The Plumbers' Law, or how sustainable development helps watersheds (by Lee Epstein)

Posted June 11, 2012 at 1:32PM

Later this week I will be participating in the fourth annual Sustainable Raritan River conference, and speaking about the importance of smart, green communities to watershed protection. It seems a great time to revisit that topic here, with another post guest-authored by my friend and frequent collaborator, Lee Epstein. Lee is an attorney and land use planner working for sustainability in the mid-Atlantic region.

In my day job, I work for an NGO that’s all about water. Being a sophisticated organization, we know that means being all about watersheds. Watersheds are topographic areas where all the rain that falls eventually ends up in a namesake steam, river, lake, or estuary. Thus, for example, the watershed for the Ohio River extends to the towns not only along its banks, but also along its feeder streams sometimes hundreds of miles from the main stem – the Allegheny and Monongahela, coming together at Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; the Kanawha River, whose mouth is at Point Pleasant, West Virginia; the Little Sandy, ending its journey in Greenup, Kentucky; and countless hundreds more streams and places, large and small.

The Plumbers’ Law

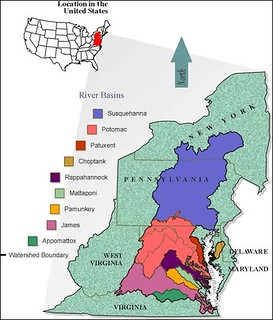

Some watersheds, or sub-watersheds of a little creek, are small – a few hundred acres or a half-dozen square miles; some are incredibly large. In fact, the interesting thing about watersheds is they are “nested,” or interconnected to ever-larger watersheds (the watershed of the Chesapeake Bay covers 64,000 square miles of mountain, piedmont, and coastal plain in six states and the District of Columbia, but within it are also the great Potomac and Susquehanna River watersheds, and thousands of smaller river and stream watersheds).  What that interconnection means is that the “plumbers’ law” rules: waste (not the word most plumbers use!) flows downstream. What happens on the land, what happens in the hundreds or sometimes thousands of cities and towns and counties across a watershed, and to sometimes hundreds or thousands of streams, affects the water downstream. And therein lay the connections with sustainable development.

What that interconnection means is that the “plumbers’ law” rules: waste (not the word most plumbers use!) flows downstream. What happens on the land, what happens in the hundreds or sometimes thousands of cities and towns and counties across a watershed, and to sometimes hundreds or thousands of streams, affects the water downstream. And therein lay the connections with sustainable development.

Sustainable growth “inside” vs. sprawl “outside”

As this blog has covered over the years, sustainable, smart growth and development is necessarily about location, form and function. Becoming greener doesn’t just mean a municipality’s adding a pleasant new park here and there, or planting more trees, although both components may be useful parts of a larger effort. How a town is designed and developed is related to how well it functions, how well it functions is related to how sustainable it really is, and how sustainable it is, is directly related to how it affects its local waters and those who use those same waters downstream.

Compact, mixed-use, well-designed in-town growth can take some of the pressure off of its opposite on the outskirts – or beyond the outskirts – of towns and cities. We know that sprawling growth is generally pretty bad for maintaining environmental quality in a region (air pollution from cars that become necessary in such circumstances, displacement of open land, water pollution from new roads and shopping centers that are begot by such growth patterns).

Getting neighborhood design right means creating safe and walkable streets, which make access and movement easy and pleasant. It means providing for different densities and price points for housing, and creating close commercial destinations that supply daily needs. And it means the thorough integration of green-space that serves a variety of purposes (active and passive parks and greenways, street greenery, vegetated buffers along streams, and stormwater management on parking lots, rooftops, in lawns and gardens and storefronts, and along streets). All of these disparate objectives together unite town form with function. In this way, the things that make cities and towns better places in which to live and work are, it turns out, also pretty good for local waterways and their larger watersheds.

