewer national and international chains. I’m not enough of a prophet to foresee exactly how it will look and feel in the coming decades, but the retail of the future will be different than it was back in the day.

It already is. How many music stores have you seen recently? Bookstores? We may never have five or six large department stores in downtown DC again.

I’m not saying these retail differences are all bad – downloading music is awfully convenient, for example, and so is internet shopping – though I do miss multiple, well-stocked, independent bookstores in every city. The nature of office work is different, too, with telework gaining popularity and office space per worker shrinking. Finally, our metro regions, for better or worse, are far more geographically vast than they once were. All these things work against some of the ways downtowns used to function.

But having more housing downtown is not a bad tradeoff, especially given that (as some commenters correctly pointed out) housing tends to attract more retail. While I may harbor some doubts that downtowns will come back as they once were, I want to be clear that I do not mean to say that what is going on now is leading toward something "worse." I certainly don't mean to argue that what is happening in downtowns today is insignificant, or irrelevant.

Quite the contrary: it is an immensely exciting time for cities and their downtowns. I want us all to work together on making twenty-first century downtowns as good as they can be.

Most of all, I think we can all agree that cities are highly complex organisms, experienced differently according to who and where we are. None of us knows all the right answers, and those who say otherwise are fools or pretenders, in my humble opinion. As I tweeted to my friend Lloyd, I want the forums for which I write to be places where we can exchange perspectives and learn from each other. I certainly meant what I wrote in that original article, but it didn't express the totality of how I feel about cities and downtowns. I'm glad some commenters pushed me to think some more about it, and I hope my thoughts have done the same for others.

All that said, this is my first article of 2014. Thanks so much for reading, and here’s wishing everyone a magnificent new year!

Move your cursor over the images for credit information.