Can this dead suburban mall be transformed into something better? It's complicated.

Posted June 13, 2011 at 1:27PM

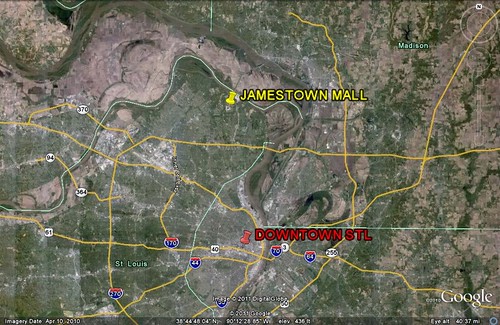

Jamestown Mall, 16 miles north of downtown St. Louis, Missouri, is an environmental disaster. Built on farmland in an area rich with environmentally sensitive fields and floodplains, and completely automobile-dependent, it was built in 1973 – the heyday of shopping-mall speculation – as leapfrog sprawl, in anticipation of more leapfrog sprawl to come around it. Designed to house 1.2 million square feet of retail spce, it borders farms and sensitive land to this day. It never should have been built. But that was a time when most of us didn’t know any better, and suburban expansion was actually thought to be exciting.

The mall has also been pretty much of a disaster economically. The region didn’t grow in a way to support a large shopping center in that part of St. Louis County. Restrictions eventually and rightfully imposed because of issues related to fragile karst topography and potential flooding prevented some nearby development, depriving the mall of potential customers. The Missouri River just to the north of the site created an access barrier, and a competing mall opened up on the other side. As a result, today the vast impervious parking lots of Jamestown Mall sit mostly empty, the stores inside either abandoned by retailers or greeting few customers. What housing there is nearby is scattered and decidedly low-density.

So, what now? I can make a case that the land should be reverted to agriculture, which it should have remained all along. That would, however, be extremely difficult to accomplish financially and make a waste of the materials and resources that went into building the site.

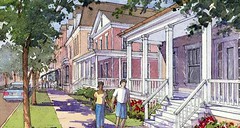

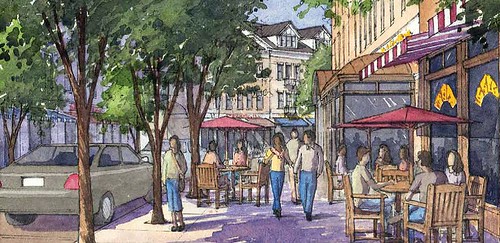

So the municipality, with the assistance of Dover, Kohl & Partners (who also did the fabulous planning for El Paso, Texas that I described a while back), is considering alternatives for rebuilding the 142-acre site with low-key, walkable, mixed-use development. Architect and planner (and friend) Victor Dover calls it “arguably the most challenging case of retrofitting suburbia we've tackled to date.”

It will be complicated, to be sure, in part because the property is not under single ownership. Instead, its five separate proprietors are likely to make separate decisions regarding parcel use, potential sale, and timing. (Three of the mall’s anchor tenants, JC Penney Outlet, Macy's, and Sears, each own their building along with portions of the parking lot. Two investment entities split the rest. The Sears building is vacant.)

As a result, any master plan must be based on an array of contingencies. It also must be based on an incremental approach, since under any likely economic scenario change will come slowly. Victor says 15 to 20 years, even under optimistic circumstances. There are also the usual zoning complications and necessary approvals, since old contemplated uses will be replaced with new ones.

In a draft plan and accompanying analysis presented to the county last month, Dover, Kohl is recommending that the site’s redevelopment be based on several “first principles”:

Economic principles:

- "Reset" the property in everyone's mind

- Balance private & public interests

- Keep it phase-able to keep it feasible

- Balance neighborhood desires & developer priorities

Placemaking principles:

- Seek to establish a new "heart of the community"

- Design mixed-use, walkable, smart growth

- Emphasize the strengths of the site

- Build for the coming era, not the last one

- Build well, or do not build

The tone of the new plan, constructed with substantial public input, is forward-looking, but also cautious and restrained:

“As evident by the closing of national retailers at the Jamestown Mall site, this location is not well suited for a regional retail center. However, as demonstrated by analysis in the Jamestown Mall Area Plan report, in the format of a village center there is a potential current market for 76,000 to 200,000 square feet of new retail on the site serving the local economy.

“The size of the site, approximately 142 acres, could allow up to 1,400 new single-family attached and detached dwellings and apartments units in addition to the 200,000 square feet of retail, and 80,000 square feet of offices or varying combination of the above.

“The analysis also identifies a potential market for senior living in small lot houses and townhomes which could account for 600 of the new households. The importance of this residential and employment base is essential to make the retail component more attractive to retail developers, investors and successful as a business location.

“At the lower range, the site could support 700 new units . . .”

The ownership parcels are awkwardly shaped, with some of them being discontiguous, as shown above on the color-coded parcel map. The site is roughly the same size as the entire French Quarter in New Orleans.

Dover, Kohl created alternative conceptual plans to allow for one-at-a-time parcel development. For example, compare the four site-planning scenarios below, which differ according to differing potential ownership decisions and economic scenarios. The plan shown at top left is the most ambitious; the one at top right contains much less commercial development; the bottom two concentrate all new buildings in the northwest corner of the site:

The plan’s best illustration of what is possible is based on transformation of the Sears property on the northwest portion of the site. Here’s the before and after:

The 141-page document contains much, much more information on land use and design alternatives, along with extensive environmental, transportation, walkability, and economic analysis (including such detail as recreational facilities, a farmers’ market, and parking strategy). The recommendations appear well-grounded, if inherently uncertain.

If the county proceeds, next steps will include formally adopting the plan; developing and implementing a property acquisition strategy; creating a public-private partnership to oversee development; revising zoning (the plan anticipates adoption of a form-based code); and developing and implementing marketing and economic strategies.

As well thought as this project is, I must confess to a little ambivalence about it. If this were a proposal for greenfield development, I would oppose it. Especially considering the amount of underutilized land in the central city of St. Louis, encouraging the development of 700-1400 new homes way out on the fringe of the region is questionable at best. Environmental problems associated with sprawl aside, market trends away from suburbia and toward city living make it economically risky as well (which may be why it’s a good idea to create much of the project around senior housing rather than attempting to market to millennials). If the redevelopment succeeds, there is also the risk that it will draw further development around it, with the additional development much less likely to be this well-planned.

But the site is decidedly not a greenfield. It’s a current disaster that has the chance to be made into something better, if still far from ideally situated. And, if things work out as hoped, the project may provide a new template for retrofitting a common type of sprawl in challenging and uncertain circumstances.

In a story written by Kelsey Volkman in the St. Louis Business Journal, Victor Dover sums it up: "There is a national need for redeveloping derelict malls. They had 20 or 30 reasonably good years, but the mall era is kind of over."

Here’s a short news feature on the project that ran on local TV. The visuals of the current site are bleak:

Move your cursor over the images for credit information.