Getting neighborhood design right means creating safe and walkable streets, which make access and movement easy and pleasant. It means providing for different densities and price points for housing, and creating close commercial destinations that supply daily needs. And it means the thorough integration of green-space that serves a variety of purposes (active and passive parks and greenways, street greenery, vegetated buffers along streams, and stormwater management on parking lots, rooftops, in lawns and gardens and storefronts, and along streets). All of these disparate objectives together unite town form with function. In this way, the things that make cities and towns better places in which to live and work are, it turns out, also pretty good for local waterways and their larger watersheds.

Growth is (mostly) a zero sum game

Here’s one reason: in most regions around the country, growth is a zero-sum game (I’ll get to the exceptions in a minute). That means that there’s really only so much demand for new housing, and there are only so many retail dollars to go around, in a region, and once those demands are filled, they’re filled, at least for some period of time. If the demand is adequately satisfied in villages, towns, cities and urban places in the region where people want to live and work, there is no need (and much less likelihood, given the nature of regional economics) for the growth to occur on nearby or far-flung working lands (farms and forests) or across streams and wetlands.

The in-town growth, if accomplished along the sustainable lines mentioned above, does several things, then: it accommodates growth needs in a way that strengthens the region’s towns and cities, and helps keep them – or make them – into places in which people want to be because they grow to love these places with their beauty and functionality; it helps slow or even stop sprawl on the fringe, thus protecting open lands and streams farther up the watershed; and in accomplishing these two things, it helps maintain water quality downstream and elsewhere around the watershed.

The in-town growth, if accomplished along the sustainable lines mentioned above, does several things, then: it accommodates growth needs in a way that strengthens the region’s towns and cities, and helps keep them – or make them – into places in which people want to be because they grow to love these places with their beauty and functionality; it helps slow or even stop sprawl on the fringe, thus protecting open lands and streams farther up the watershed; and in accomplishing these two things, it helps maintain water quality downstream and elsewhere around the watershed.

The zero-sum equation doesn’t always hold, of course. There are some metropolitan regions, for example, that for whatever reason exhibit hyper-markets (the Washington, DC area is one, New York, for its magnitude if nothing else, is another, the San Francisco-Oakland region is a third). In these places, it almost doesn’t matter if hundreds of thousands of square feet of commercial space or thousands of housing units are absorbed annually in the urban centers – unchecked, sprawl will also continue at the fringe. These places still deserve high quality, sustainably-designed, urban development and redevelopment in their core towns, from which their associated waterways – and larger watersheds -- can significantly benefit. It’s just that in these places, “good growth” inside doesn’t automatically reduce the “bad growth” outside, absent strong rules and local government policies that can help accomplish those ends.

Sustainable development helps support healthy watersheds

This brings us back to where we started. Of course, obtaining sustainable development in town isn’t enough, in and of itself, to guarantee high quality, fishable and swimmable rivers and streams.  Industry plays a part; utilities and wastewater treatment plants play a part; sensitive farming, ranching, and/or timbering play a part, all in different proportions depending upon the particular watershed in question.

Industry plays a part; utilities and wastewater treatment plants play a part; sensitive farming, ranching, and/or timbering play a part, all in different proportions depending upon the particular watershed in question.

There is, nevertheless, a direct line to be drawn between ecologically healthy watersheds with good water quality in both local and more remote rivers and streams, and sustainable development across a watershed’s towns and cities. One reason is because, quite simply, this is how watersheds work.

The other reason is because, quite simply, this is how sustainable development works.

Additional posts by or with Lee Epstein:

- Citizen participation in the design of sustainable communities (May 16, 2012)

- Will the real green colleges please stand up? (by Lee Epstein) (March 21, 2012)

- Coming to America: immigration and sustainable communities (May 9, 2011)

- Warning: black helicopters on the horizon (or so they say) (March 23, 2011)

- The messy issue of design in smart growth (January 6, 2011)

- Musings on vacation sites, consumption, and resilient communities (July 16, 2010)

Move your cursor over the images for credit information.