For walkable cities, it's not about the density - it's about finding the right kind of density

Posted March 4, 2013 at 12:50PM

A few days ago, I was reviewing some good work by colleagues describing NRDC’s advocacy for sustainable cities. The original draft stressed that dense living is the way to go. Wherever the word "dense" appeared, I crossed it out and substituted the word “walkable.” Not only is “walkable” a much friendlier word; it also captures so many more of the things we need to make the places where we live and work more sustainable and livable.

Consider: Los Angeles is one of the densest cities in America; the godawful tangle of sprawl that is Tysons Corner - the prototypical “edge city” in suburban Virginia - is reportedly denser than downtown Richmond; the horrors of Cabrini Green in Chicago and other decrepit tenement towers were plenty dense. We need density for sustainability, yes, but it needn't be uniformly high density, and if it isn’t people-friendly (and I’ll get into that), we will make things worse, not better.

Even “walkable” doesn’t get us all the way there, because we also need city neighborhoods with nature, culture, good schools, green technology and green infrastructure. I’m not sure I have a single word that captures the whole gestalt. But “walkable” gets us closer than "dense" to describing a sustainable city.

Made for walking

I engage in this bit of word-parsing because I just finished a very good – no, make that fantastic – book by Julie Campoli called Made for Walking, published by the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. I don’t know if Campoli would agree, but I think she started out to write a book about city density (kind of a sequel to 2007's Visualizing Density, which she co-authored with aerial photographer Alex MacLean) and ended up writing something much better than that. Made for Walking isn’t so much about urban density as about the other things that we need in city neighborhoods - in addition to a level of density - to make city living attractive and sustainable.

Let me say early in this article that the hundreds of photographs, diagrams and illustrations she provides in the book to support these points are incredible. Campoli is an immensely talented photographer and graphic artist, and all the images are hers. I would buy the book for the photos alone; it’s the best-illustrated book on neighborhood-scale urbanism that I have ever seen. (Most of the photos accompanying this article are from the book and they are used with permission, ©2012 Julie Campoli.)

Campoli summarizes her key ingredients of city sustainability, which I might describe as “urbanism-plus”:

“The structural elements illustrated throughout Made for Walking – streets, blocks, sidewalks, and connected open spaces together with the intricate mixing of uses – make walking and biking convenient and enable mobility with a vastly reduced carbon impact. These qualities, combined with a comfortable streetscape, create the type of pedestrian-oriented environment that lures people out of their cars. A few other physical qualities may not contribute directly to lowering a place’s carbon footprint but are also essential ingredients in a successful urban neighborhood. These elements, which can be designed in a place to add value, include the things all of us need in varying degrees – greenery, privacy, variety, and a sense of spaciousness.”

Note especially the last sentence. These are the things that make the urbanism succeed. I couldn’t agree more, though I would add green infrastructure and technology to the menu (and so does Campoli, in a different part of the book). I’ve been arguing for a long time now that smart growth and urbanist advocates must become more holistic in our thinking if we are to be true to our values.

Note especially the last sentence. These are the things that make the urbanism succeed. I couldn’t agree more, though I would add green infrastructure and technology to the menu (and so does Campoli, in a different part of the book). I’ve been arguing for a long time now that smart growth and urbanist advocates must become more holistic in our thinking if we are to be true to our values.

A different kind of book

Although the titles are similar, and both share a common underlying philosophy, Made for Walking is a very different book than Jeff Speck’s Walkable City, which came out around the same time and which I summarized in a previous article. Jeff’s book is more of a manifesto, and a very good one, especially about how we need to reduce the influence of cars on cities. It is pure advocacy, using strong language; it contains not a single visual image, and really not that much about design, even though Jeff is a designer by training.

Campoli’s book, by contrast, is intensely visual, written in more measured prose, and filled with not only the principles but also the design details we need to create the sort of walkable city that Jeff advocates. It’s a little less about the street surfaces and a little more about the buildings that line them, the "streetscape." Though I suspect the two authors would agree with each other on 80 percent or more of their books’ content, they bring different assets to the table, and each teaches us important things that we need to know. If you take both to heart, you will learn a heck of a lot about what makes a good city. (By the way, I hope Campoli’s book gets even half the marketing push that Jeff’s enjoys.)

Made for Walking has seven chapters. The first three summarize the research and experience with respect to urban form and travel behavior. She does a great job of comparing the daily trip details of three families (I believe they are actual, not hypothetical) who live in an outer suburb, an inner suburb, and a city setting, respectively. These are well detailed and illustrated and do a great job of explaining the challenge presented by prevailing land use patterns.

