Promoting people-oriented development around transit

Posted May 21, 2012 at 1:36PM

Two years ago, I wrote a short article titled Transit-oriented development requires more than transit and development. My point was that, to maximize the powerful potential of public transportation to reduce automobile dependence and associated environmental impacts, we should be thoughtful about it. Orienting development to transit requires more than just placing development near transit.

For example, the densest residential and commercial buildings should be placed closest to the station. Retail uses should be conveniently accessible. Walking routes should be clear and multi-modal transfers and vehicle drop-offs should be facilitated. And so on. I offered some sources of information on station-area planning that shed some light on the issue.

I didn’t answer the all-too-obvious question of what sort of legal and policy underpinning was required to get us to the desired result. But yesterday, while browsing the new website of an architecture and planning firm I know professionally (Moule & Polyzoides designed NRDC’s Santa Monica office), I ran across a very insightful essay written by one of the firm’s principals, Stefanos Polyzoides, and addressing just that issue.

The article makes the very good point that transit-oriented urbanism works best when it is fine-grained, consisting of many different types and scales of development, created incrementally over time by different developers with varying circumstances and objectives. (My friend Liz Dunn is also very articulate on this point.) Larger "mega-projects," though they have a place, simply don’t create the same feel of being in a real city, with the kind of diversity that those of us who love cities find so appealing. But fine-grained variety can hardly be mandated. So how do we create a framework that encourages and facilitates it?

The article makes the very good point that transit-oriented urbanism works best when it is fine-grained, consisting of many different types and scales of development, created incrementally over time by different developers with varying circumstances and objectives. (My friend Liz Dunn is also very articulate on this point.) Larger "mega-projects," though they have a place, simply don’t create the same feel of being in a real city, with the kind of diversity that those of us who love cities find so appealing. But fine-grained variety can hardly be mandated. So how do we create a framework that encourages and facilitates it?

One answer may be a form-based zoning code. As some readers may know, traditional “Euclidean” zoning emphasizes permissible land uses in a given location while giving less attention to the scale and form of buildings and how they relate to the street and each other. Form-based codes do the opposite. Polyzoides believes that they are ideally suited to the task of creating transit-oriented development:

“Transit-oriented development master plans typically establish the vision for such transit-centered neighborhoods, districts and corridors. They are best implemented through the actions of many developers, their projects often including many and diverse buildings and public spaces . . .

“Form-based codes are the indispensable tool for seeding the alternative to mega projects: incrementally assembled ensembles of smaller buildings and the human scaled places between them. This method of coding offers predictability by establishing the building, open space, landscape, and right of way standards that deliver an orderly urban form, by many development interests, over time.

They also regulate uses in a flexible manner that allows a fast response to changing economic patterns and space needs. As form-based codes support phased, incremental design actions, they become ultimately supportive of both private and community interests. They maximize the performance of private projects, while building up a stable and permanent public realm.”

The extended essay also emphasizes that there is a difference between emphasizing a certain architectural style, which Polyzoides does not advocate, and setting the bounds for urban form, which is more about articulating space in a way that facilitates walking and makes best use of the presence of transit. The essay also addresses such related issues as density, transit routing, public collaboration, architectural detail, and more.

Detail-oriented readers looking for an example might want to visit the Station Area Form-Based Code for Farmers Branch, Texas, a suburb north of Dallas. According to the Form-Based Code Institute, the district is located within a struggling commercial district anticipating redevelopment in conjunction with extension of a Dallas Area Rapid Transit (DART) light rail line to the city. Farmers Branch initiated a visioning process in 2001 that has now resulted in both a citizen-endorsed master plan and the new code, “designed to foster a vibrant town center for Farmers Branch through a lively mix of uses—with shop fronts, sidewalk cafes, and other commercial uses at street level, overlooked by canopy shade trees, upper story residences and offices.”

The introduction to the code for Farmers Branch offers a concise framing of the concept:

“The Station Area Form-Based Code is a legal document that regulates land development by setting careful and coherent controls on building form—while employing more flexible parameters relative to building use and density. This greater emphasis on physical form is intended to produce safe, attractive and enjoyable public spaces (good streets, neighborhoods and parks) complemented with a healthy mix of uses. With proper urban form, a greater integration of building uses is natural and comfortable. The Form-Based Code uses simple and clear graphic prescriptions and parameters for height, siting, and building elements to address the basic necessities for forming good public space.”

The document demonstrates that, while form-based zoning codes can be every bit as precise and demanding as use-based codes, the emphasis on good public space is very different. The city’s website does not credit an architecture and planning firm with support on the project, but someone did a lot of work.

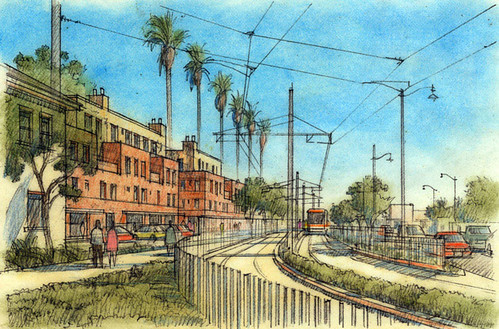

There are also a number of nice-looking transit-area plans and codes on the Moule & Polyzoides website, which contains a lot of good information on other urbanism and sustainability topics as well. (All of the images accompanying this post are from M&P, which kindly granted me permission to reproduce them. Click on them for the specifics.)

Related posts:

- Impressive Denver study on equity & transit should become national model (May 4, 2012)

- New data show how transit corridors reduce traffic, increase walking (August 17, 2011)

- Households in transit-oriented locations save more energy and emissions than even 'green' households in sprawl (February 24, 2011)

- The remarkable story of Oakland's Fruitvale Transit Village (part 1) (February 17, 2011)

- The importance of transit context and design (September 27, 2010)

- New mapping vividly illustrates the effect of transit on automobile dependence (June 12, 2009)

Move your cursor over the images for credit information.