Neighborhoods and travel behavior

Campoli also relies heavily on what I consider to be the definitive study of how land use affects travel, Ewing and Cervero’s epic meta-analysis of the “five Ds”: density, diversity, design, destination accessibility, and distance to transit. All are significant, especially destination accessibility (regional location) for reducing driving, and design (street network) for increasing walking. Campoli adds a “P” for parking to the list of influential factors.

(Writing that leads me to a quibble that has long preceded Campoli’s new book. I think someone tried too hard to make everything begin with the letter D and created misimpressions as a result. “Design,” for example, is a much broader word that few people – even planning nerds – would immediately associate with streets. “Distance to transit” really misses an important point of how the presence of transit affects travel choices; a transit-rich location – with good frequency of service and multiple accessible lines – will be more influential even if the nearest stop is 10 minutes away than will a stop across the street that has only hourly service.)

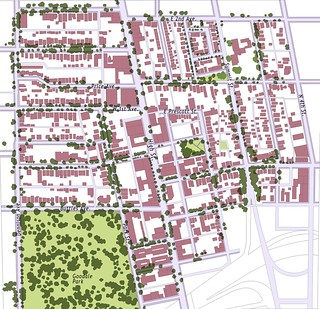

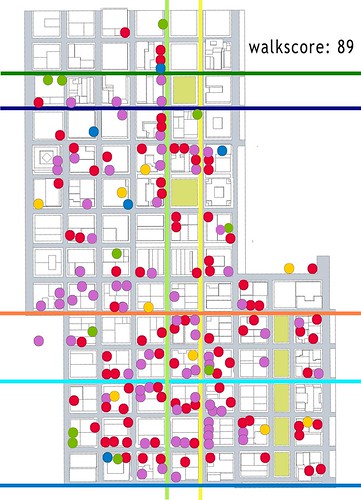

The heart of the book – comprising nearly a hundred pages – is a systematic review of twelve walkable neighborhoods in Denver, Columbus, Vancouver, Miami Beach, Toronto, Alexandria (Virginia), Albuquerque, Portland, Brooklyn, San Diego, Cambridge (Massachusetts), and Pasadena. The ones I’m showing with this article are Short North in Columbus, Kitsilano in Vancouver, Little Portugal in Toronto, and Eisenhower East in Alexandria. I’m also including a photo from the book of the multi-use recreational trail stretching along the coast from Venice Beach to Santa Monica in California. (If you’re reading this on my home site, just move your cursor over the images to tell which is which. If not, just click here to go to the home site – NRDC Switchboard – and get the details.)

For each, Campoli provides a context map, site maps illustrating neighborhood form and intersection density – the most statistically significant measure of how walkable a neighborhood is – multiple photos of the streetscape and neighborhood assets, measurements of neighborhood size, density and driving rates, and a discussion of what is going on in the neighborhood that adds to or limits its function for walking and sustainability. She likes them all, as do I.

For example, discussing Portland’s Pearl District, Campoli points out that the city has a goal of evolving a demographically mixed neighborhood, including families with children. This requires, she notes, investment in larger-unit, family-friendly homes; access to public amenities such as schools and nature; proximity to cultural resources such as libraries; and buffering from land uses that might be harmful to children. People in my environmental-group and smart-growth circles talk about this kind of thing, well, never. And yet it’s critical to a sustainable future, which is why I know about 50 people who need to read this book.

It’s about more than numbers

I really like that Made for Walking not only gives us the numbers but also stresses other important assets such as nature:

“The five Ds make neighborhoods walkable, but a host of other attributes make them livable. Some, like open space, depend on larger systems that extend well beyond the confines of a neighborhood and require big thinking, long-term planning, and broad cooperation. Neighborhood parks are essential, but greater density demands more than that. It requires many varied, high-quality green spaces – large and small, formal and wild, for active recreation and solitude – that form a network across the metropolis and to wilderness areas beyond.”

Wow – She basically linked the new environmentalism of cities to the old environmentalism of wilderness in those last two sentences. Brava. And she continues:

“Livability also depends on large systems beyond the realm of physical design. Public safety, education, affordability, and municipal services are among people’s chief concerns when deciding where to buy or rent a home. They want an affordable place in a safe neighborhood where the schools are good, the streets are swept, and the trash is picked up. If an urban neighborhood can’t satisfy these needs,

people will move to a low-density suburb to find them, even if it means spending more time and money owning and driving a car.”

I firmly believe that, if we cannot provide residents and businesses what they want and need, we will never achieve the more sustainable future for cities and suburbs that we seek. And, as I've said before, we may not deserve to.

Green revitalization

As Campoli notes, most of her twelve exemplary neighborhoods involve revitalization of once-disinvested places that left "good bones" upon which to reinvest and build for walkability. Each is centrally located within its region. While the commonality among the twelve limits the book somewhat, in my opinion sensitive revitalization is very much the first-choice way to go for improving cities.

It can be tricky to manage change, though. Many of these neighborhoods are adding a good bit of density, and to an extent changing the scale of the district’s architecture. In Cambridgeport, for example, very intense high-rise commercial development has been taking place adjacent to a historic district with a more human, lower-rise but still dense, scale. I think there is a real tension between maintaining human scale and what’s great about an existing neighborhood and adding intensity so that central places can accommodate more growth. How we resolve that tension will be critical to our long-range success.

Toward the end, Campoli includes a chapter on a greener form of urbanism, using Victoria, British Columbia’s Dockside Green as an example of an evolving neighborhood that emphasizes the reduction of resource consumption and pollution while also striving to get the walkability right. This is where those of us who are city advocates need to be in the 21st century; 1990s-style smart growth is fine, but it’s now happening anyway in a lot of places because of market forces. Leadership demands more, and so does the planet.

I visited and reviewed Dockside Green and was impressed, but also thought the new development (on a former brownfield) had a long way to go to reach its walkability aspirations.  Only the first phase had been completed as of my 2011 visit, though, and full build-out could resolve my misgivings. Its green technology achievements are nearly flawless so far.

Only the first phase had been completed as of my 2011 visit, though, and full build-out could resolve my misgivings. Its green technology achievements are nearly flawless so far.

Campoli describes how the development achieved and was helped by certification under LEED for Neighborhood Development, the rating system developed jointly by my organization (NRDC), the Congress for the New Urbanism, and the US Green Building Council, which now administers it. I get the impression that she likes LEED-ND, but Campoli also quite rightly points to some of its limitations in, say, trying to establish a nationally applicable set of density standards when what’s appropriate in Baltimore may not be in Bozeman, and vice versa.

Anything missing?

As you can tell, I really like Made for Walking. But it is also the job of a reviewer to point to a book’s limitations or weaknesses, and I’ll mention four:

- The issues of maintaining affordability and avoiding gentrification in revitalizing inner-city neighborhoods such as those in the twelve examples get short shrift. These are hugely important, however; we need to get cities right socially as well as environmentally.

- Closely related is the issue of NIMBY opposition to neighborhood intensification. Campoli writes that her twelve exemplar neighborhoods “share their wealth by welcoming new residents into recently added houses and apartments.” In response I might suggest that the author spend a bit more time in inner-city DC and many other places I can think of. My experience is that, while existing residents frequently are accepting of new development once it’s built and they see some of the benefits that come with it, they are anything but “welcoming” at the beginning. In would be informative to know how the twelve dealt with or avoided these conflicts.

- Picking up on Campoli’s observation contrasting Baltimore and Bozeman, I would have liked seeing some examples of how her ideas work in Bozeman-sized cities and smaller metro areas. If there is a difference as to what’s appropriate in those two, how does it play out in successful neighborhoods in each? (Apart from this particular book, I would also enjoy seeing an essay comparing the very successful places described in Made for Walking with the fading ones in Sandy Sorlien’s book-in-progress on Main Streets, The Heart of Town.)

- Finally, at $50 per copy, the book is priced so that the people I most want to read it, citizen- and nonprofit-advocates, won't have the budget to purchase it. That is really, really unfortunate.

Steven Wright

Really, though, this book is so good, and must have required so much work, that I feel a bit sheepish at pointing out that it could have covered even more territory than it did. There’s already a lot more in it than I have space to cover here, such as Campoli’s “green transportation hierarchy,” how residential garages can be subtly made to interfere less with walkable streets, and a chapter on market forces. She even quotes the great Steven Wright for a characteristically wry observation that you’ll have to find and read for yourself.

If there’s one thing I liked best, it’s the degree to which Campoli lets her images tell the story. I am majorly impressed that they are all hers and, as I said above, I would probably get the book even if it were only a book of city photos. She should do a photography exhibit at the National Building Museum, and I just may start a little campaign to make that happen.

Related posts:

- The disturbing and sometimes tragic challenge of walking in America (January 16, 2013)

- How retrofitting a California suburb for walkability is spurring economic development (January 4, 2013)

- The definitive study of how land use affects travel behavior (June 4, 2010)

- The ten steps of walkability (December 3, 2012)

- How far will we walk to go somewhere? It depends. (July 30, 2012)

- Data summaries show walkable communities are good for our health, and for business, too (April 13, 2012)

- Blog post number 1000: A gallery of walkability (January 30, 2012)

- More walkable urban development is good. But is it good enough? (January 18, 2012)

- Mapping a walkable lifestyle - the web of daily life (September 22, 2010)

- A local lesson in transit orientation, walkability and supermarket economics (March 8, 2010)

Move your cursor over the images for credit information.